Twenty years ago this week I jumped on a plane and headed for Florida, destination Daytona International Speedway, It was the first phase in what I now laughingly refer to as a career in motorsport. Since the early ’80s I had combined a real paying job with the weekend vice of shooting races as a member of the media. I had witnessed the final stages of Ayrton Senna’s pre-F1 career, watched with awe as Group C flowered and was eventually destroyed by dark forces and followed the re-birth of endurance racing in the ’90s. I was hooked.

Now it was time to leave behind the comfortable existence of a monthly salary, an chunky bonus most years, and a new BMW 7 or 8 series every four to six months. I was going to be a full time motorsport photographer following in the footsteps of those guys I knew in F1 who had made it to the Majors. They were doing very well, better than me or so they would have you believe. What they did not tell me was the the bit about the pain and penury, the uncertainty of where the next job or cheque would come from and the sheer grind of endless travelling for a living. All this while trying to keep clients, a bank manager, and the wife, happy.

No matter, I was gung-ho on my way to Daytona. My flight and a fee were being paid for by the charming Laurence Pearce of Lister Cars fame, it was always going to be like this I told myself…………roaming the planet on someone else’s dollar, creating art………Terry Donovan eat your heart out………..

I had shot in the USA the previous year when following the FIA GT circus to Sebring and Laguna Seca, now I was about to find out how things were really done in America.

The 1998 Rolex 24 was a race run in a time of great upheaval and transition, both on and off the track. On a broader scale the world was shifting on its axis from analogue to digital, the new-fangled internet and email was here to stay, and old farts like me would have to get used to it, embrace it even, Dot-Com was the buzz word on everyone’s lips. A new century beckoned and a totally unjustified optimism was all around, as if we had all bought into Donald Fagan’s vision:

A just machine to make big decisions,

Programmed by fellows with compassion and vision,

We’ll be clean when their work is done,

We’ll be eternally free, yes, and eternally young

On the tracks the world was also going through a revolution, especially in the rarefied arena of endurance racing in North America. In the post-Andy Evans era, Daytona in 1998 was the first battleground in the looming conflict between the traditional powers, aka the France family, and the new broom, Don Panoz, controller of three tracks, and his plans for sportscar racing in North America that would evolve into the American Le Mans Series. We all know how that turned out in the end.

For a foot-soldier such as I this all seemed remote, all I could see was the beautiful Florida sunshine, a real contrast to the grey, soggy conditions back home. At the track there was the amazing banking, there were also a lot of fences and gates to negotiate and even more security guards to deal with, all dressed in blue, some armed, seemingly with an agenda all of their own.

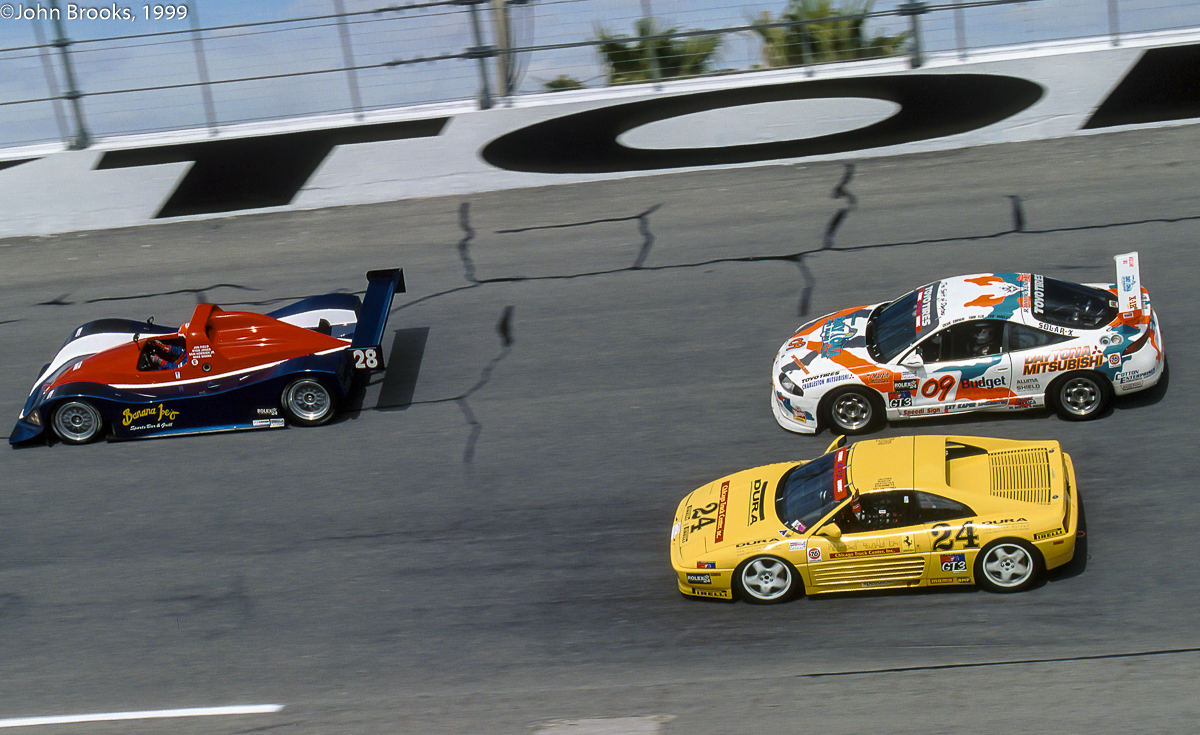

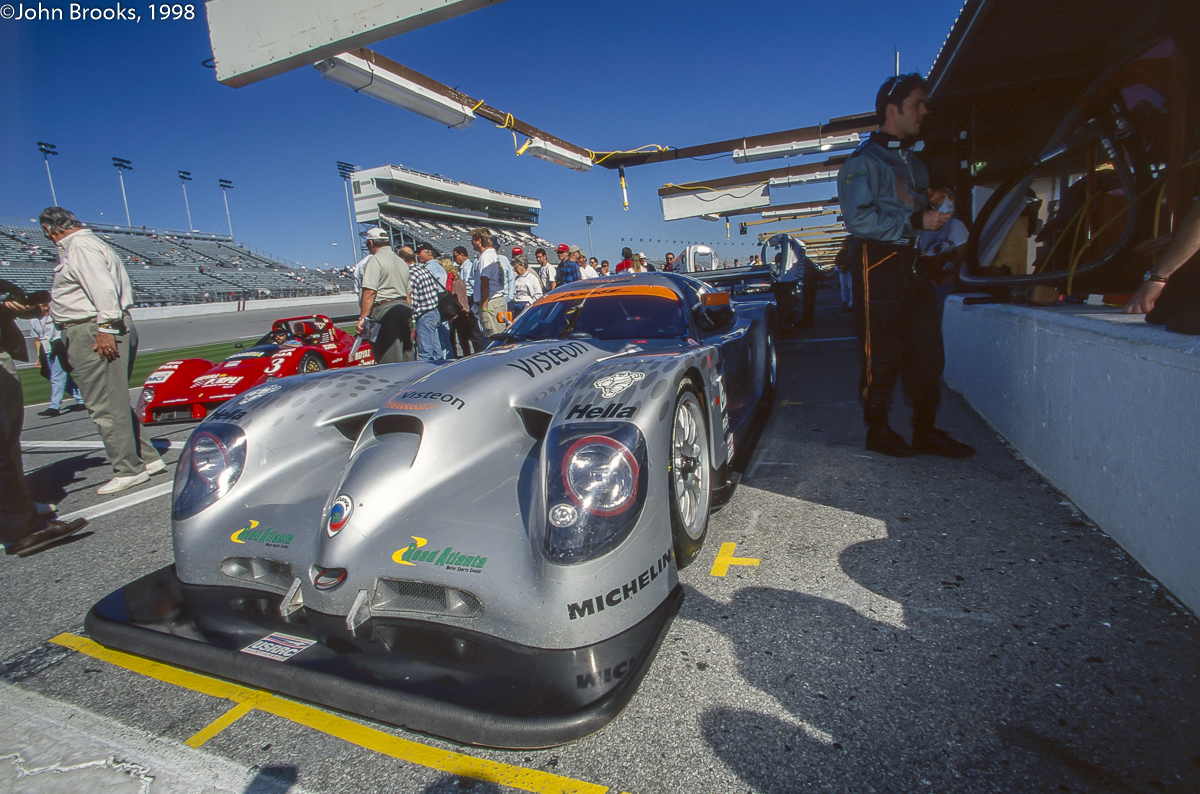

On track the cars were something of a throwback, the favourites for victory came from the various Ferrari 333 SP teams or the Ford-powered Dyson Racing Riley & Scott MKIII pair. These fine cars would have been nowhere if faced by the top practitioners in Europe, such as the Mercedes-Benz CLK LM or the Toyota GT-One, who were in a different league of performance and, of course, budget.

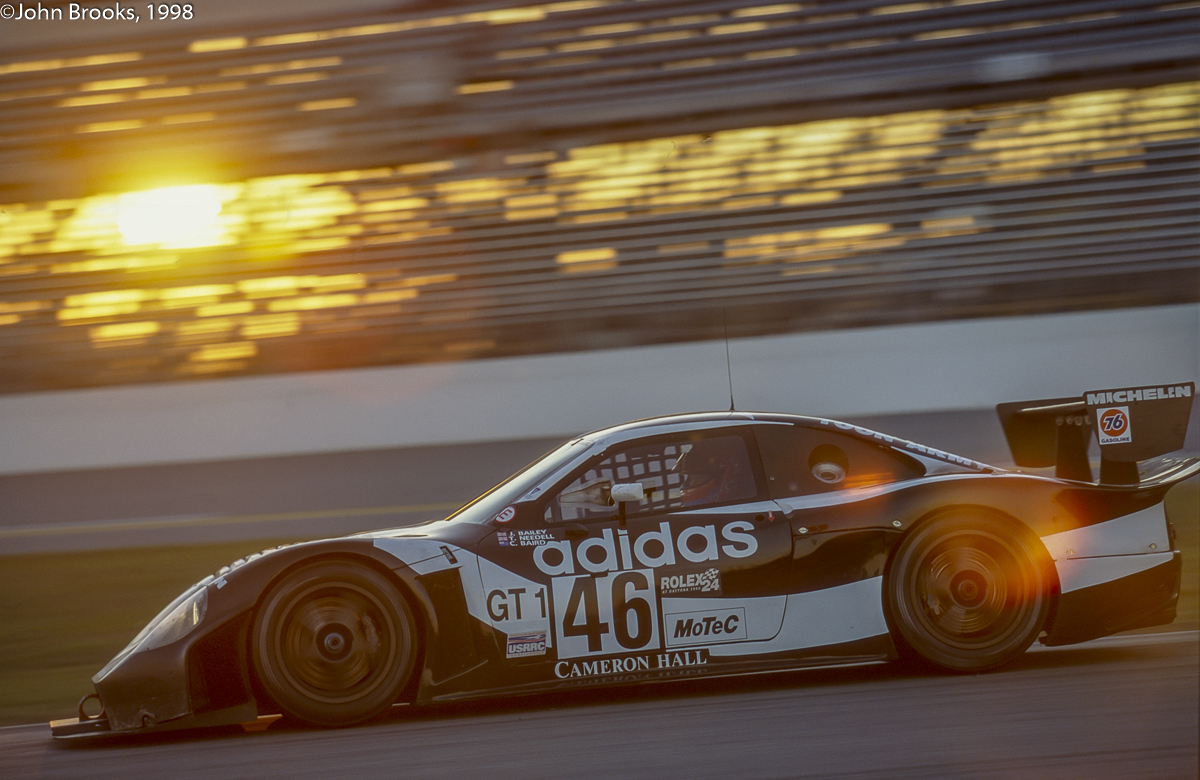

Indeed from the European scene three Porsche 911 GT1s, a brace of Panoz GTR-1s and a Lister Storm GTL were on the Rolex 24 GT1 entry list creating a problem for the local officials who wished for the top step of the podium to be the property of the prototype class, cunningly renamed CanAm. What relationship these cars had with the Group 7 legends of yesteryear was unclear but it made the PR guys feel warm and everyone pretended that it was absolutely logical.

Another PR canard doing the rounds at the race was the insistence that the 1998 Rolex 24 would be a re-run of the Ford v Ferrari battles of the ’60s, Phil Space and his mates in the old press rooms would have been proud. Like the CanAm non-connection no one was fooled but we were all too polite to mention it.

Perhaps the whole paddock that year would have wanted to see Gianpiero “Momo” Moretti finally achieve a win at Daytona. He had first raced the 24 Hours at the tri-oval in the 1970 edition driving a Ferrari 512S no less. Twenty-eight years and fourteen attempts later he knew that time was against him, but 1998 was as good an opportunity as ever. As Momo put it at the time, “With all the money I have spent at Daytona I could have bought a thousand Rolexes easily, but I wanted to win this race.”

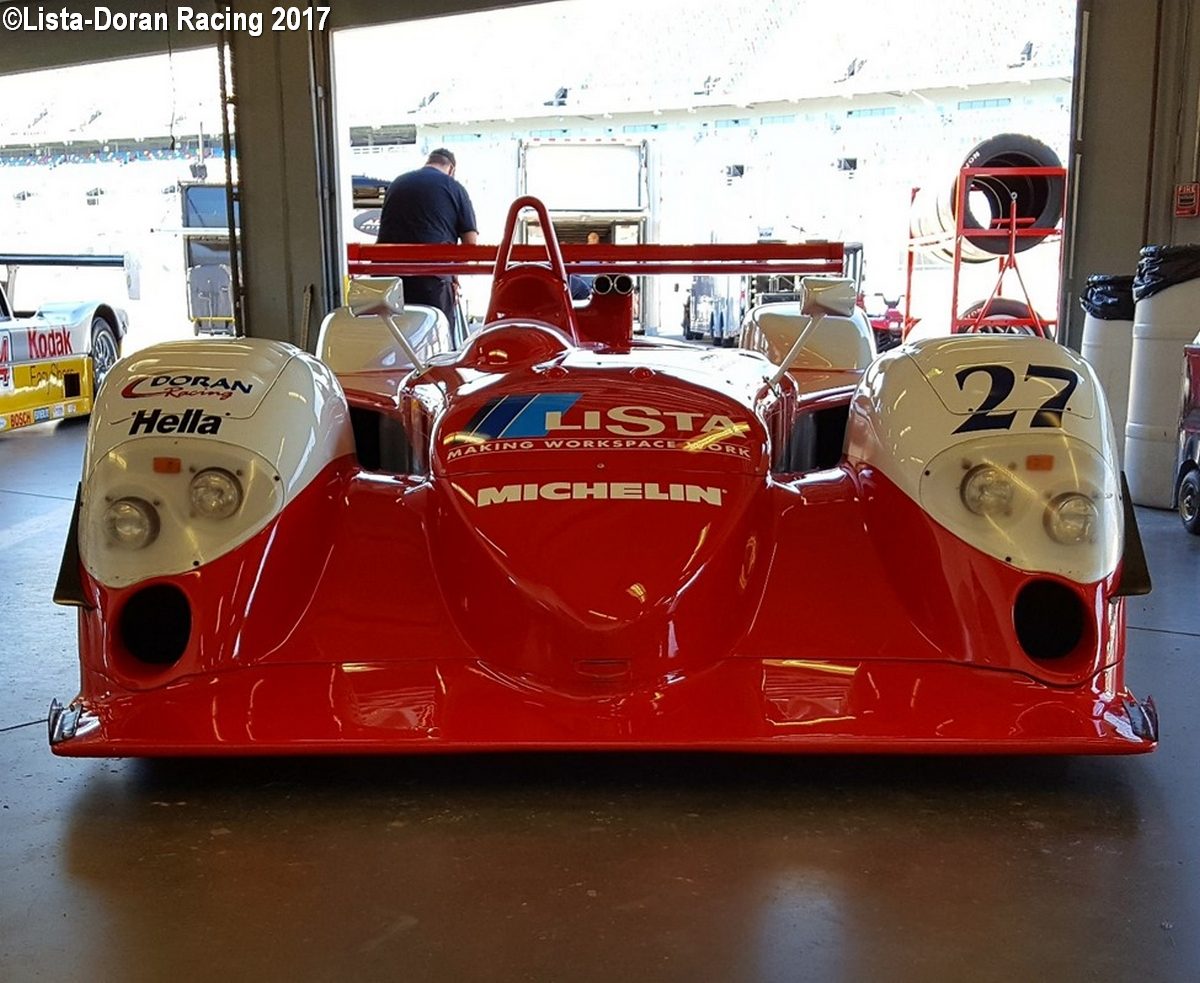

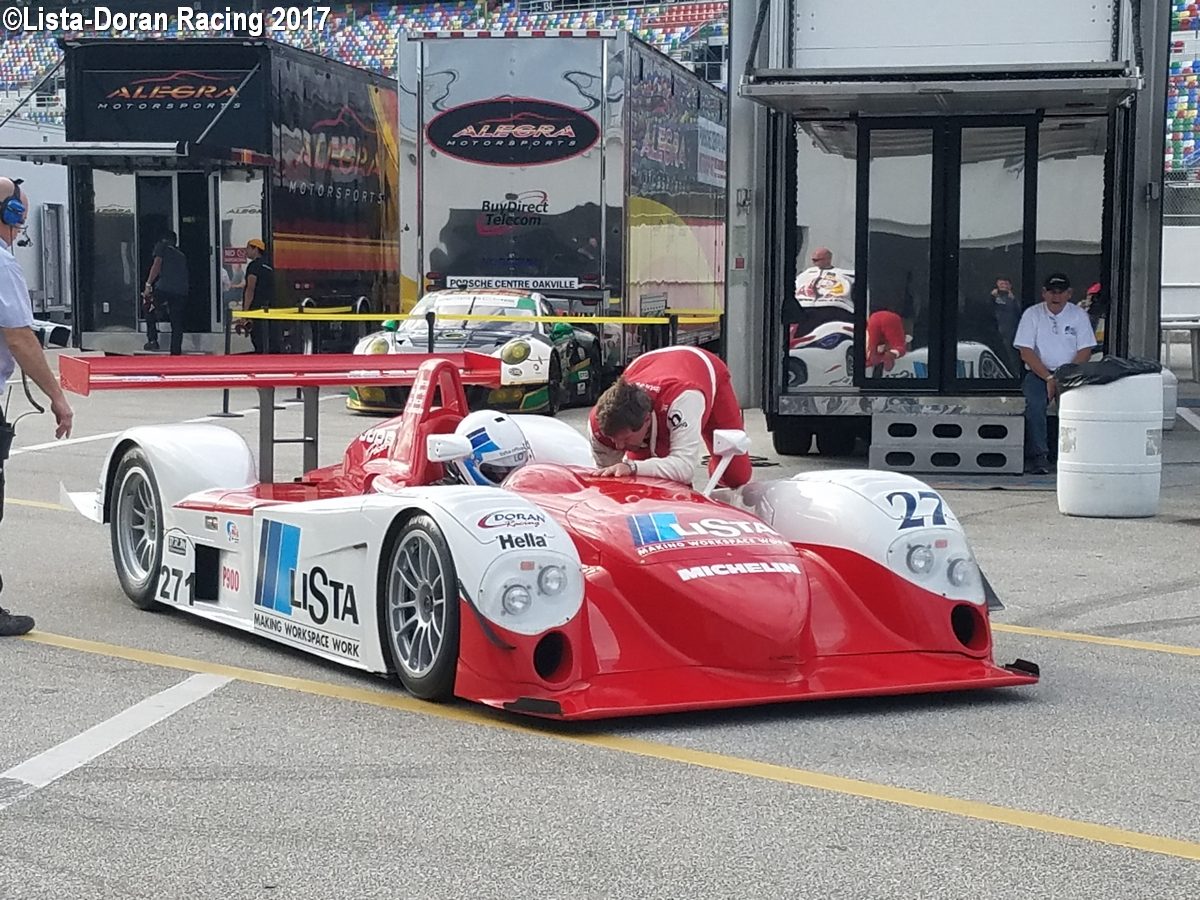

His Ferrari 333 SP was run by the vastly experienced Kevin Doran and he had a stellar line-up with Mauro Baldi, Arie Luyendyk and Didier Theys, it was now or never.

Joining Momo on the grid, though a few rows back was another driver who had raced in the 1970 Daytona 24 Hours, Brian Redman. Back then Redman was a key part of the JW Automotive squad and the 1970 race was eagerly anticipated as it would see the first full contest between the Porsche 917s and Ferrari 512s. Brian achieved the bizarre feat of finishing both first and second in that race as he drove the winning car of Pedro Rodriguez and Leo Kinnunen for a couple of stints while waiting for his own 917 to have its clutch replaced. The Finn was placed on the naughty step for ignoring team orders to slow down while enjoying a huge lead, his punishment was to witness Redman pounding round in his car.

In 1998 Redman joined 1990 Le Mans winner, Price Cobb, in a Porsche 993 Carrera RSR but there would be no fairytale for the veteran Brit, a broken gearbox on Saturday brought his career in 24-hour races to an end.

Opposition in CanAm Ferrari ranks came principally from the Scandia Engineering example crewed by Yannick Dalmas, Bob Wollek Max Papis and Ron Fellows. Dalmas took pole with a 1:39.195 lap, just shy of 130 mph average speed, this was a serious effort at winning outright.

Doyle-Risi Racing had left their 1996 Daytona-winning Oldsmobile-powered Riley & Scott behind in favour of a 333 SP, backing up Wayne Taylor behind the wheel were Fermin Velez and Eric van de Poele, another serious candidate for overall victory.

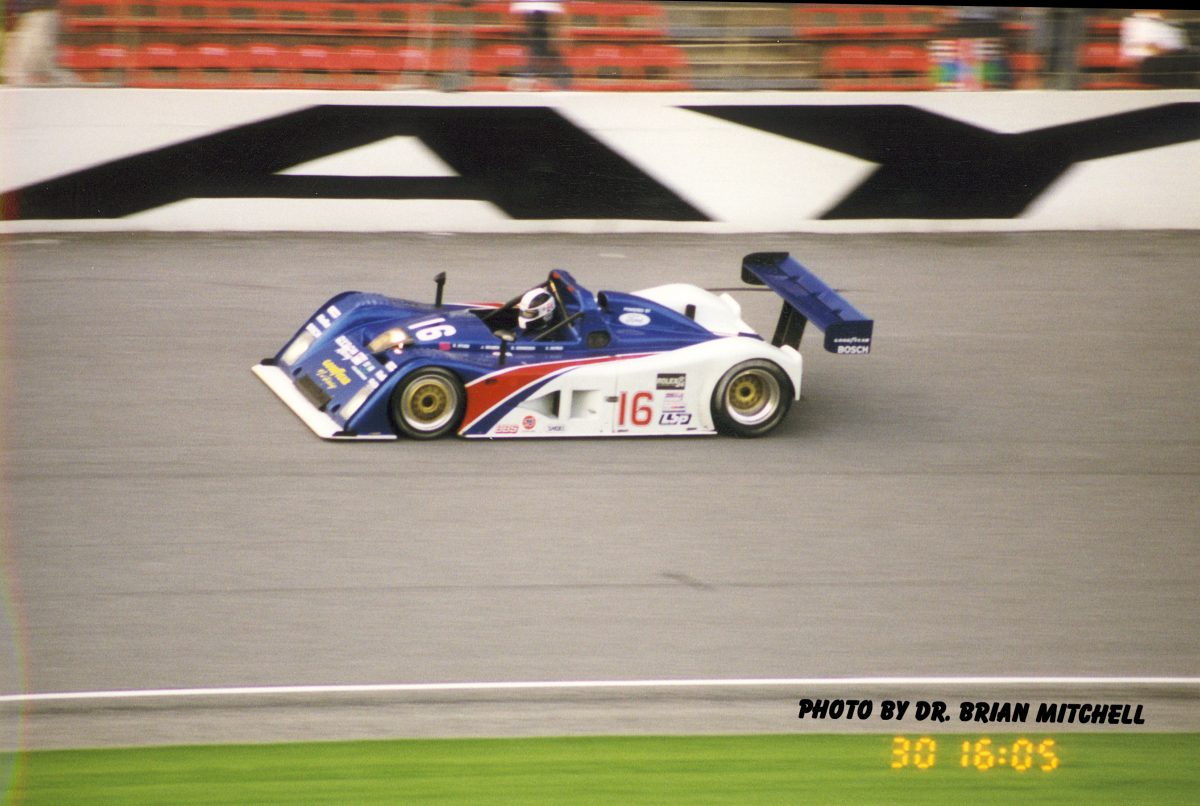

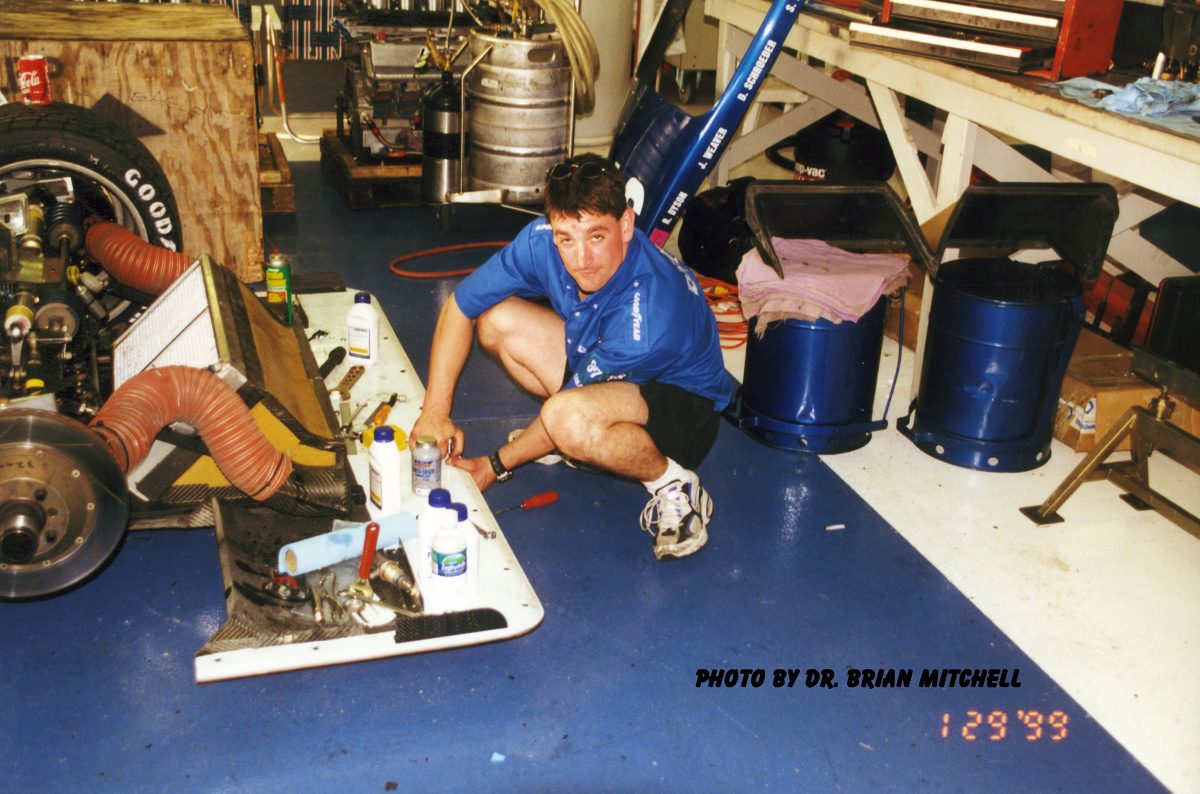

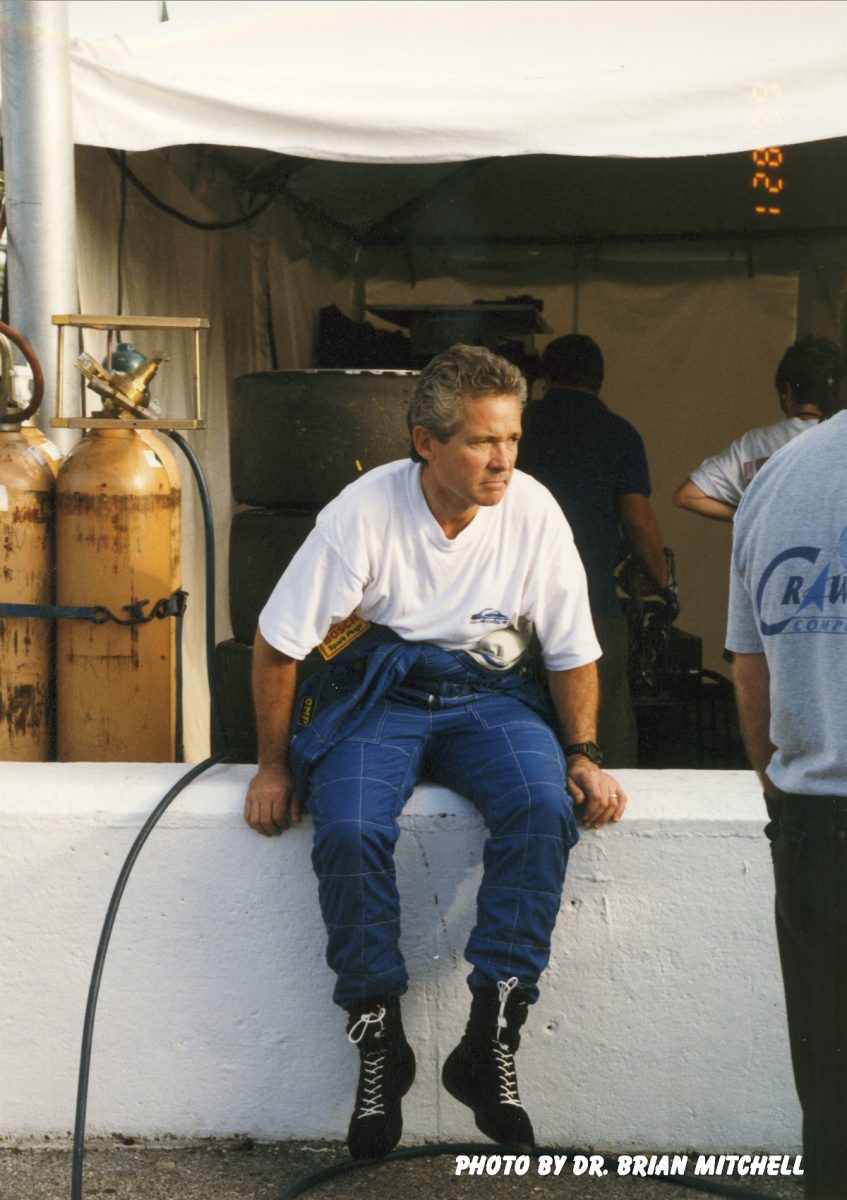

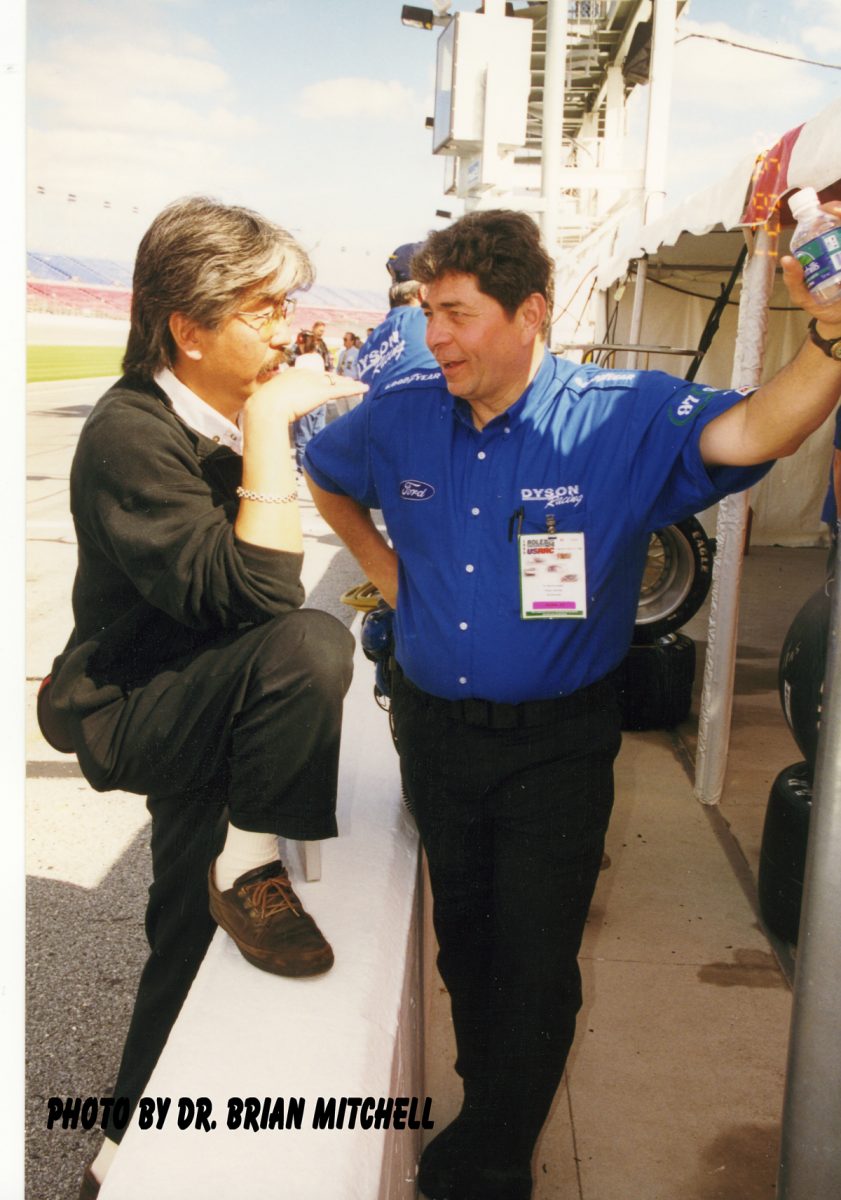

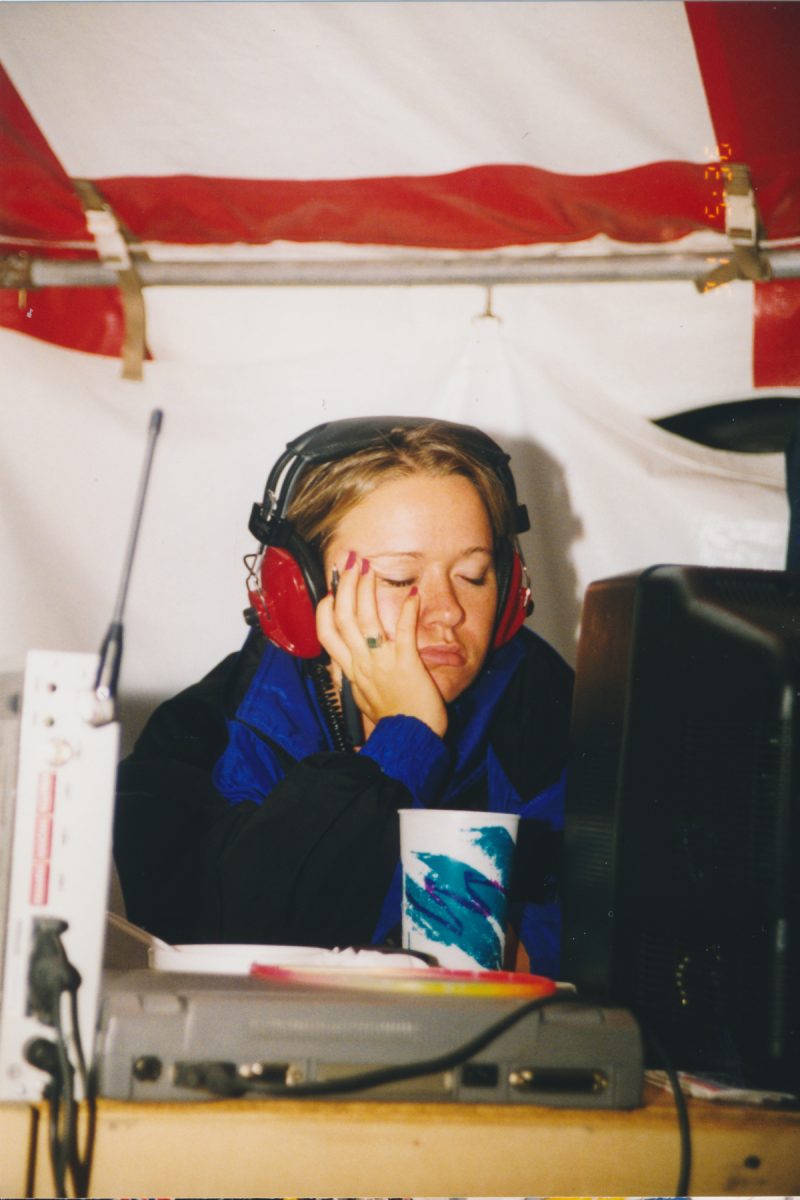

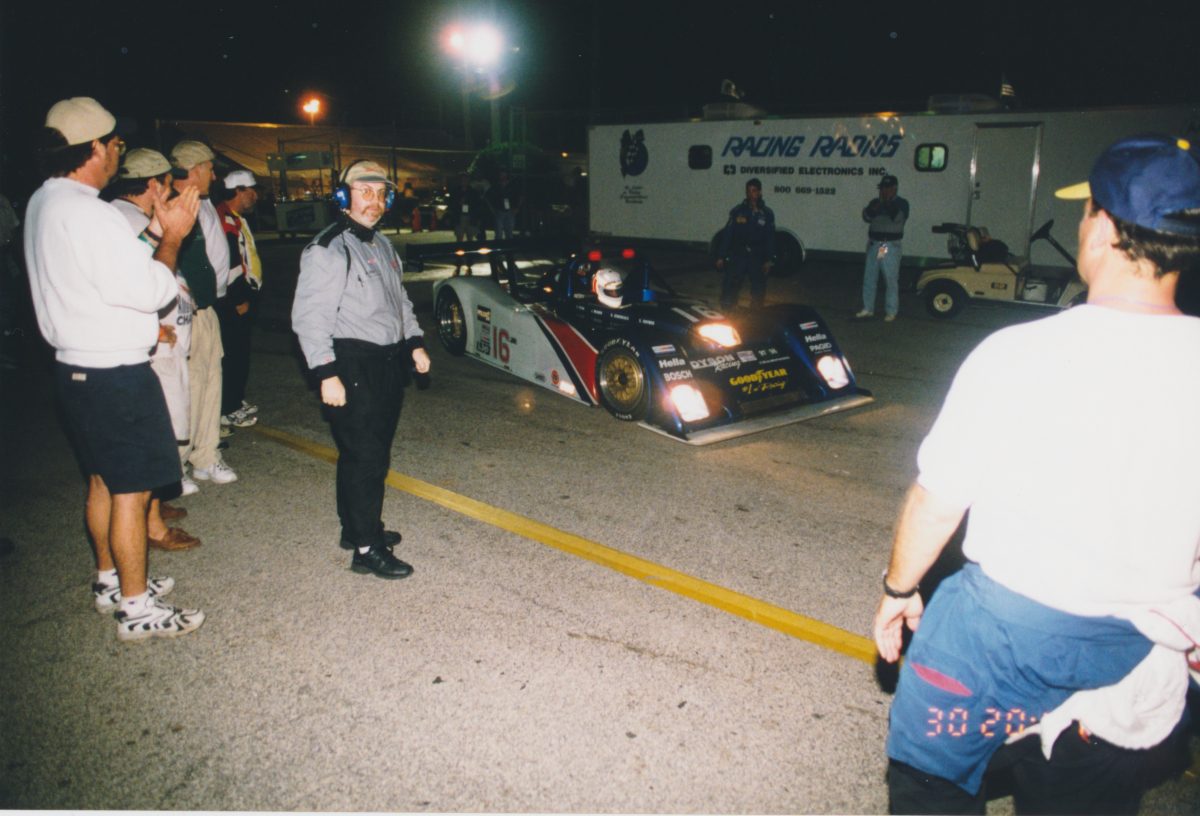

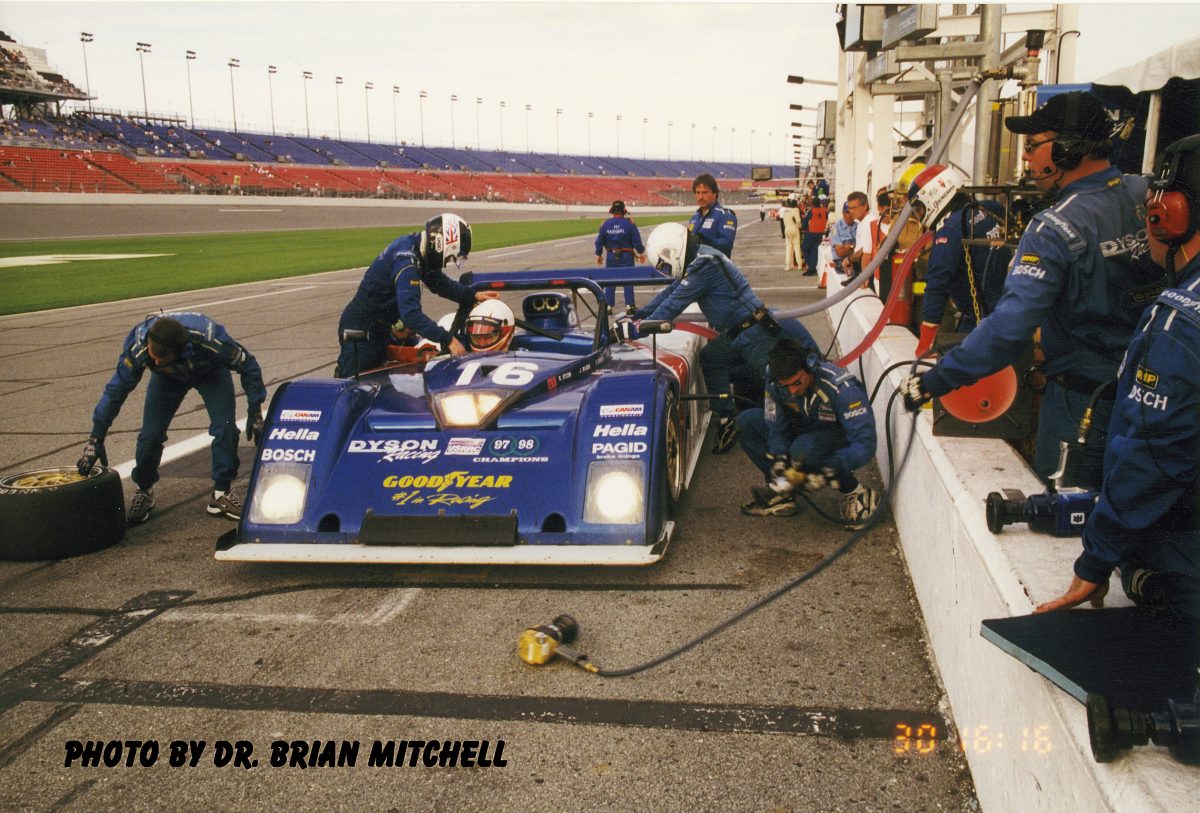

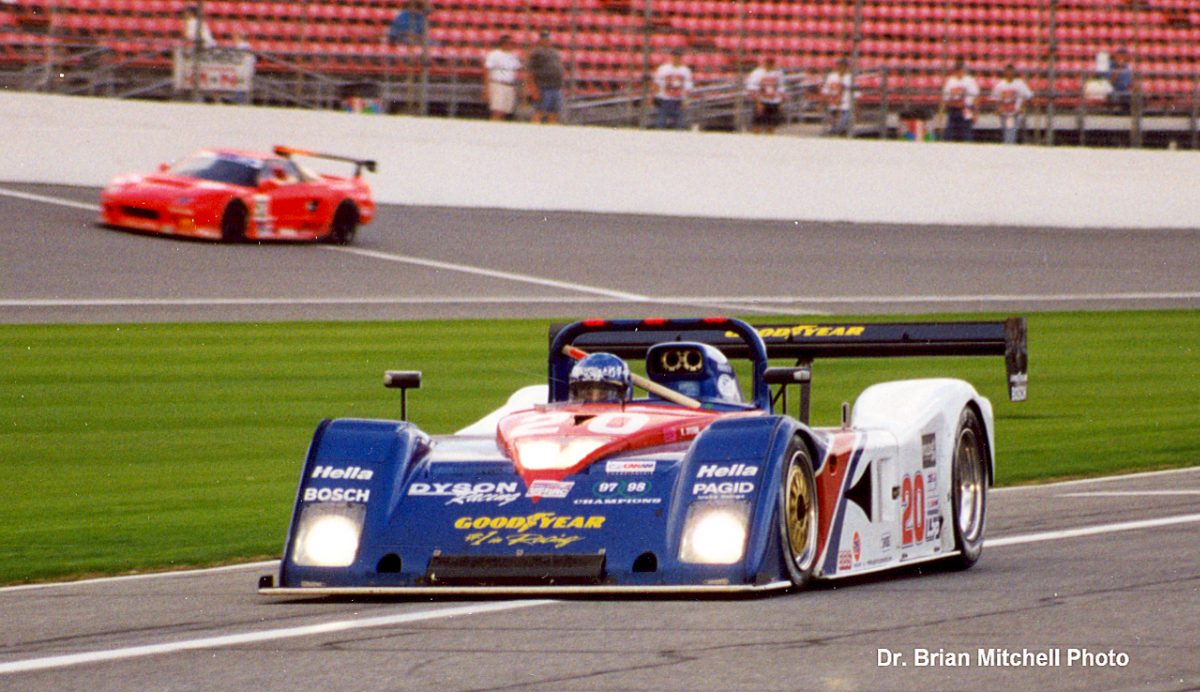

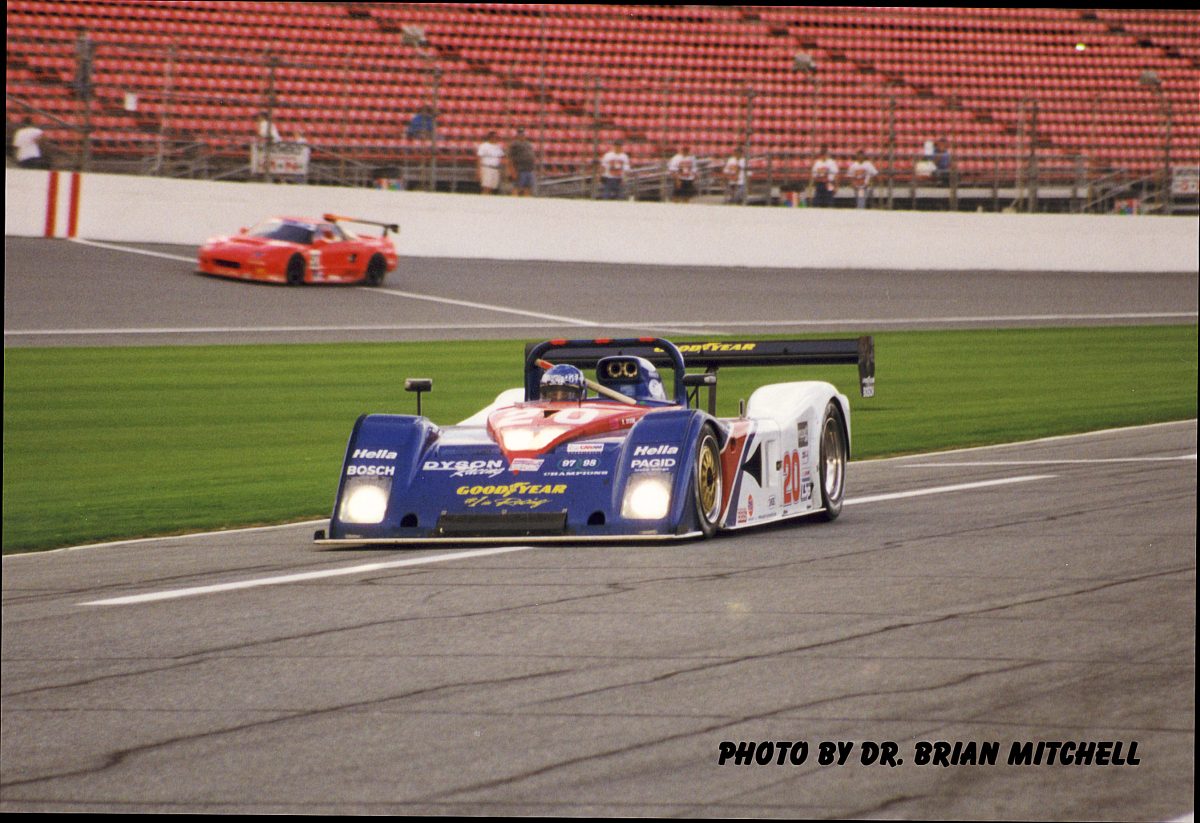

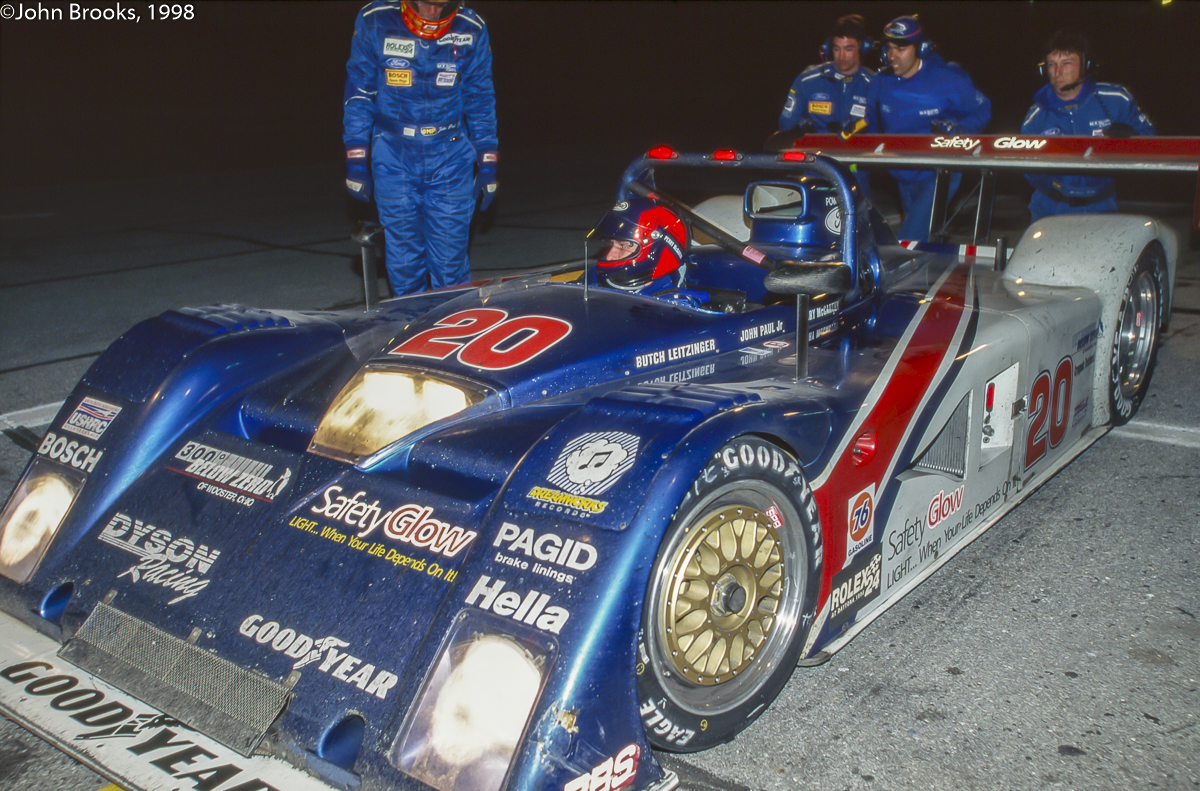

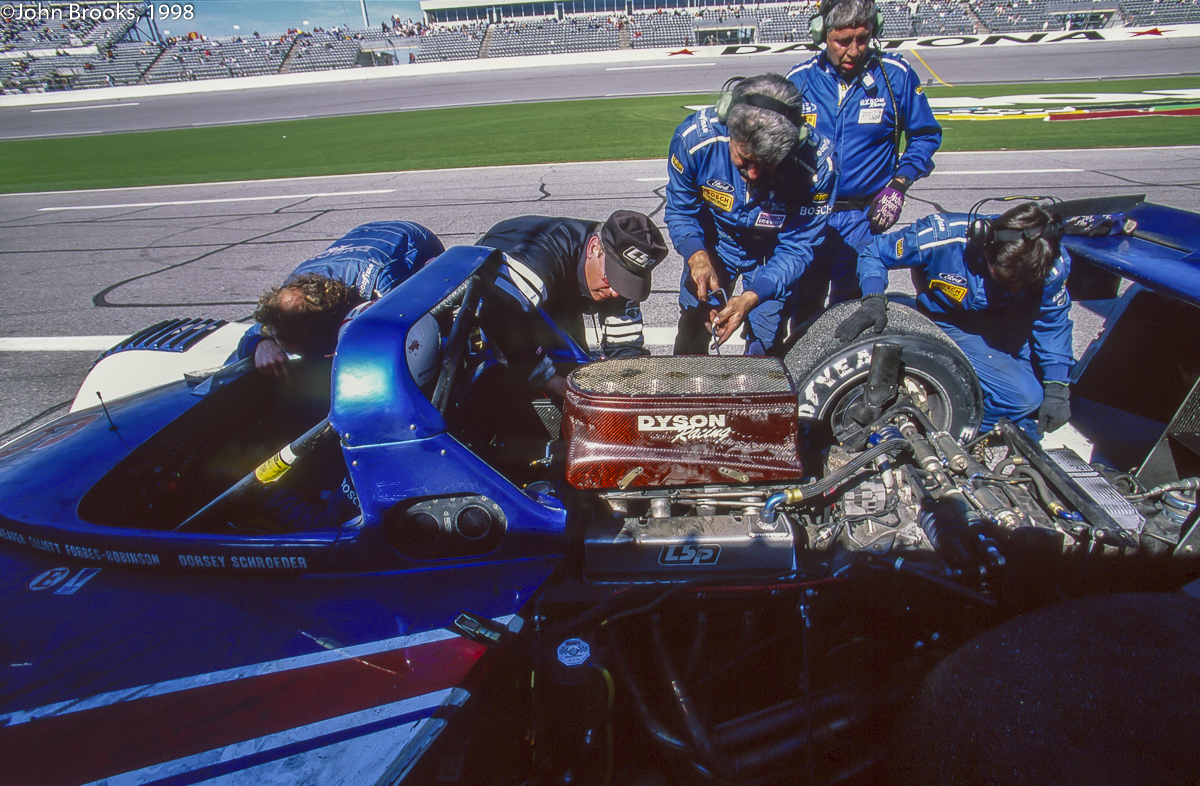

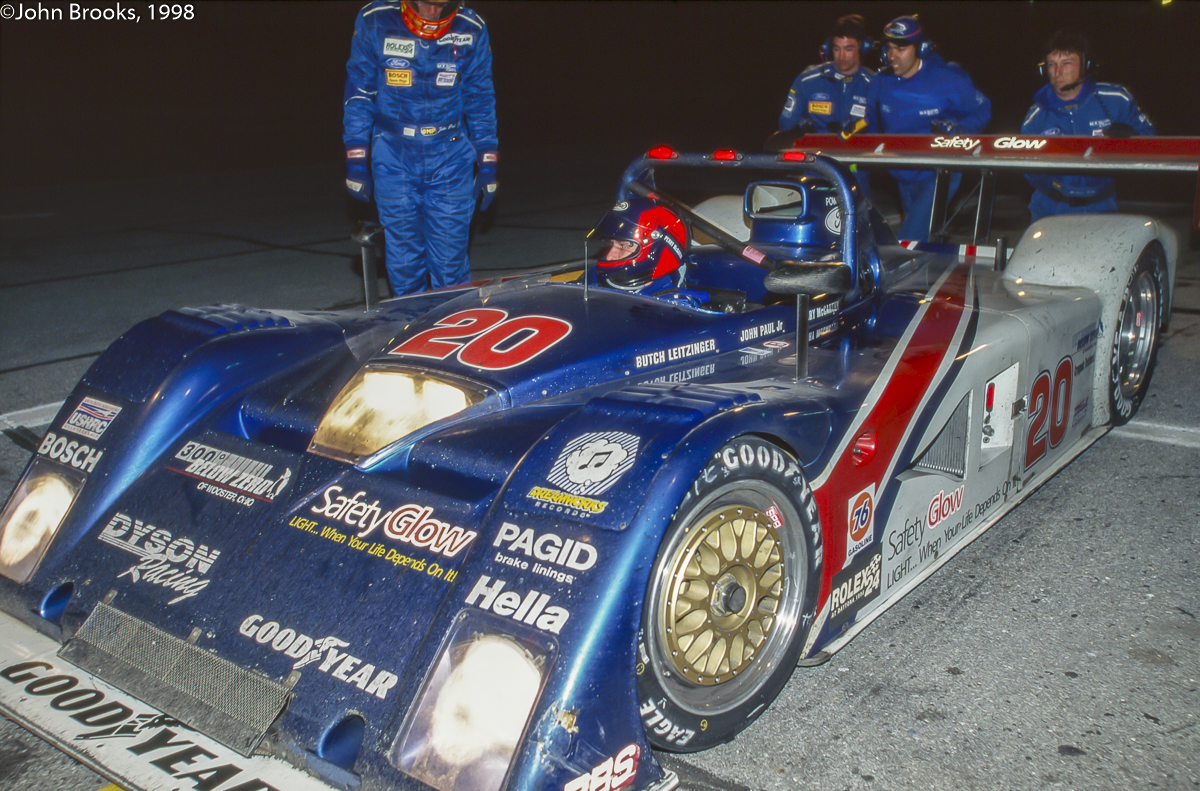

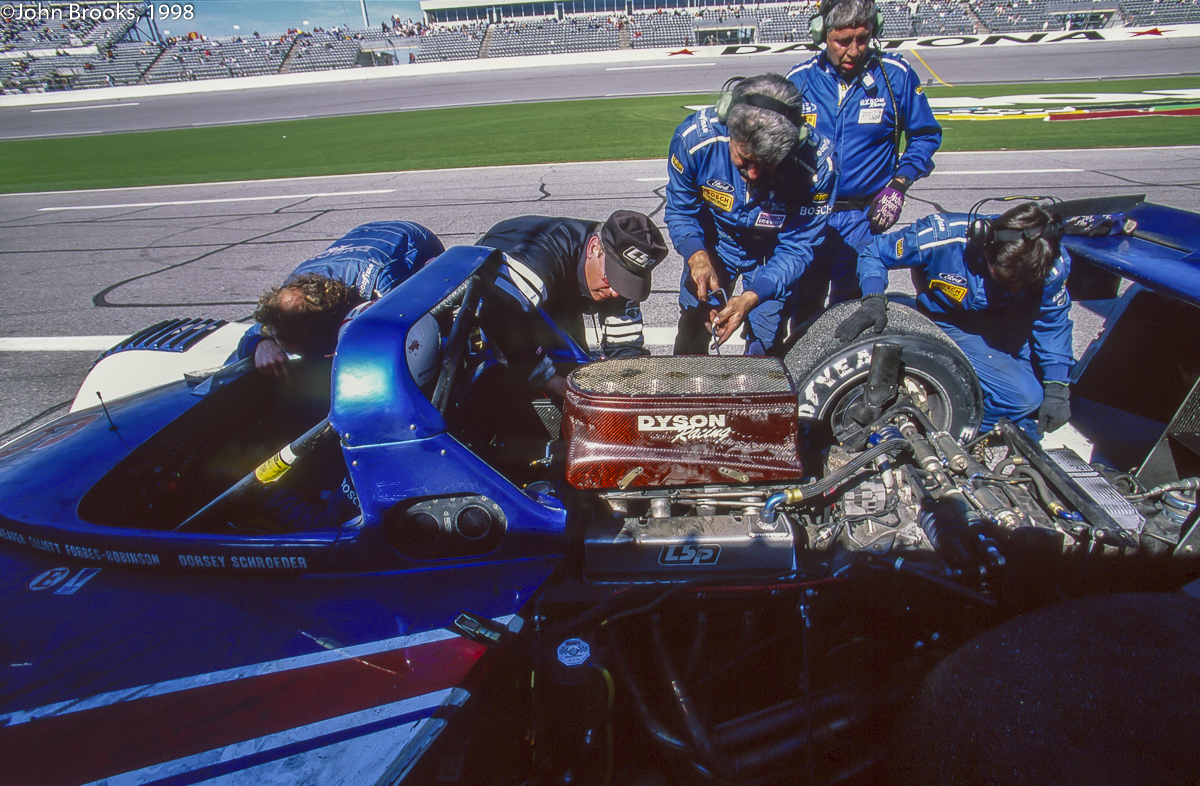

There were arguably five serious Riley & Scott contenders, all Ford powered. Two from Rob Dyson’s crack outfit based at Poughkeepsie. #16 for James Weaver, Elliot Forbes-Robinson and Dorsey Schroeder as well as the Guv’nor, seen here at the wheel.

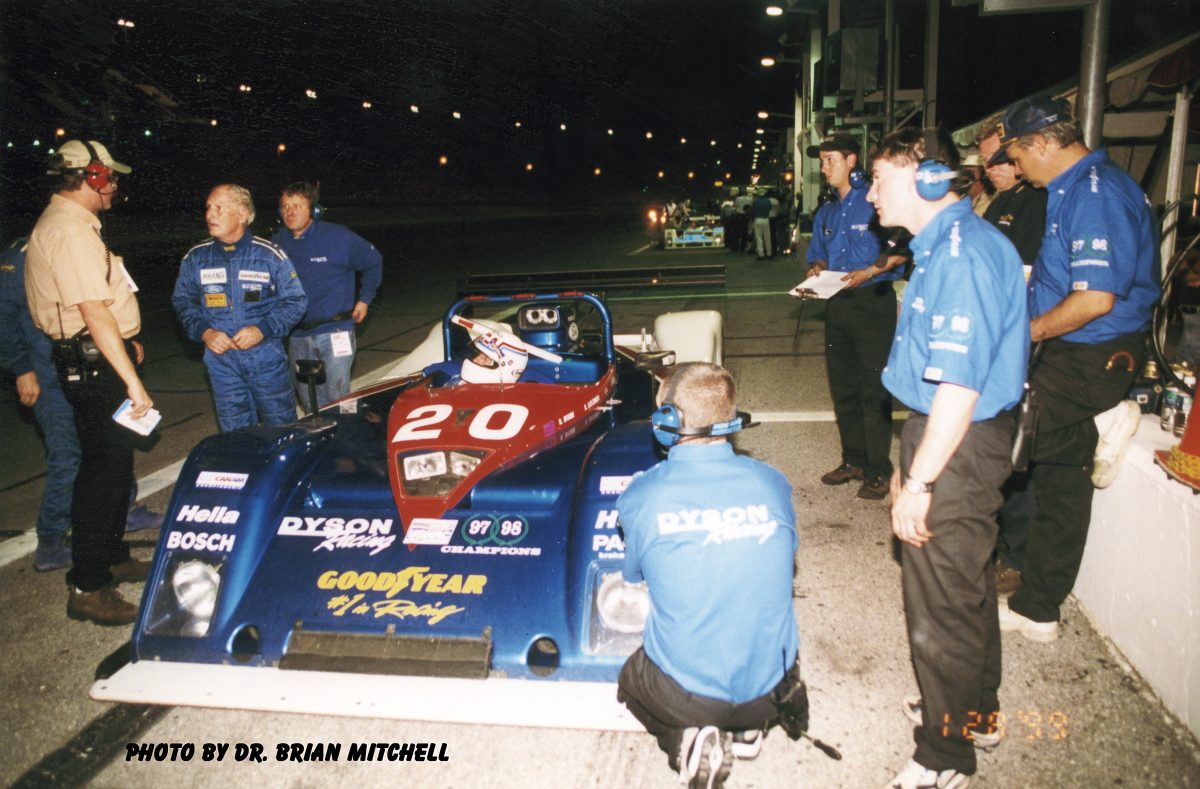

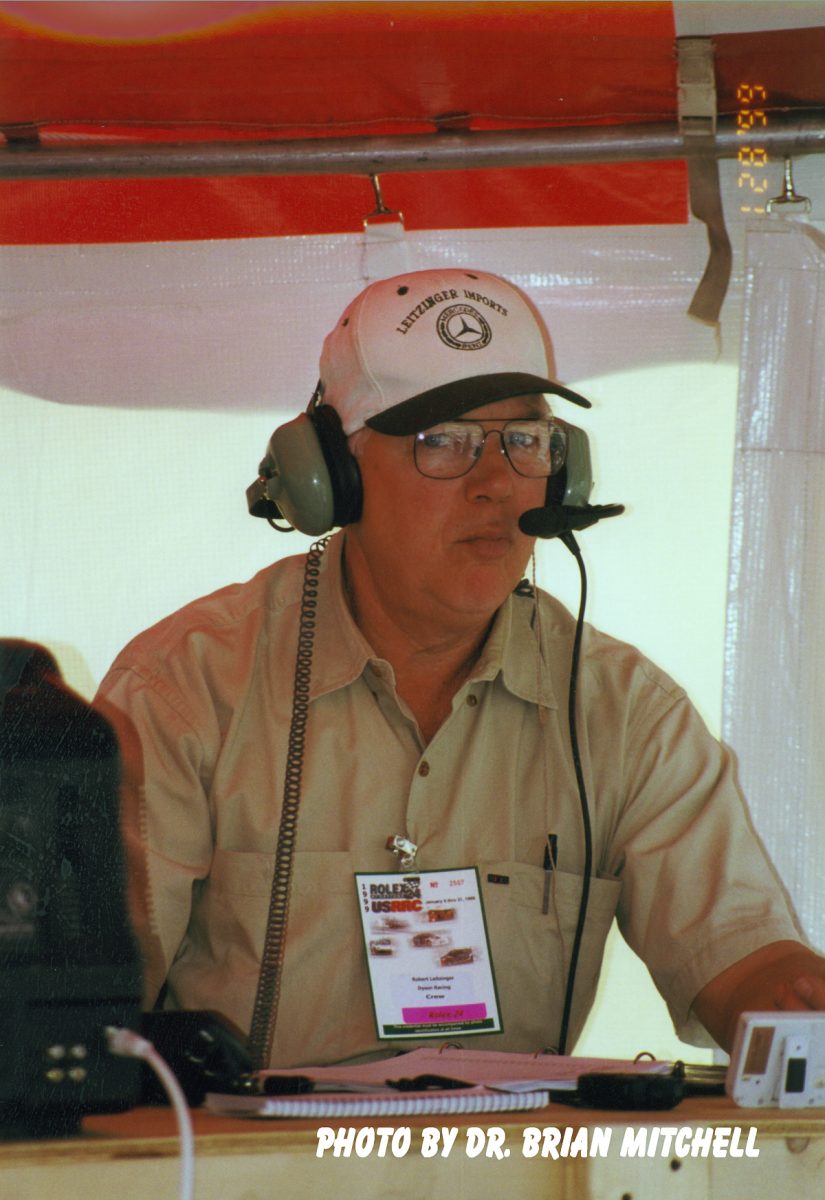

In #20 Rob was joined by Butch Leitzinger, John Paul Jr., and Perry McCarthy. Rob was keen to repeat his Daytona triumph of the previous year, his cars were always in contention down in Florida, in 1998 they started from 4th and 5th places.

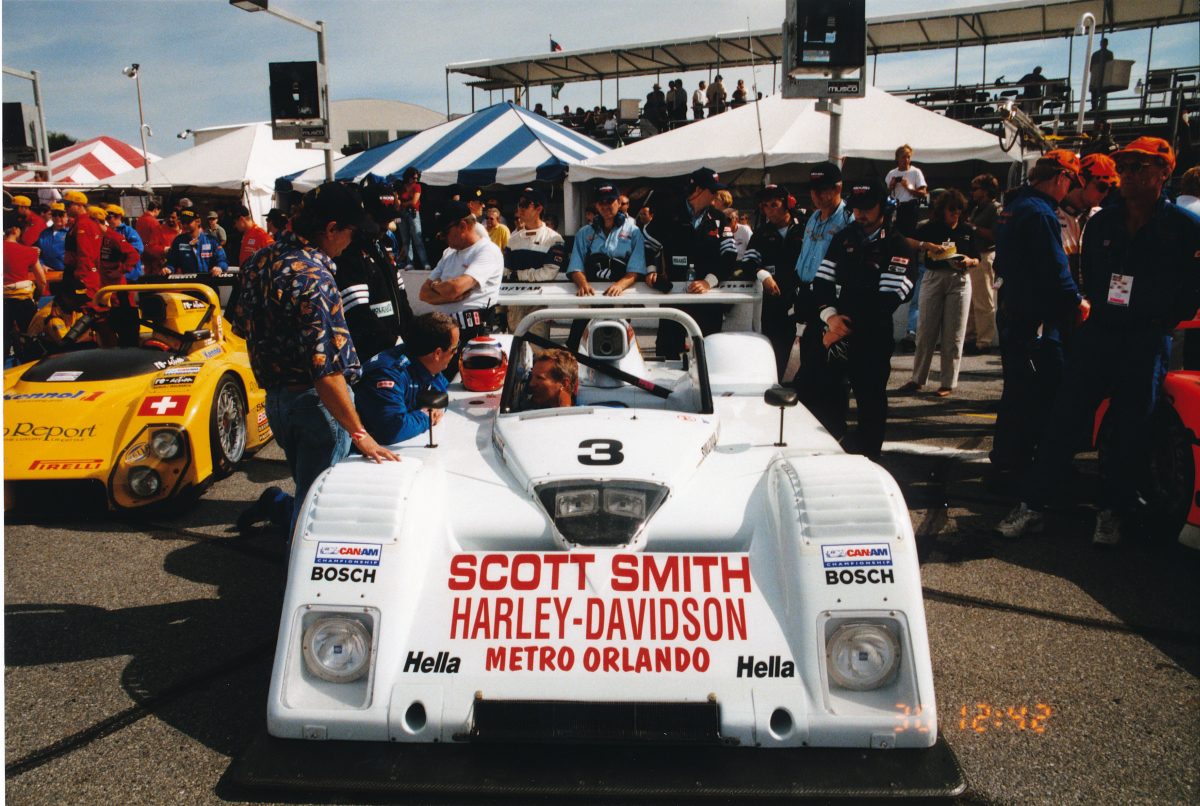

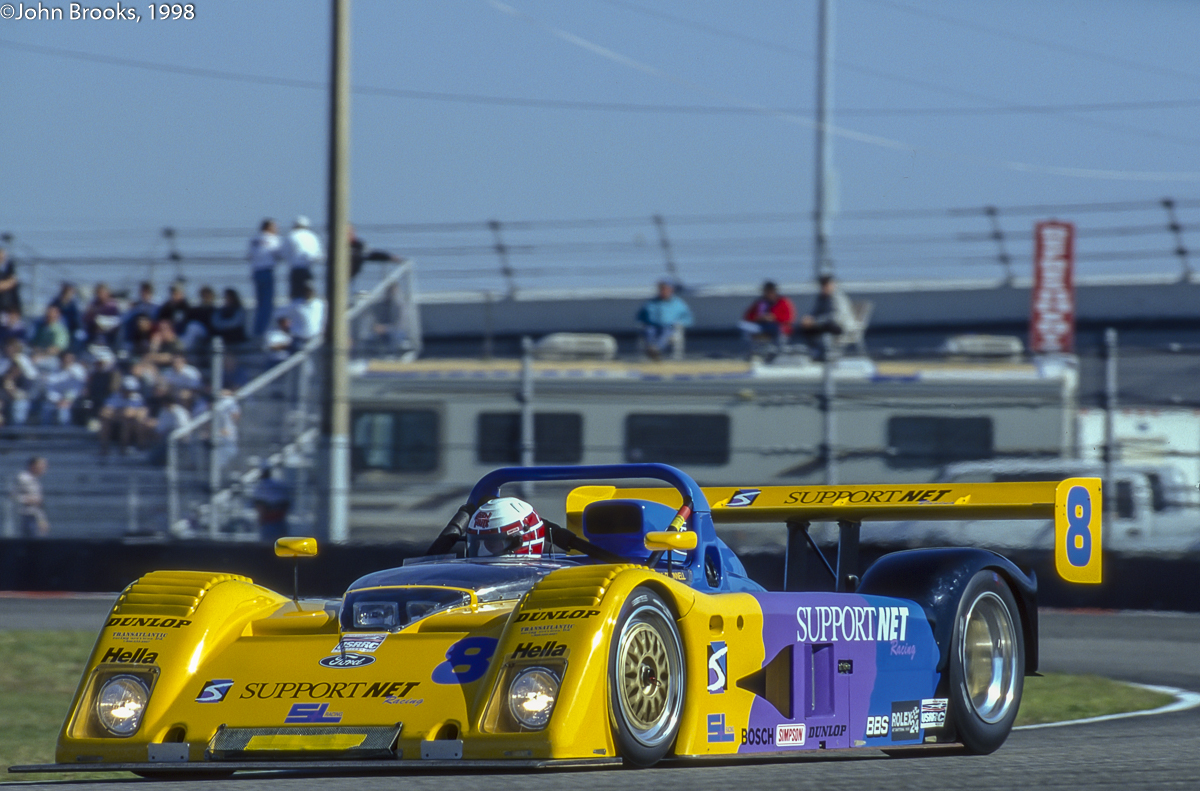

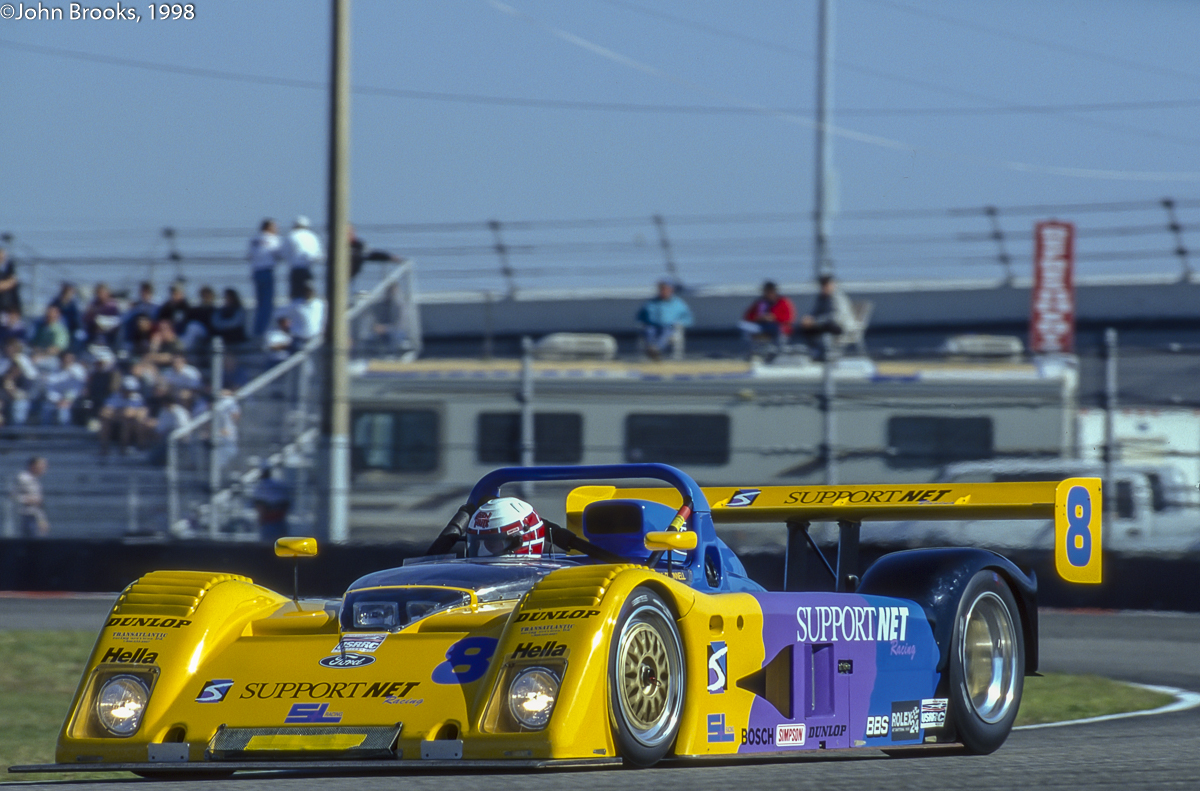

Henry Camferdam enlisted Scott Schubot and Johnny O’Connell in his R & S MKIII, they started at a respectable sixth spot.

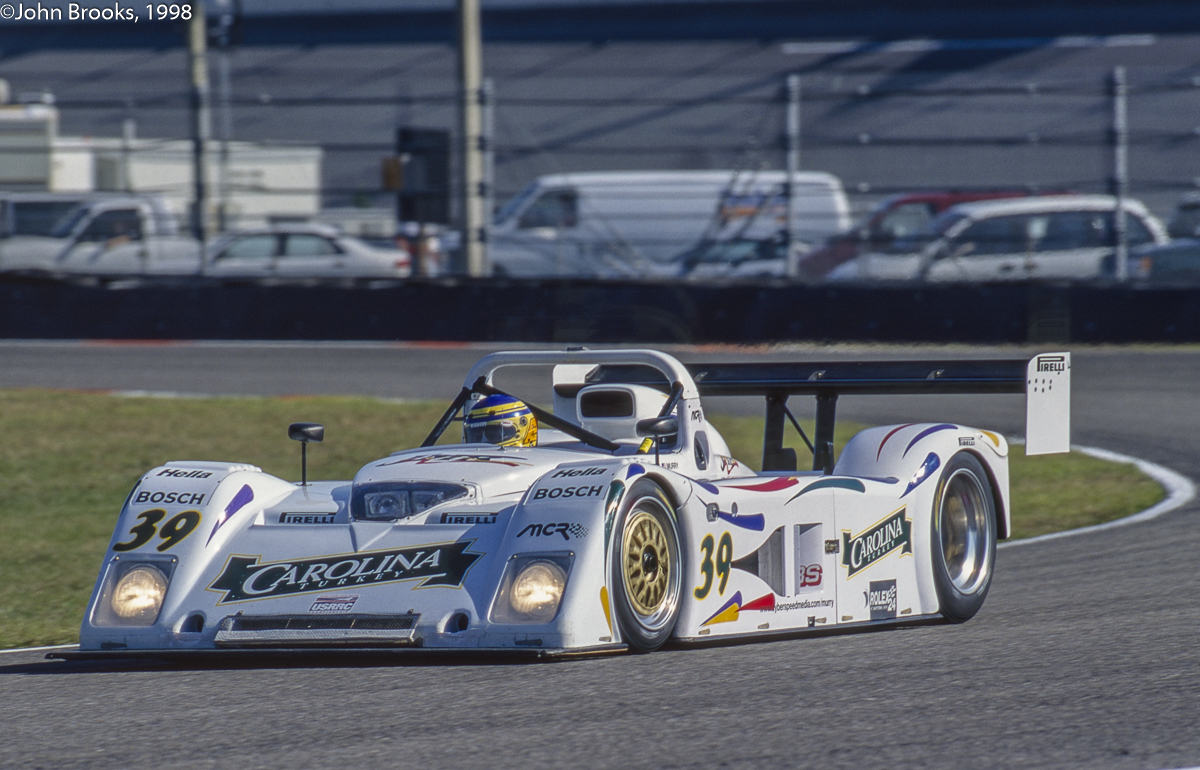

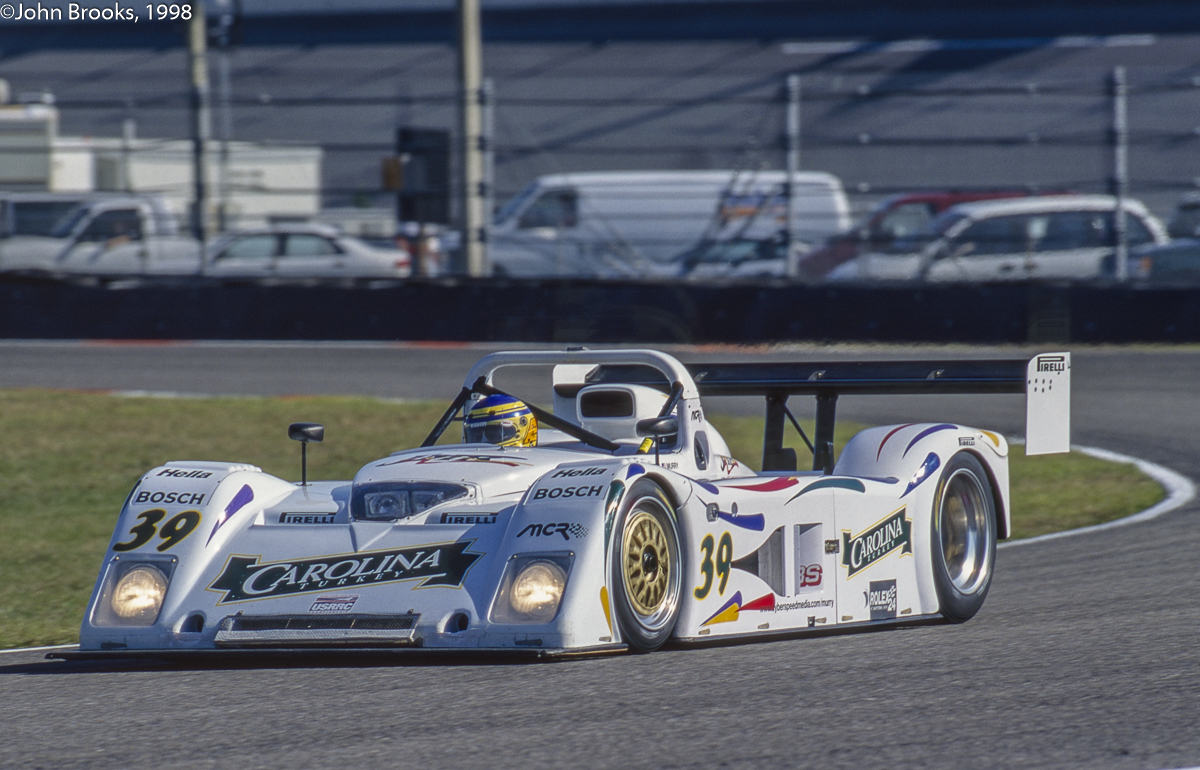

Michael Colucci ran a pair of Rileys in association with turkey-magnate Jim Matthews. Matthews was partnered in #39 by the ‘dream team’ of multiple champions Derek Bell and Hurley Haywood, plus David Murry.

#36 had Eliseo Salazar, Jim Pace and Barry Waddell on driving duty with Matthews hedging his bets as an entry in both cars.

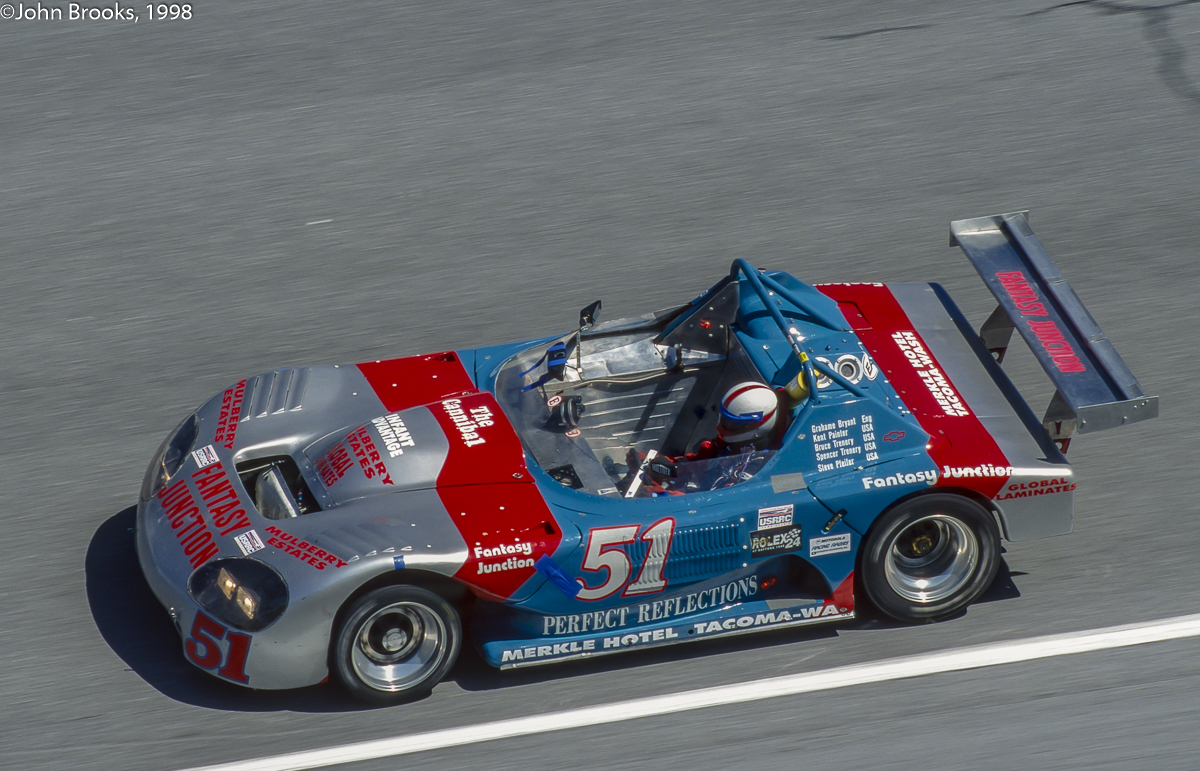

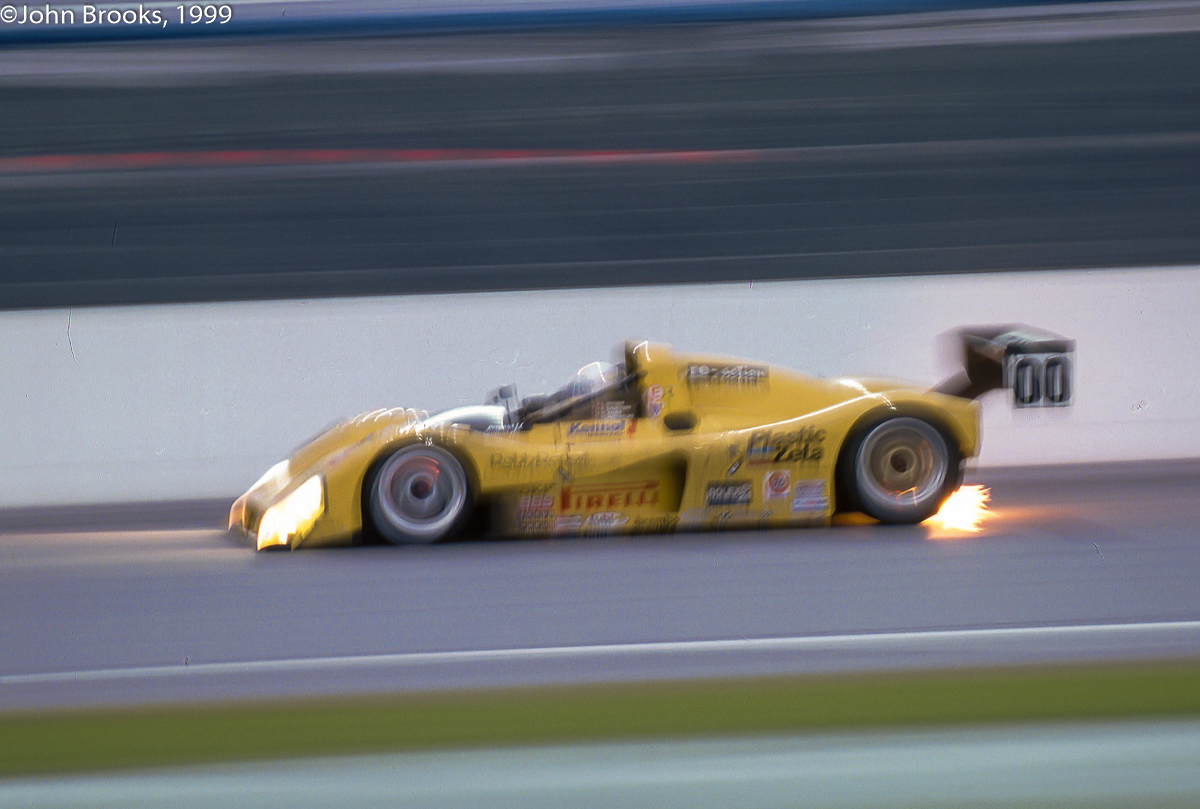

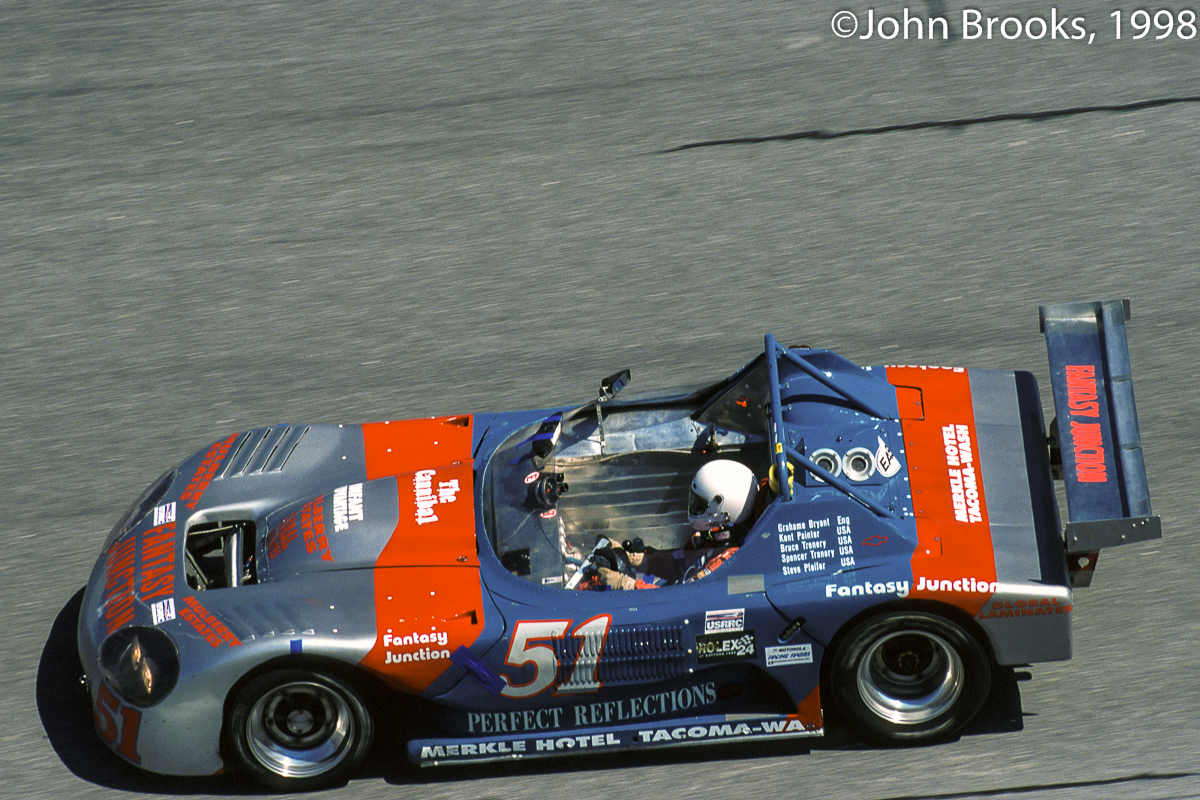

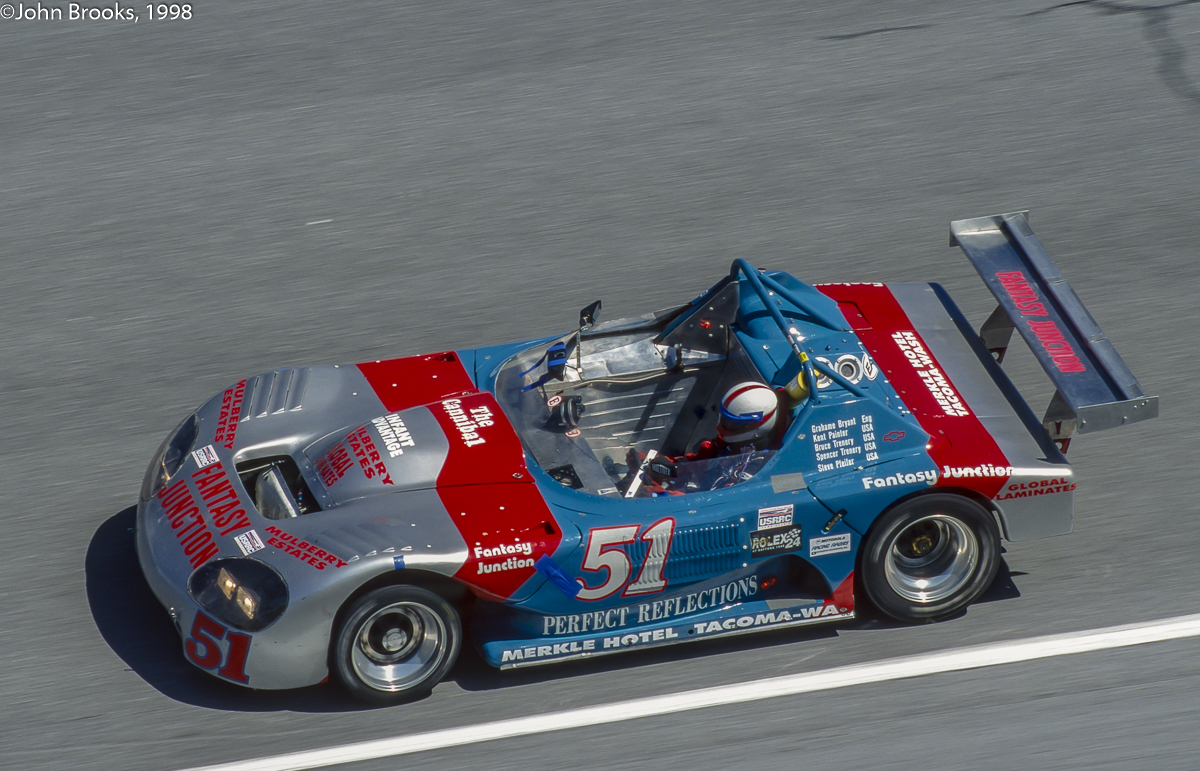

Back at the turn of the century some frankly weird contraptions would show up and ‘race’ at Daytona during the 24 Hours. This pioneering spirit was very much in the ‘run what you brung’ tradition and is somewhat missed in these politically and corporately correct times. In 1998 the Chevrolet Cannibal was oddball of the year, in fact there are grounds for thinking that it would be oddball of any year.

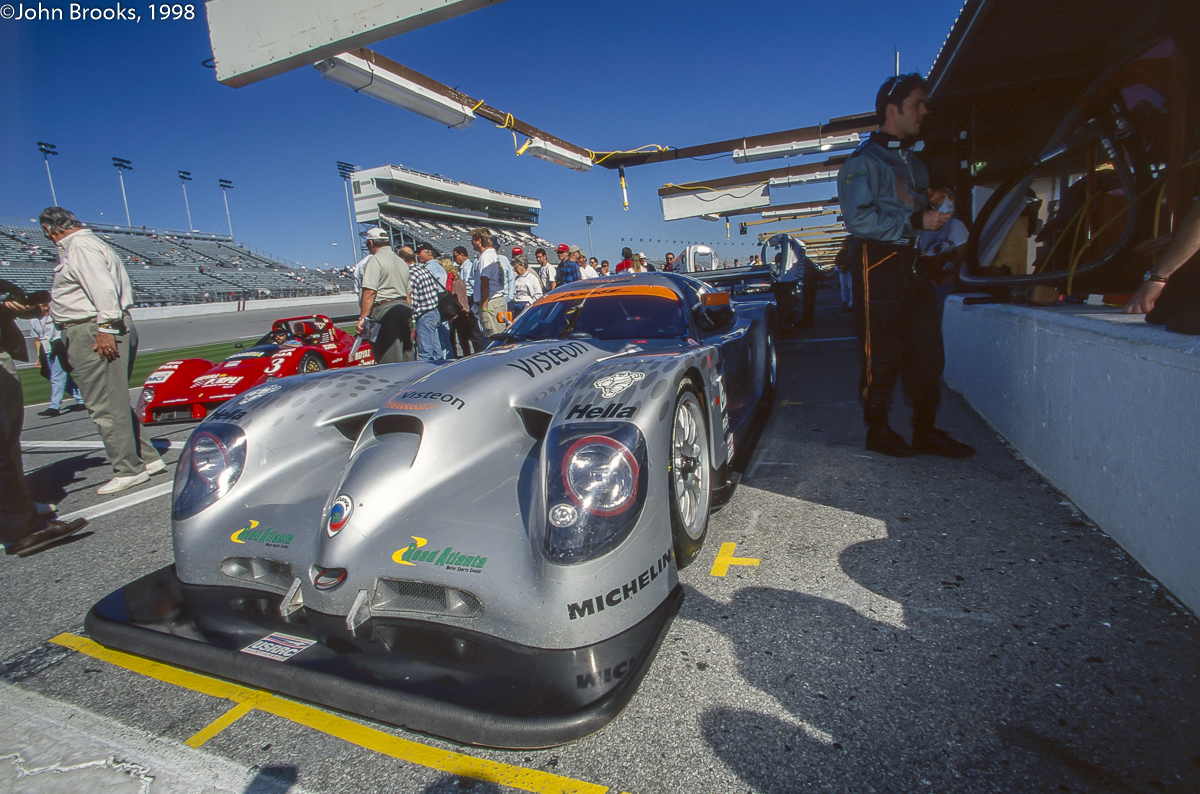

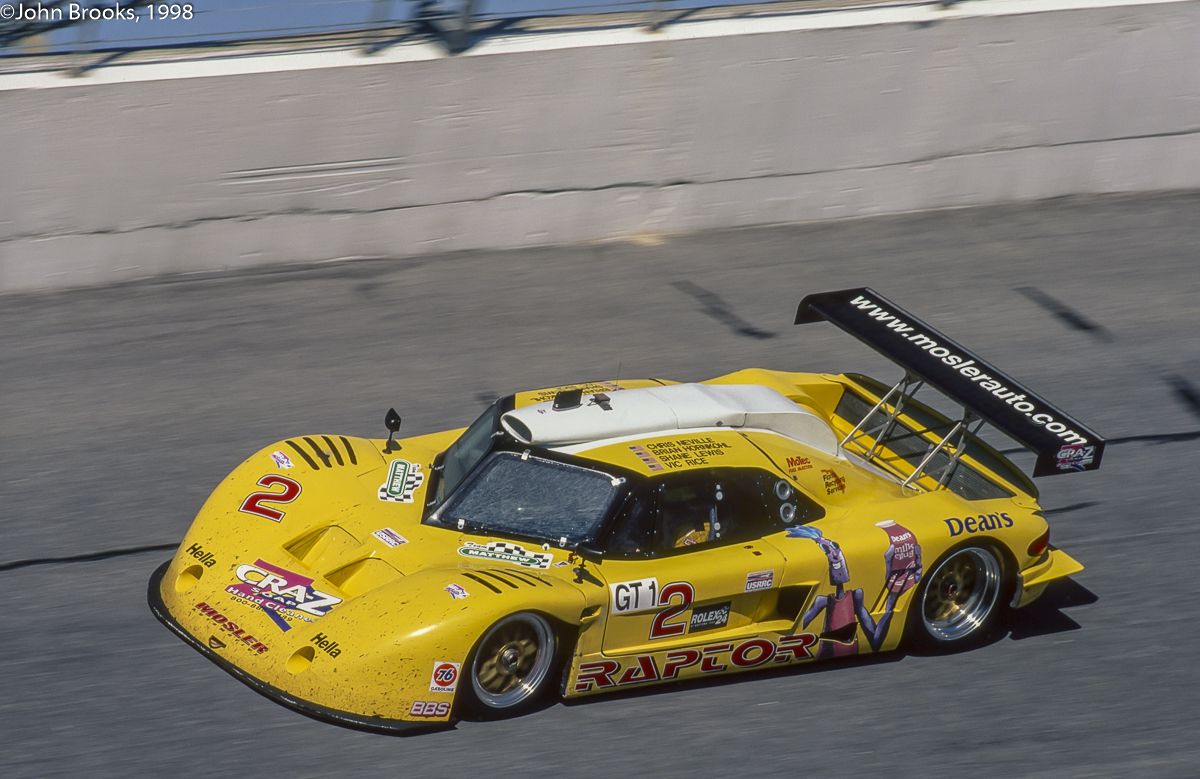

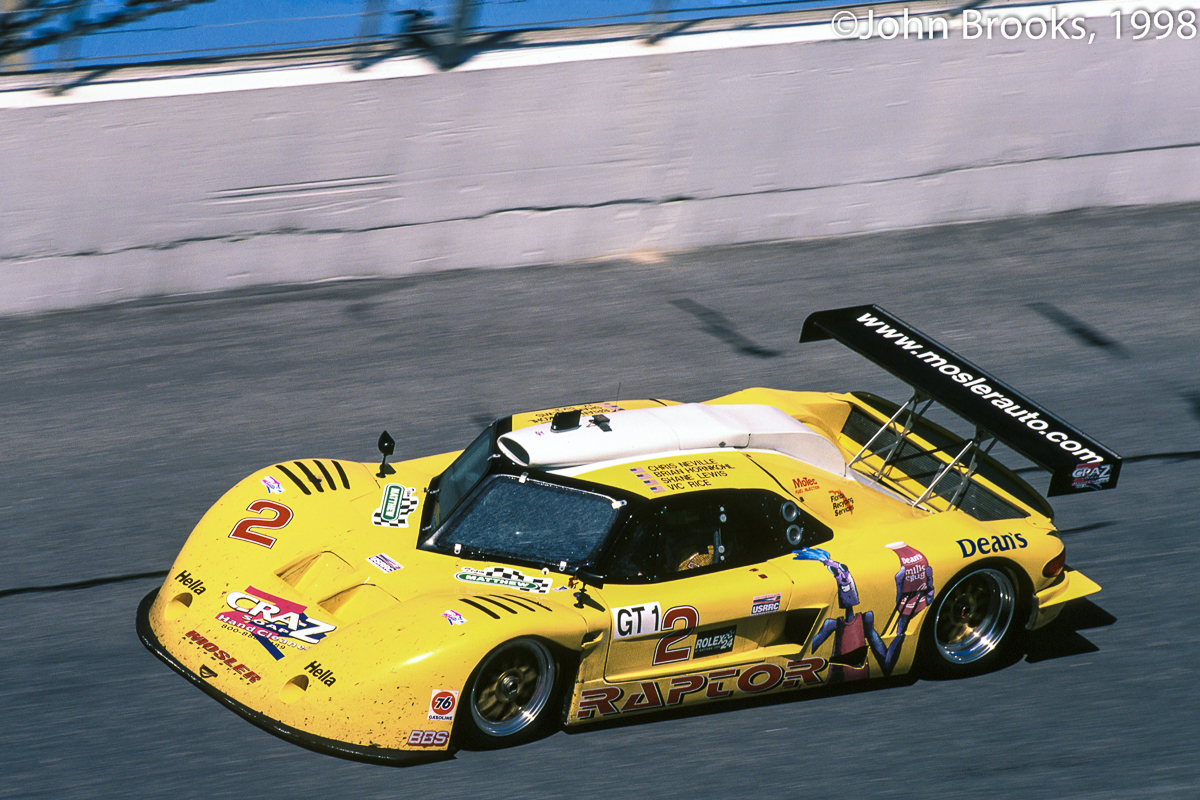

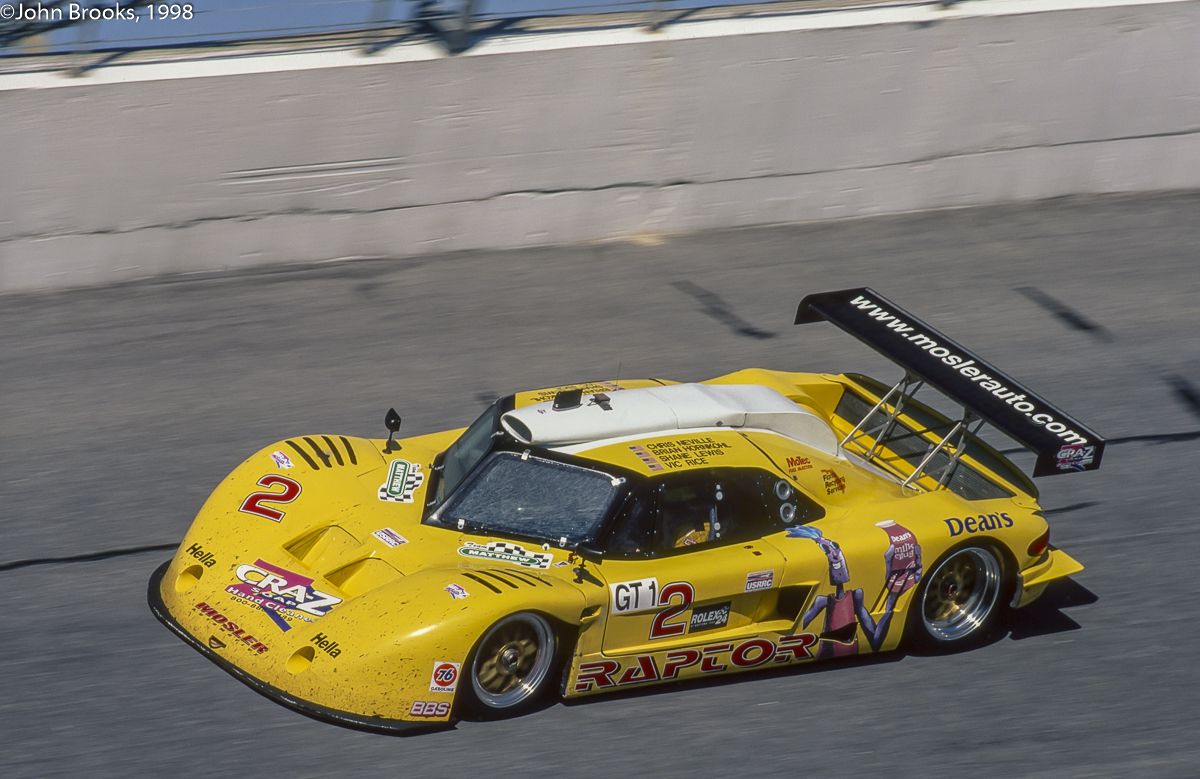

1998 also saw the Mosler Raptor take to the tracks, designed it would appear by Captain Nemo, with the distinctive split screen. At home at Turn Three or 20,000 leagues under the sea…………….

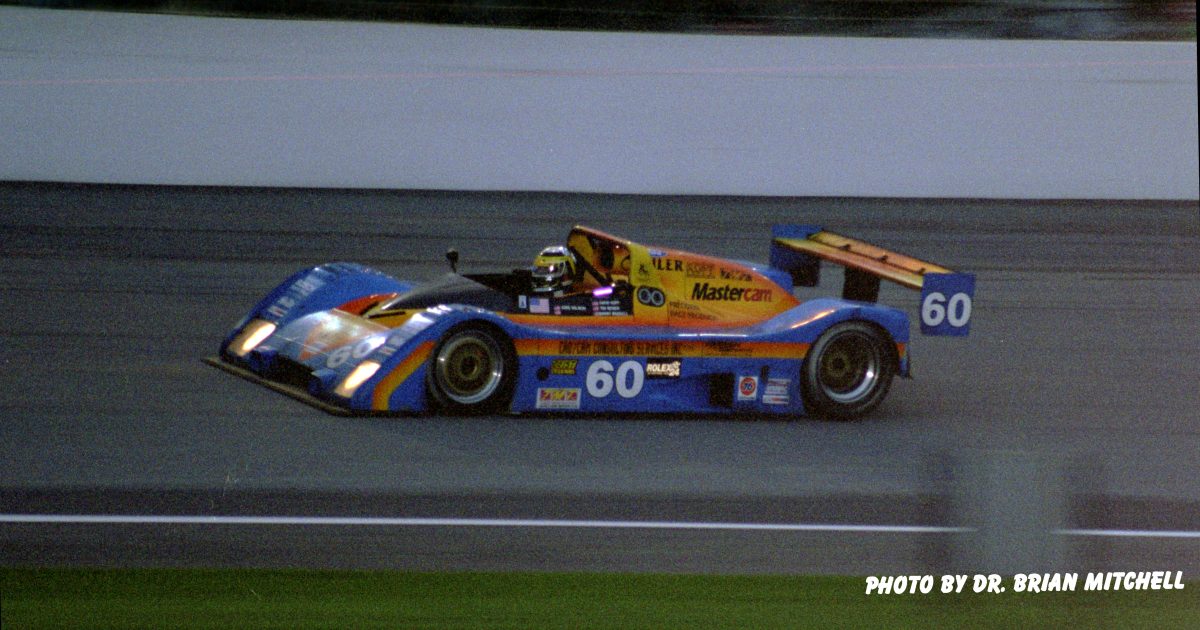

Other left field entries would include the Keiler KII which was a development of a Chevron B71. Powered by the ubiquitous Ford V8 it was a good example of the can-do engineering spirit that ran through the North American racing scene in the last decade of the century.

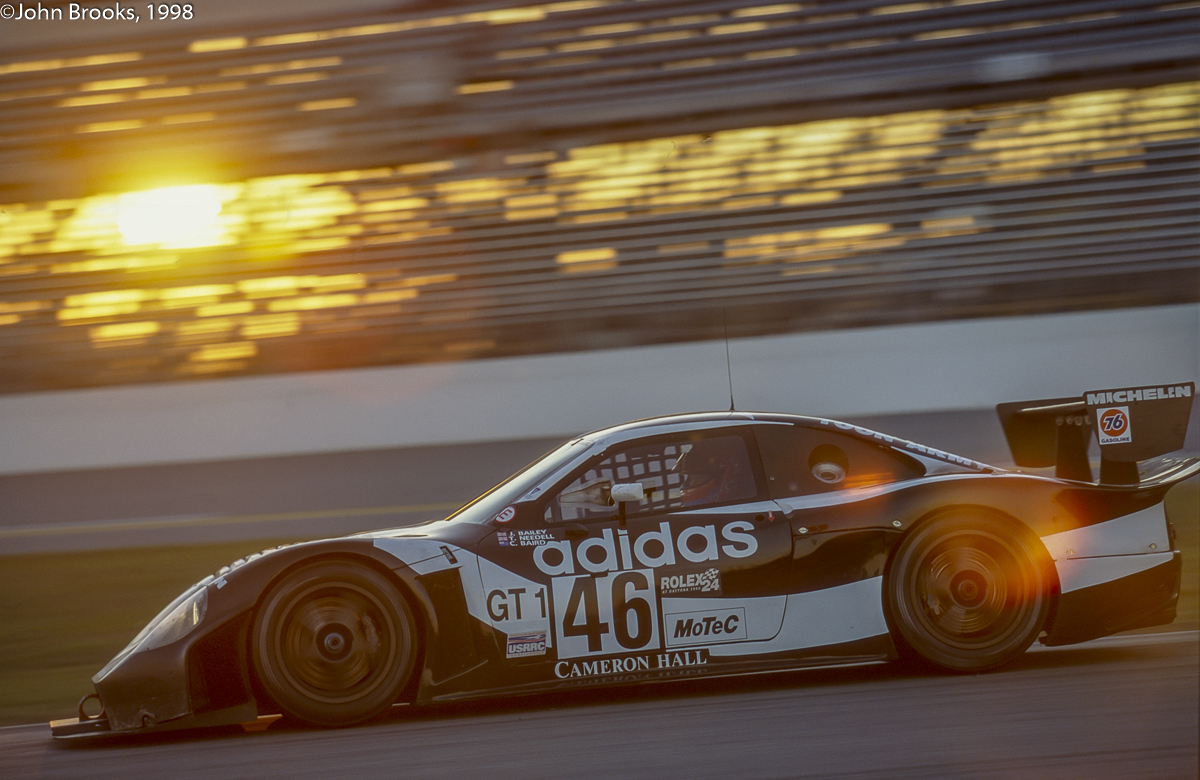

As mentioned earlier the GT1 class should have provided stiff opposition to the leading prototypes. However the powers that be decided that a CanAm car would triumph, so the regulations were changed, not for the first, or the last, time in Volusia County. The Panoz pair with an all-star line up of Eric Bernard, David Brabham and Jamie Davies in #99 and Andy Wallace, Scott Pruett, Doc Bundy with 1987 World Champion, Raul Boesel, in #5 should have been rattling the Ferraris and the Dyson squad in the speed stakes. However………….

The Porsche 911 GT1 trio should also have been there or there about, but USRRC, no doubt under instructions from above, had other ideas. Ballast was added and there were smaller restrictors if the GT1 had carbon brakes or electronic engine management – hello the computer age! – the final cut was reducing the fuel tank size from 100 to 80 litres to match the Can-Am cars. It was all a bit farcical and it fuelled the rivalry between Panoz and what was to become GrandAm. The ‘not invented here’ attitude was alive and flourishing.

There was the usual pre-race ballyhoo, speeches, songs, prayers and parades. Former heroes rumbled round the track at a dignified pace, provoking this cop to bellow incomprehensible instructions to move which were largely drowned out by the engine noises, this despite being in a place that was allowed by our passes……….my way or the highway…………..it was easier to leave than try and argue.

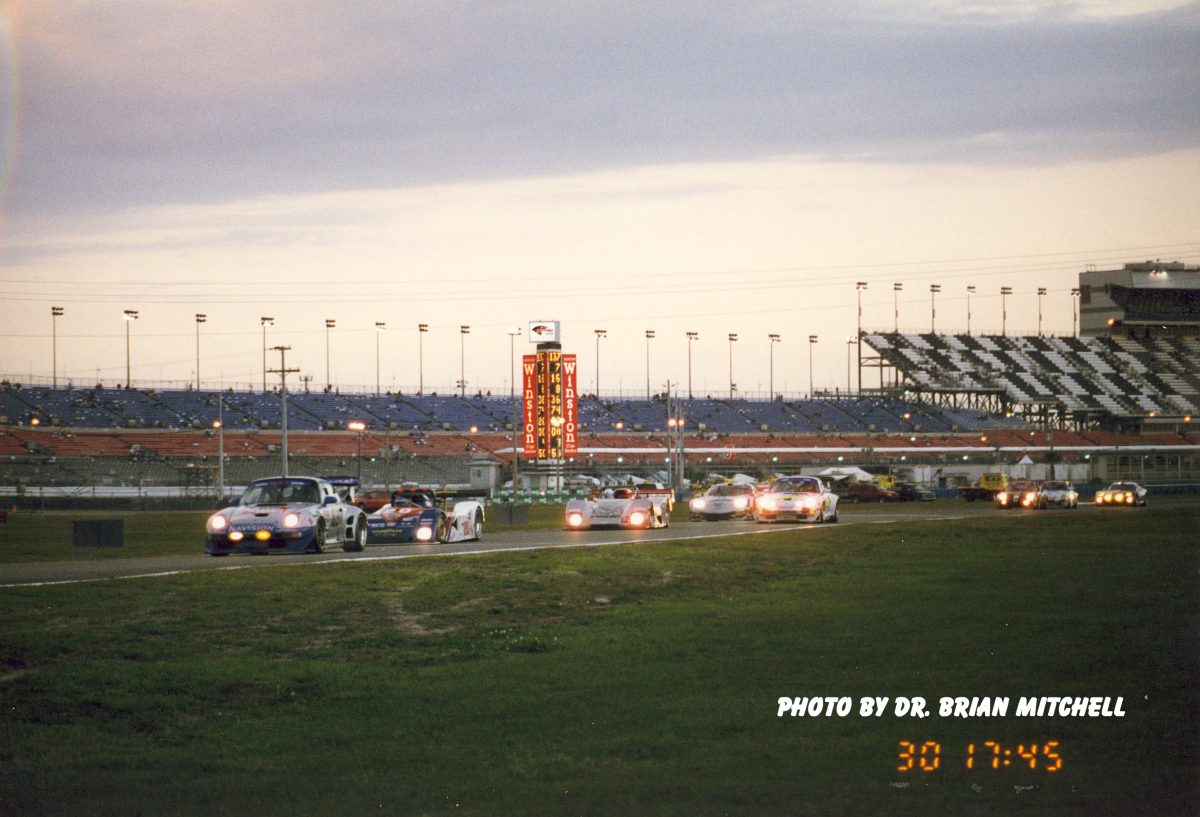

A full grid of 74 cars took the start under blue skies. As I have learned with 24-hour races, and the Rolex in particular, everyone heads off for the first corner with optimism in their hearts but it does not take long for the cracks to appear in even the best racers. One by one the favourites are hobbled to a greater or lesser degree, Daytona International Speedway has a deserved, and hard earned, reputation for being cruel to the aspirations of racers and their teams, the 1998 Rolex 24 would be no exception to this rule.

The race ran to plan for the leaders till the second hour. A full course caution was spotted by Andy Wallace in the Panoz as he headed into NASCAR four and he lifted off, just as James Weaver’s R & S was following him a full pelt, the resulting collision effectively ended both cars chances though both plugged away after extensive repairs, neither was running at the finish.

Doyle-Risi was next to stumble. First a pit official waved Eric van de Poele out of the pits even though the exit was closed, then the mistake was compounded by neglecting to inform Race Control, a two lap penalty was the consequence. Shortly after night fell the Belgian crashed out at the West Horseshoe, knocking out both himself and the Ferrari from the race.

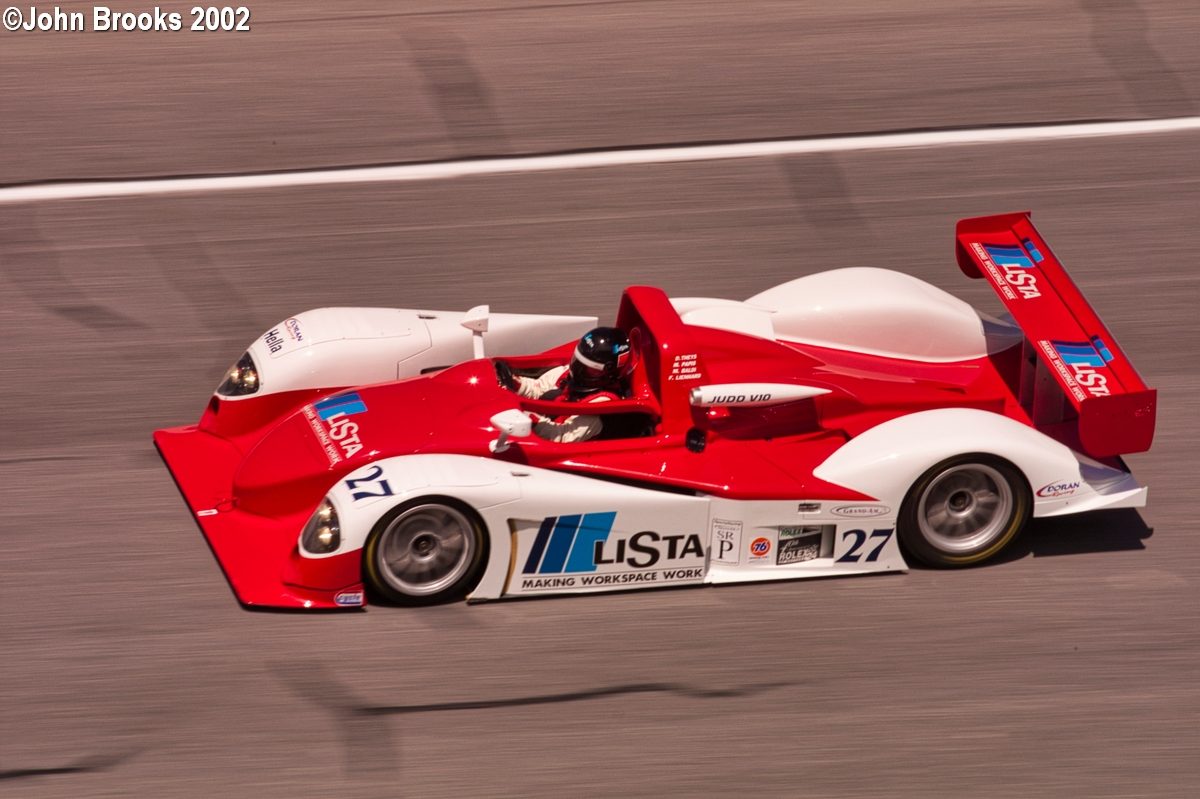

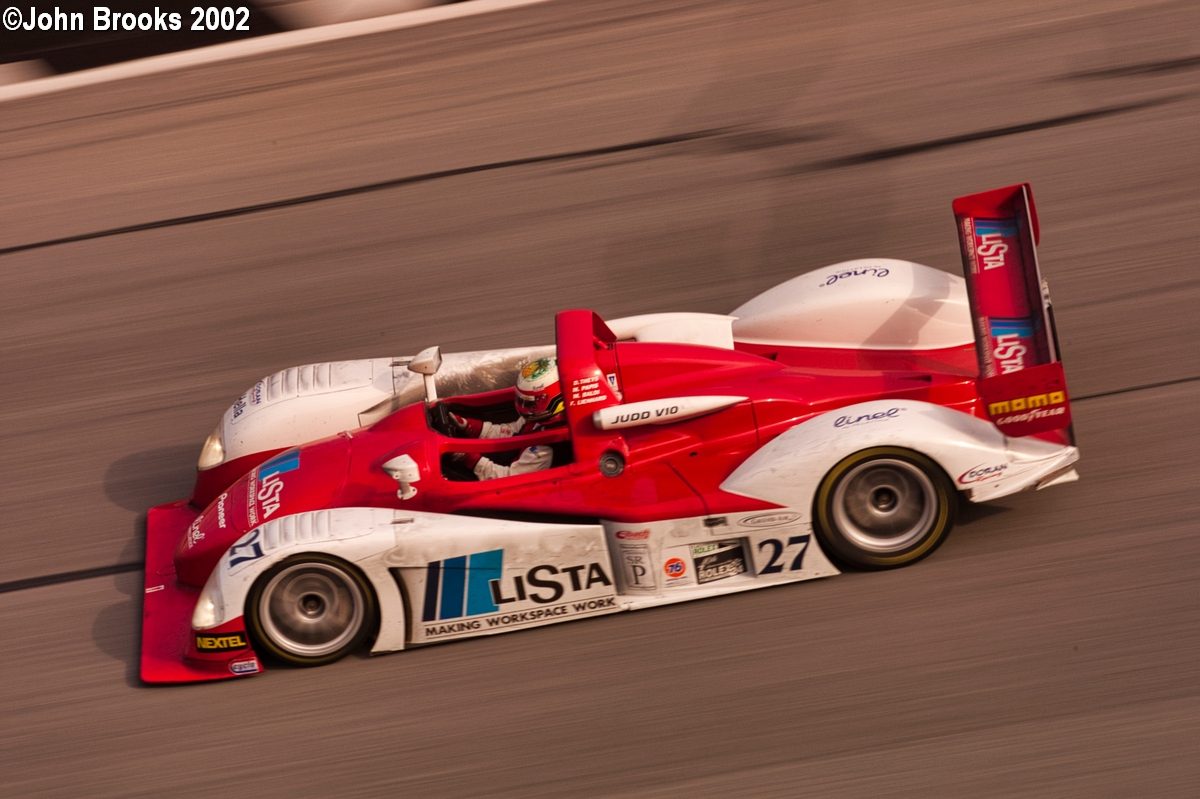

The lead was taken on by the Scandia Ferrari with the #20 Dyson car giving chase. Around 04.00 on Sunday advantage switched to the latter as the 333 SP suffered first a sticking throttle, then the transmission caught fire, another leading contender was out.

This left Dyson on target for a successive victory but the Racing Gods had other ideas. The engine started to give concern and with about three hours to go matters came to a head with the car being forced into the pits while smoking and leaking fluids………..another dream dashed.

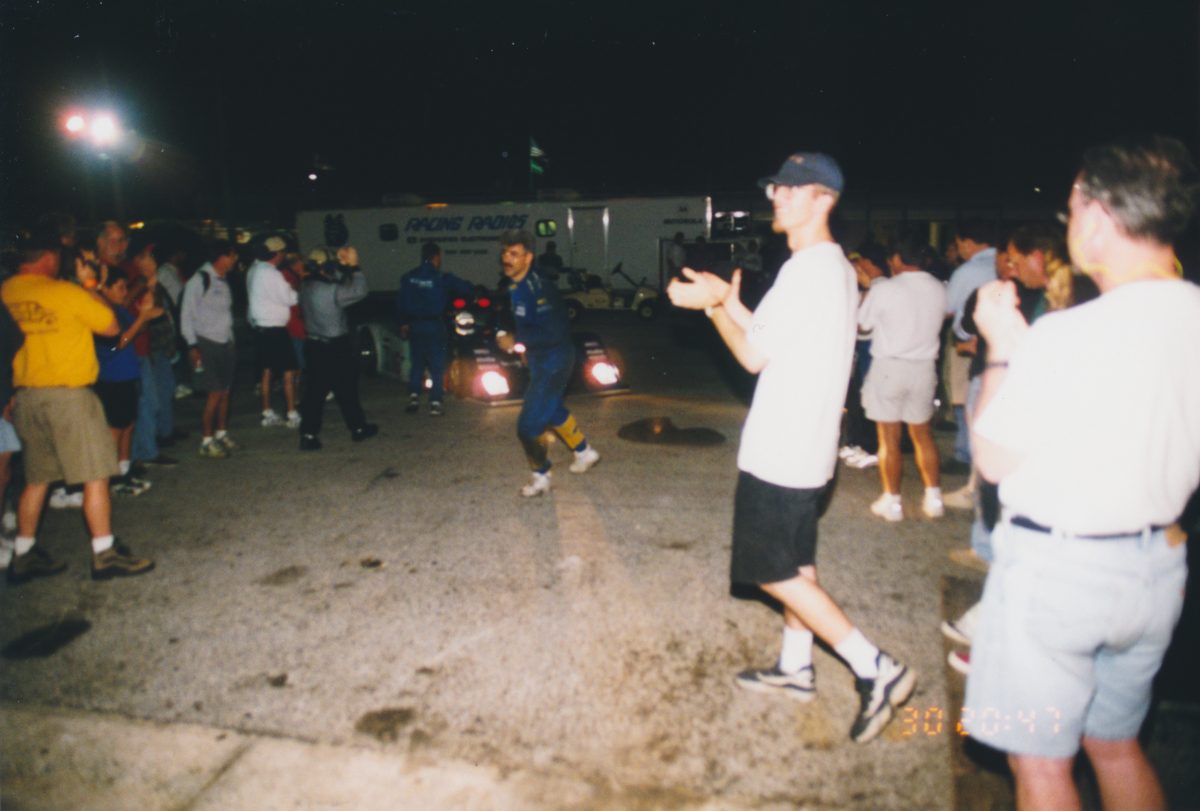

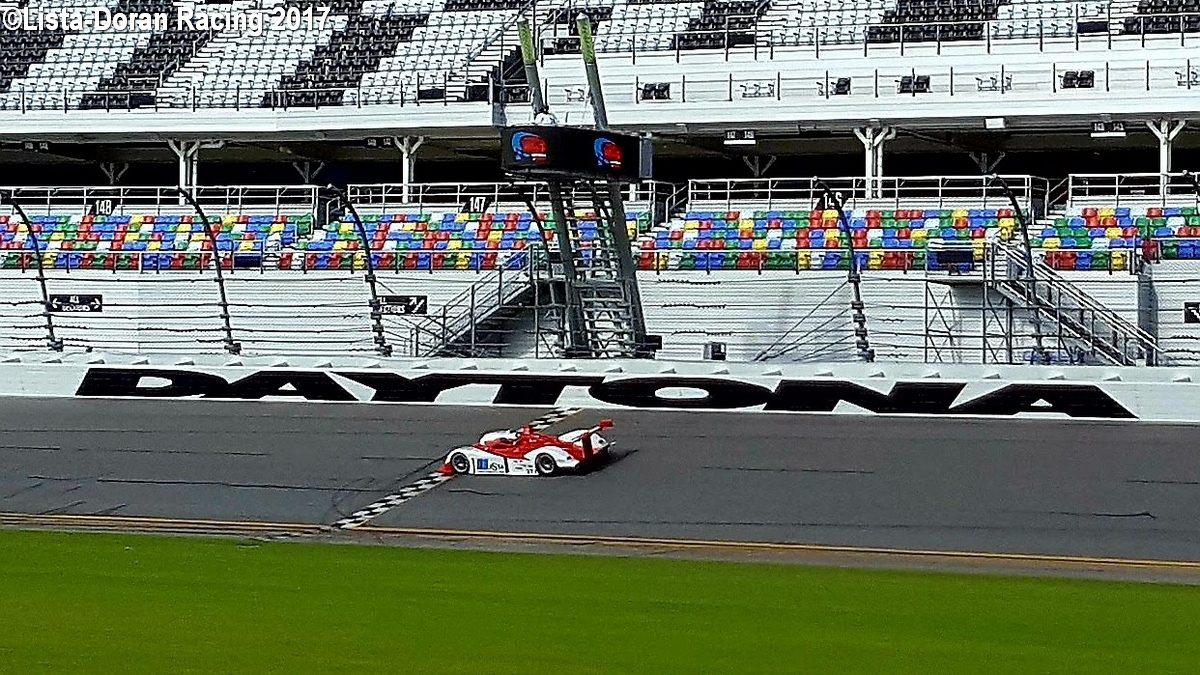

While Dyson were suffering despair the Moretti Ferrari was now in a lead that it would not surrender. Momo took the final stint, he had earned that right the hard way.

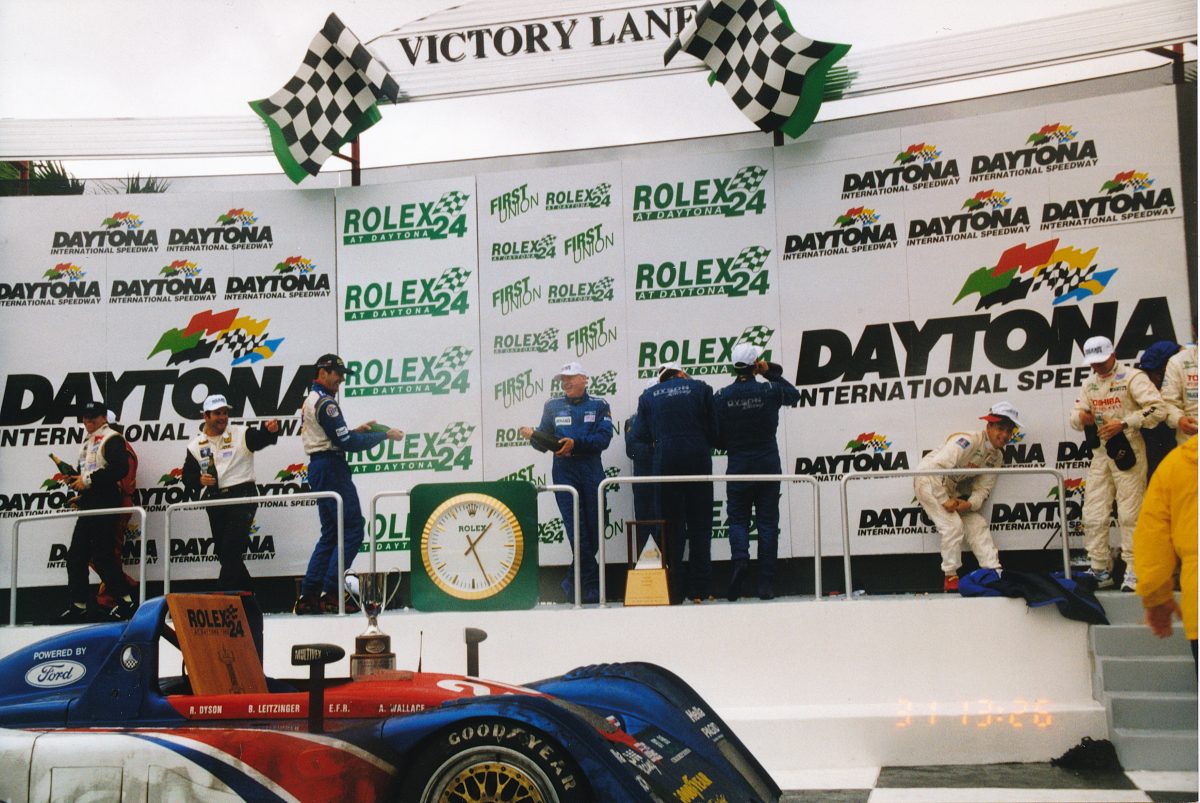

There were emotional scenes on the podium, a dream had come true, Momo had his Rolex. The Italian veteran would have an Annus Mirabilis in 1998 taking victory at both the 12 Hours of Sebring and the Watkins Glen Six Hours, throw in a finish at Le Mans and it was time to leave the stage.

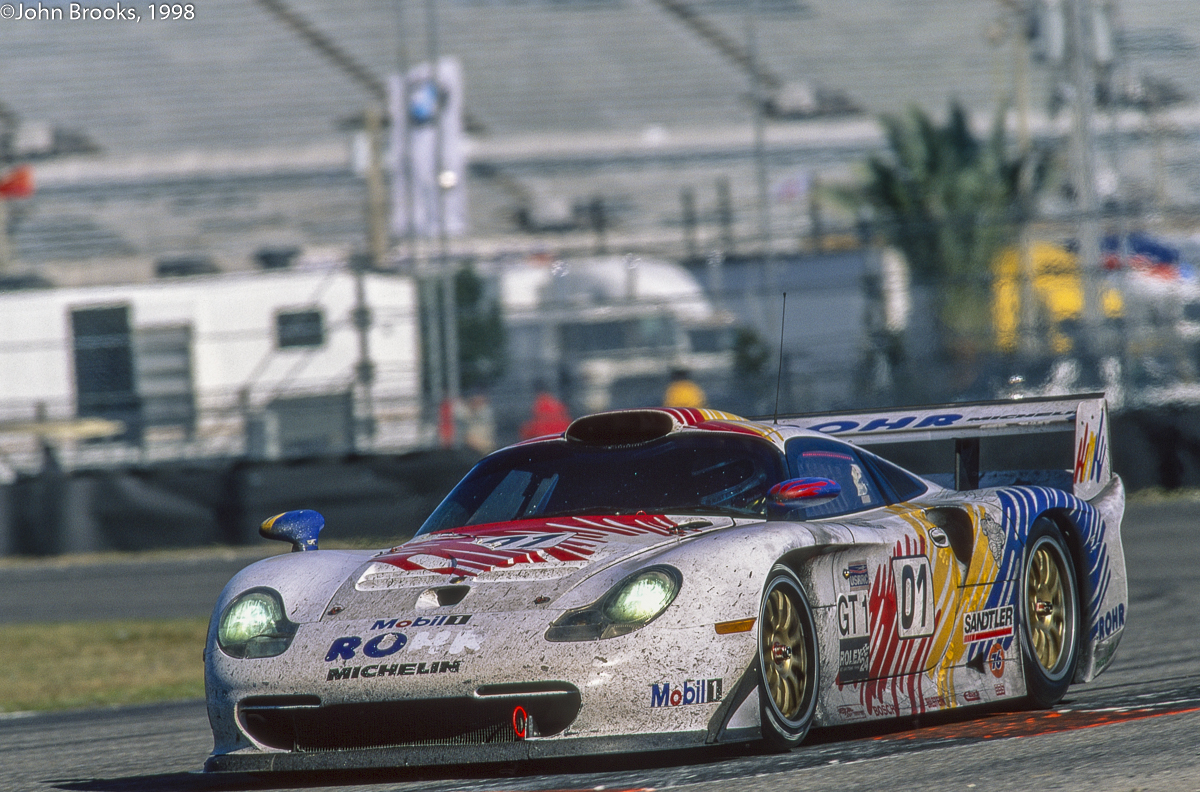

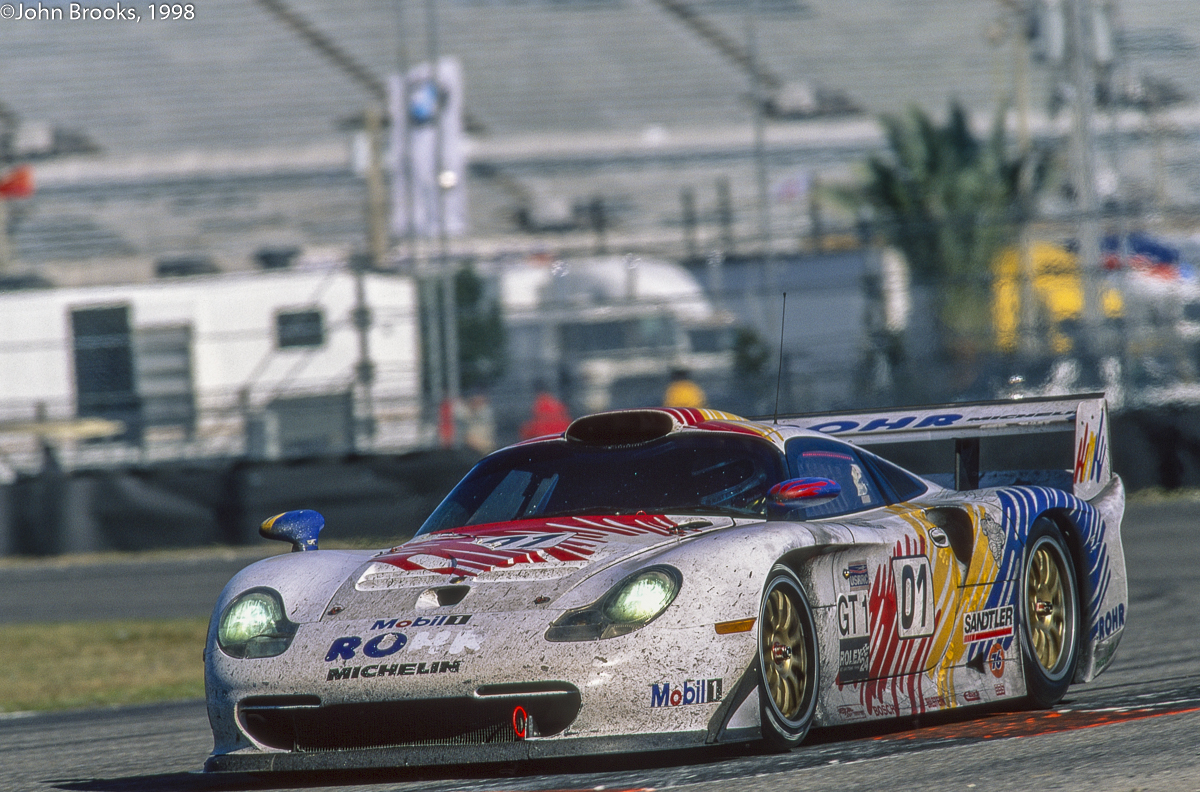

What of the other places? In spite of the best efforts of the USRRC to slow the GT1 entries they were there at the Chequered Flag, surviving the carnage that had engulfed the Can-Am runners. The Porsche 911 GT1 EVO of Rohr Motorsport finished second some eight laps down on the winner.

This was despite an all-star driver line up, almost an embarrassment of riches: Allan McNish, Jörg Müller, Danny Sullivan, Uwe Alzen and Dirk Müller enjoy the applause but no Rolex watches despite the podium and the class win, still rankles with a Wee Scot or so I am told. Not that any of us ever remind him, oh no sireee…………

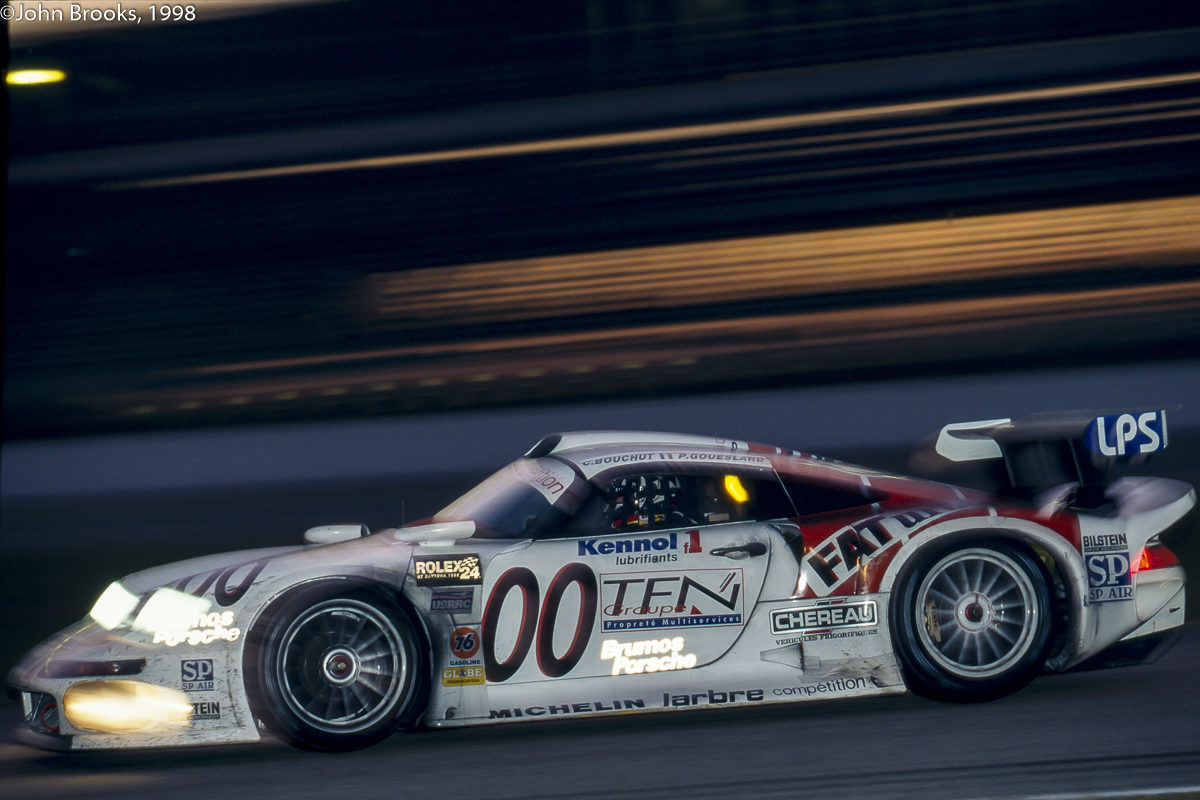

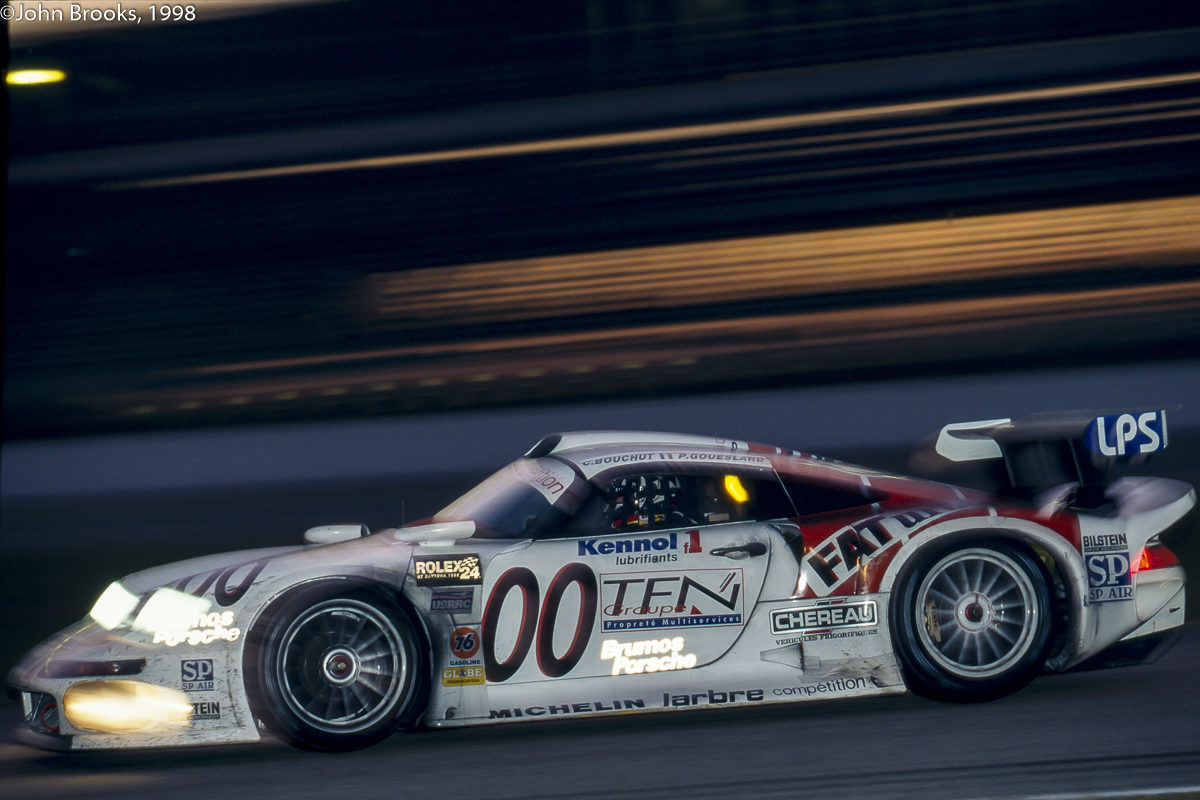

Third spot was occupied by another Porsche 911 GT1, the Larbre Compétiton entry of Christophe Bouchut, André Ahrlé, Patrice Goueslard and Carl Rosenblad………….a top class effort, much as we have come to expect from Jack Leconte’s outfit.

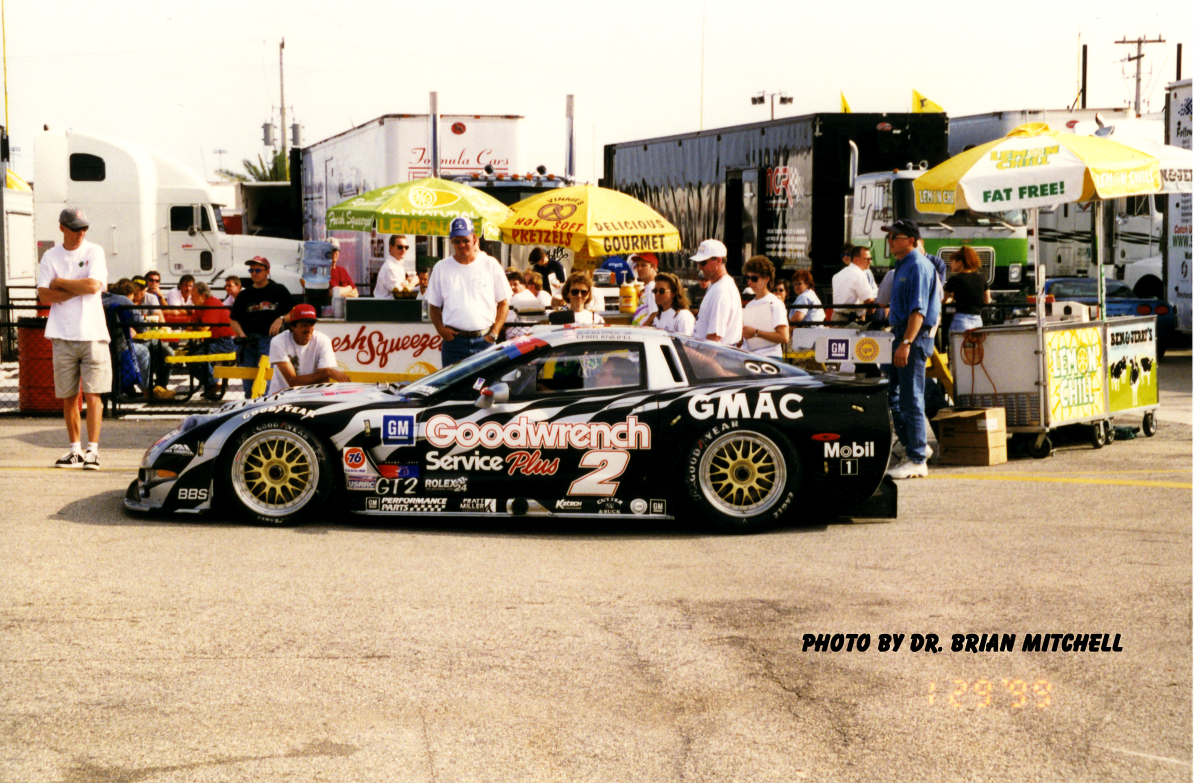

Porsche also took GT2 honours with the evergreen Franz Konrad guiding his squadron of gentlemen drivers to victory in the 911 GT2. Toni Seiler, Wido Rössler, Peter Kitchak and Angelo Zadra all did their bit in this fine result.

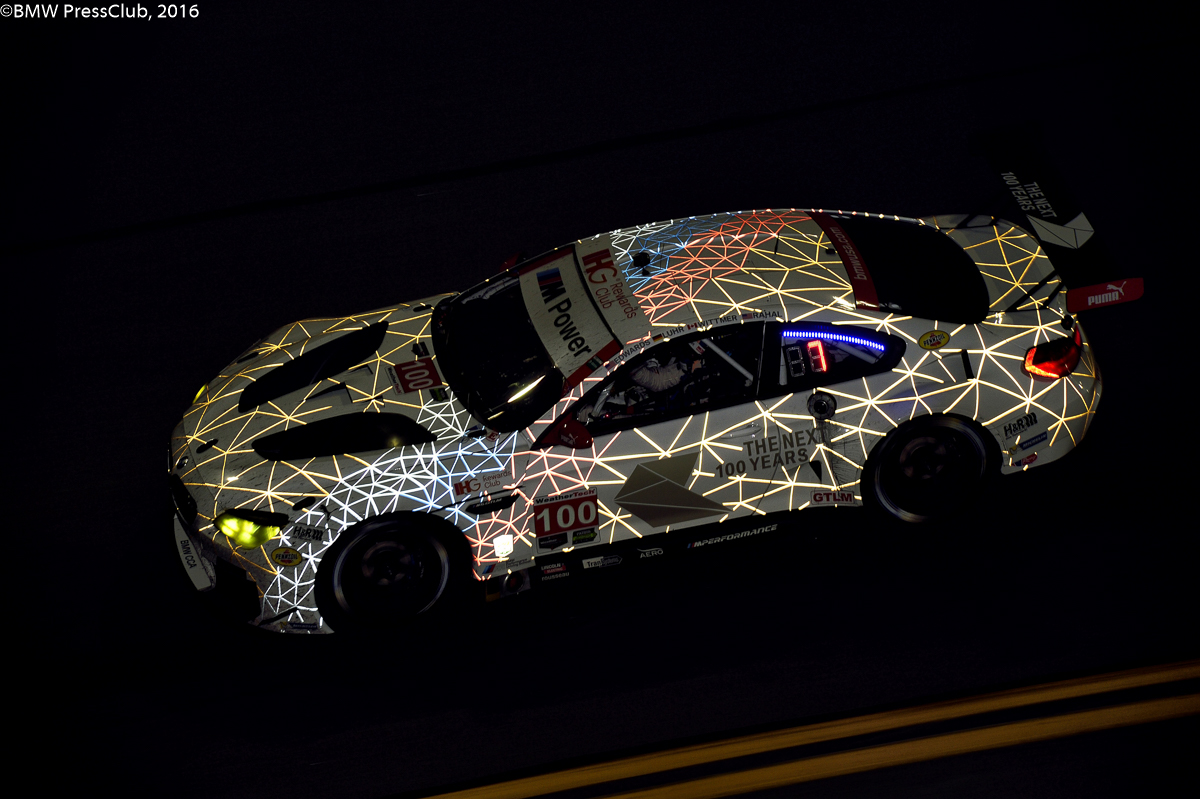

The final class winners were PTG and their BMW M3. Bill Auberlen, Boris Said, Peter Cunningham and Marc Duez climbed the top step of their podium at ‘The World Center of Racing’ to receive their trophies, no false modesty at DIS.

The eternally youthful Bill will line up for the factory BMW outfit this weekend, as will his fellow class winner from 1998, Dirk Müller. Dirk will be hoping that his Ford overcomes Munich’s finest.

What did I learn from the experience of my first Rolex? Well like most Europeans who go racing to North America I had the idea that we were more professional in Europe, with our F1, our Le Mans, our traditions. I soon realised that was complete bollocks, the driving, engineering and every other aspect of motor sport on that side of the Atlantic was the equal of anything over here. Just look at the record of Penske, Pratt & Miller, Chip Ganassi and see the facts as they are.

If some of the officialdom was dodgy or the decisions were difficult to understand then consider some of the horror stories perpetrated over here. If security was inclined to make things up on the hoof, then recall dealing with Belgian police, the CRS or any of the private security firms now involved……….I rest my case. It certainly opened my eyes and made my decision to follow the ALMS in the early years a certainty.

Did I learn anything else? Well don’t go drinking with Julian Bailey in an airport bar, we almost missed the flight home as we got well refreshed. We picked up the last call and boarded the plane to jeers of those who knew us, I think I slept well that flight. It was the first chapter in a grand adventure…………..maybe I am due a new one soon.

John Brooks, January 2018