Our Special Correspondent was at the 90th Anniversary Le Mans 24 Hours. He shares with us a different but important historical perspective on the world’s greatest motor race.

The week leading up to the Le Mans 24 Hour race is always rewarding for a motor car enthusiast. This year marked 90 years since the first running of the race in 1923 and on the Tuesday there was a special celebration of the old Pontlieue Hairpin – the original circuit ran deep into the southern suburbs of the city, doubling back at a tight hairpin in Pontlieue, a favourite spot for those early photographers as the cars were travelling comparatively slowly.

The roads still exist although the more distant approach sections are unrecognisable today as they have to cross the ring road. The corner was suitably adorned with signs of the time:

The President of the A.C.O. Pierre Fillon unveiled the traditional sign marking the corner, having arrived in a contemporary (and boiling!) Vinot-Deguingand, a French marque which took part in the very first race.

The 1924 –winning Bentley also did some runs. The corner was foreshortened for 1929-31 by which time the A.C.O. had purchased the land between the start/finish area and Tertre Rouge. Here they opened in 1932 the section of track which still comprises the Esses, and Pontlieue fell into disuse from then onwards.

Present at the ceremony was the 1923-winning 3-litre Chenard et Walcker.

Chenard et Walcker (not to be confused with another French marque, Chenard, the cars of Louis Chenard one of which ran at Le Mans in 1924) was in the mid-Twenties France’s fourth largest car manufacturer, turning out some 100 cars a day in its factory at Gennevilliers in Paris. Not only did it take the first two places with its o.h.c. 3-litres in the first race in 1923, but a smaller-engined version won the 2-litre class in 1924.

The company is also remembered for the exciting little Henri Toutée-designed 1100 c.c. “tanks” which had widespread success in sports car races in 1925/26. Two such cars, one with a larger engine, ran as private entries at Le Mans as late as 1937, albeit with no success.

The museum at the circuit can always be relied upon to vary the exhibits and some recently loaned cars are worthy of mention. This year sees a serious revival of the Alpine marque with Renault not only developing a new production Alpine sports car (in collaboration with Caterham) but also adapting an Oreca 03 LMP2 car to run in the 24 Hour race as an Alpine A450. It was, of course, 50 years ago that Jean Rédélé’s company made its first venture into endurance sports car racing with the M63 coupés; there is one currently on show in the museum.

Their first attempt at Le Mans was unfortunately shadowed in tragedy – one of the Project 214 Aston Martins dropped all its oil on the Mulsanne Straight on the Saturday evening causing a number of cars to crash seriously, one of which was the M63 of the young Brazilian Alpine agent, Christian “Bino” Heins. His car flew off the circuit, struck a telegraph pole and exploded in flames, giving the poor driver no chance of survival. Despite this setback, the Alpine cars went on from 1964 to score manifold victories in endurance races in the smaller categories, especially with their A210 coupés.

With a 3-litre limit slapped on prototypes from 1968, Alpine saw the opportunity to go for outright wins and Gordini developed a V-8 engine for them. This was initially tried out in an A210 coupé, this one-off prototype being re-named the A211.

The car was raced briefly and came to Le Mans for the Test Day, but it was clear that the engine was too powerful for the chassis and the all-new A220 was designed.

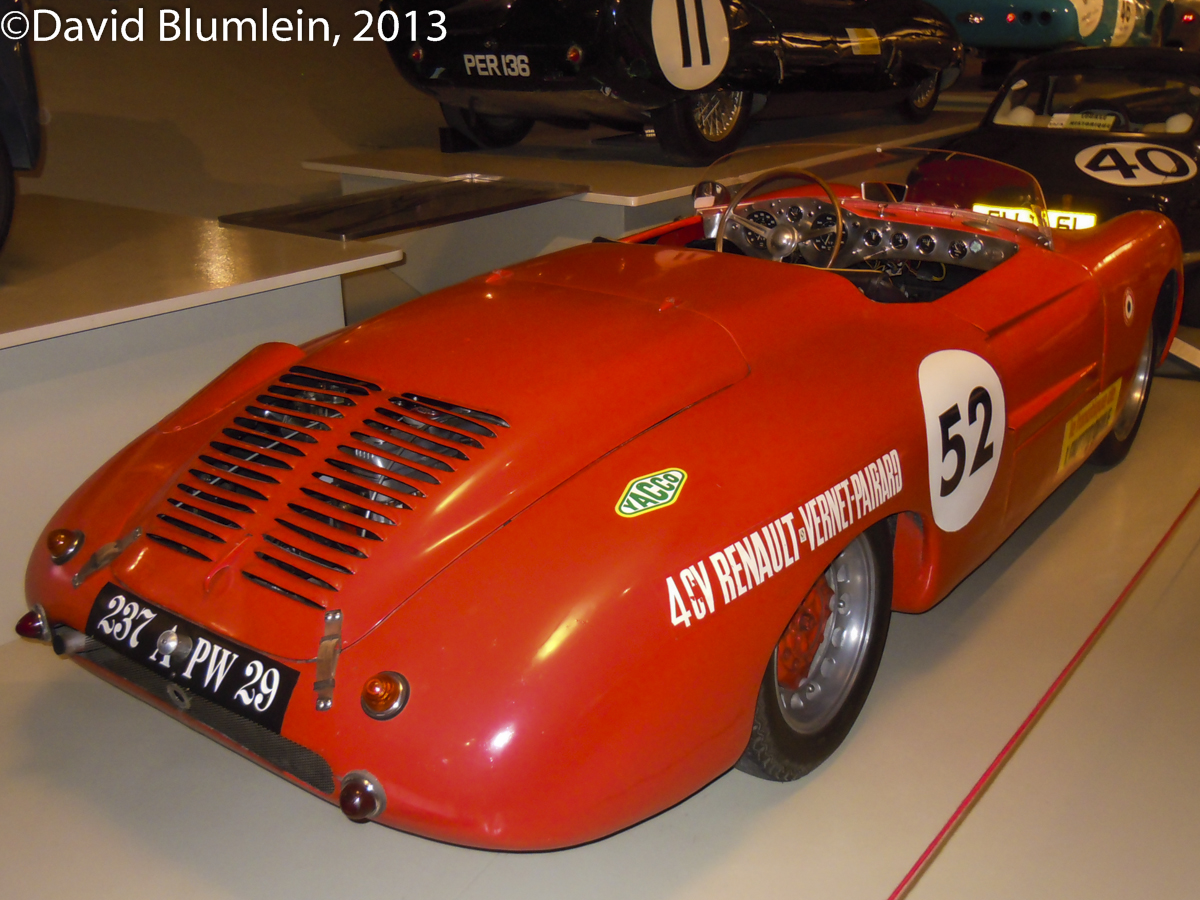

This is a V.P., a Verney-Pairard, the work of two enthusiasts, Just Emile Verney who had driven in every Le Mans race from 1931, and Jean Pairard, a Parisian industrialist. They were keen to create a not-too-expensive sporting car with a view to gaining the support of the Regie Renault for small series production. One of Pairard’s engineers, Roger Mauger, drew up a tubular chassis with all-round coil spring independent suspension and a Renault 4cv engine at the rear, the whole bodied by the French coachbuilder Antem. They took their first car to Montlhéry for some trial runs and the performance caught the eye of Franςois Landon, head of the Regie’s Competition Department. He recommended that they try for records and the car, duly adjusted aerodynamically with full wheel spats, ran in October 1952 at Montlhéry, taking eight International Class H records. The Paris Salon was just opening and Renault took over the car, giving it pride of place on their stand and re-naming it a Renault R1064!

This car ran with the necessary lights etc. at Le Mans in 1953 along with a new coupé V.P. which had an oversize cockpit roof to accommodate the corpulent Pairard! The “Renault R1064” retired in the seventh hour while the little coupé, much handicapped by its excessive frontal area, finished last. No long-term support for V.P. was forthcoming from Renault and the R1064 reverted to being a V.P. once more! It then received revised bodywork for 1954 when it returned to the 24 Hour race.

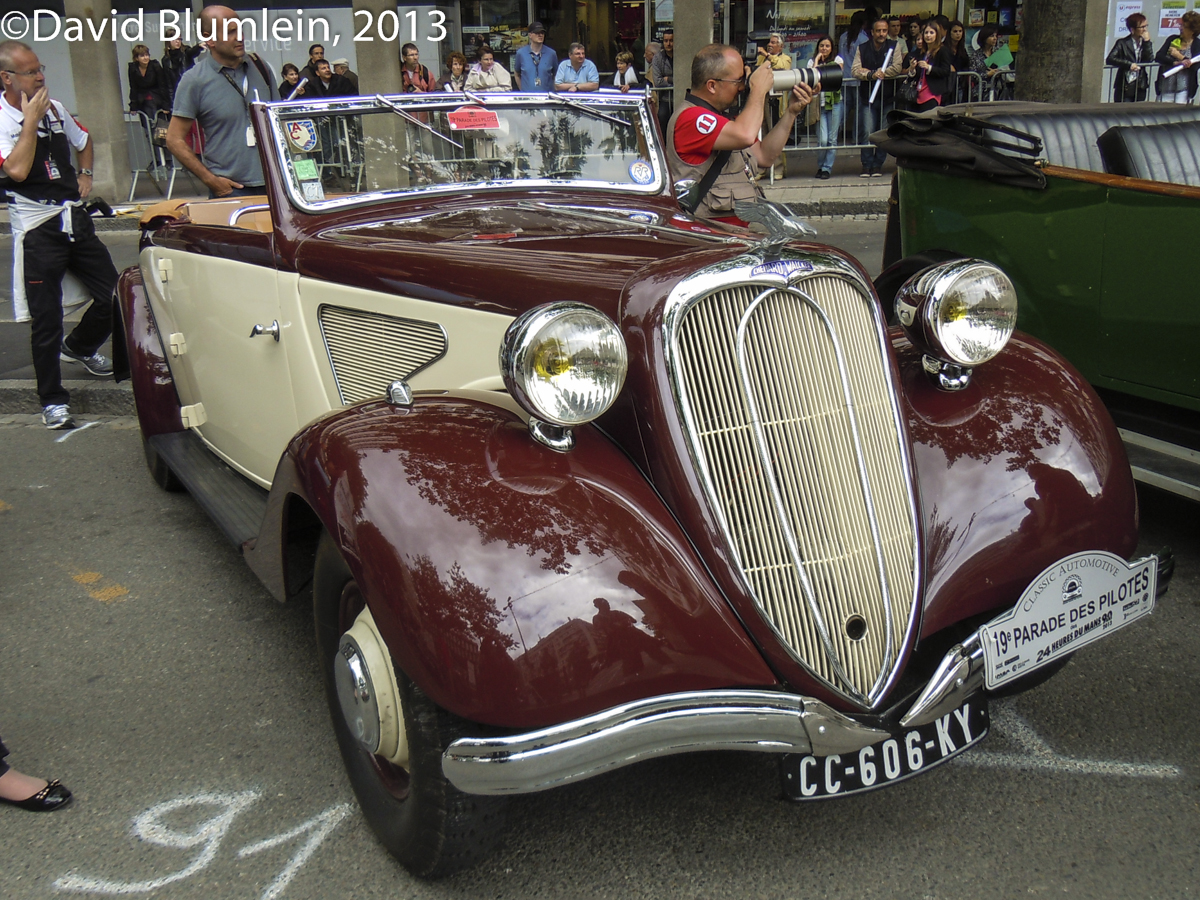

At the Drivers’ Parade, mercifully dry until the very end, it’s back to Chenard et Walckers. The real gem was this Torpille seen above.

At the 1927 Paris Salon Chenard et Walcker introduced two 1500 c.c. sports cars: one was a production version of their little “tank”, the Y8, and the other a more conventional model with cycle wings, this Torpille, the Y7. The latter was sold in “bleu France” as seen here, and both models were used in national competitions by private owners – no more works cars from the Gennevilliers company.

In the Thirties they made some technically interesting models such as this Super Aigle 24. Their Super Aigle range adopted front-wheel drive at the 1934 Paris Salon when Citroën more famously did the same, and they also used torsion bar independent suspension. This Super Aigle 24 dates from 1936 and has a Cotal electromagnetic gearbox. Alas, these advanced features did little to save the company which was taken over by Chausson who substituted Ford and Citroën engines. By the early post-war period the Chenard et Walcker name was on a forward-control 2-cylinder van soon to be Peugeot-powered and then Peugeot produced.

Perhaps it was appropriate that this year’s Alpine drivers should have been chauffeured in a Renault – a 1904 3.7-litre 4-cylinder Type U model.

There are always representatives of the pioneering De Dion Bouton company in the parade. Here we see an example of their popular ID model, dating from 1919. It is interesting to note that the company gave up using their famous De Dion rear axle as early as 1911/12 yet it is still used on today’s little Smart!

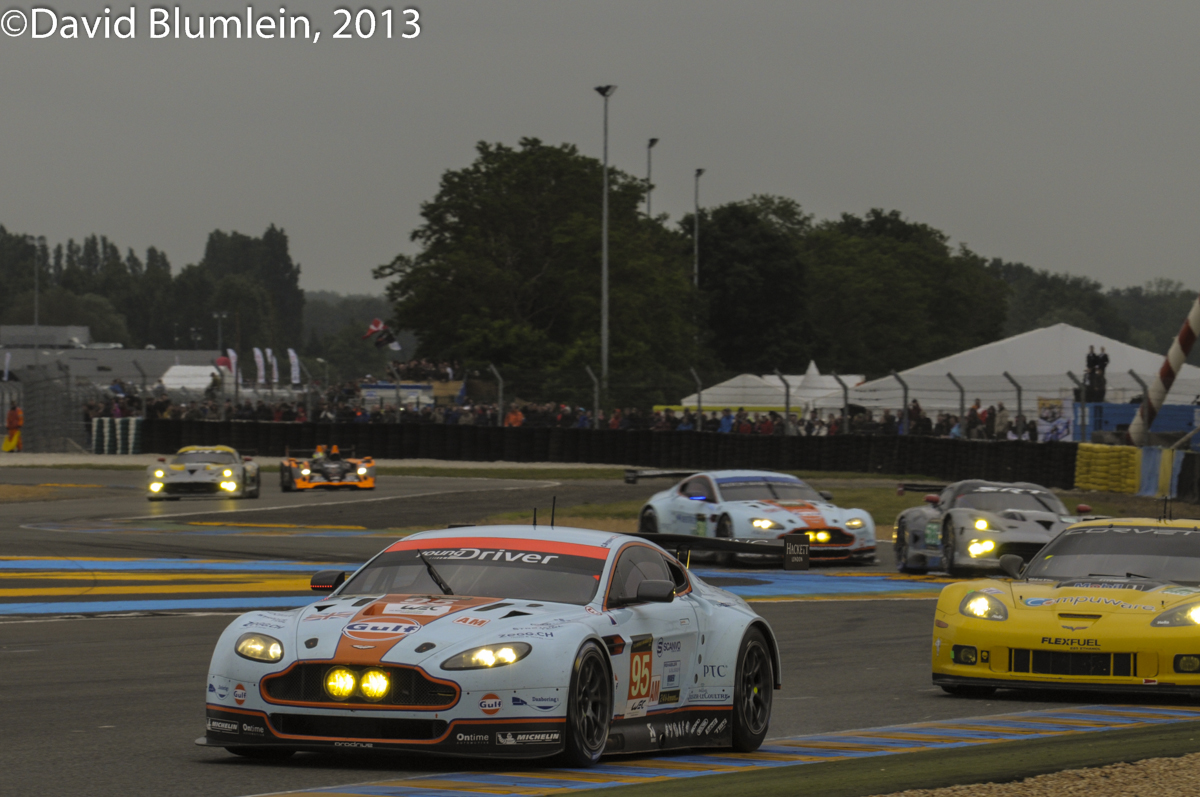

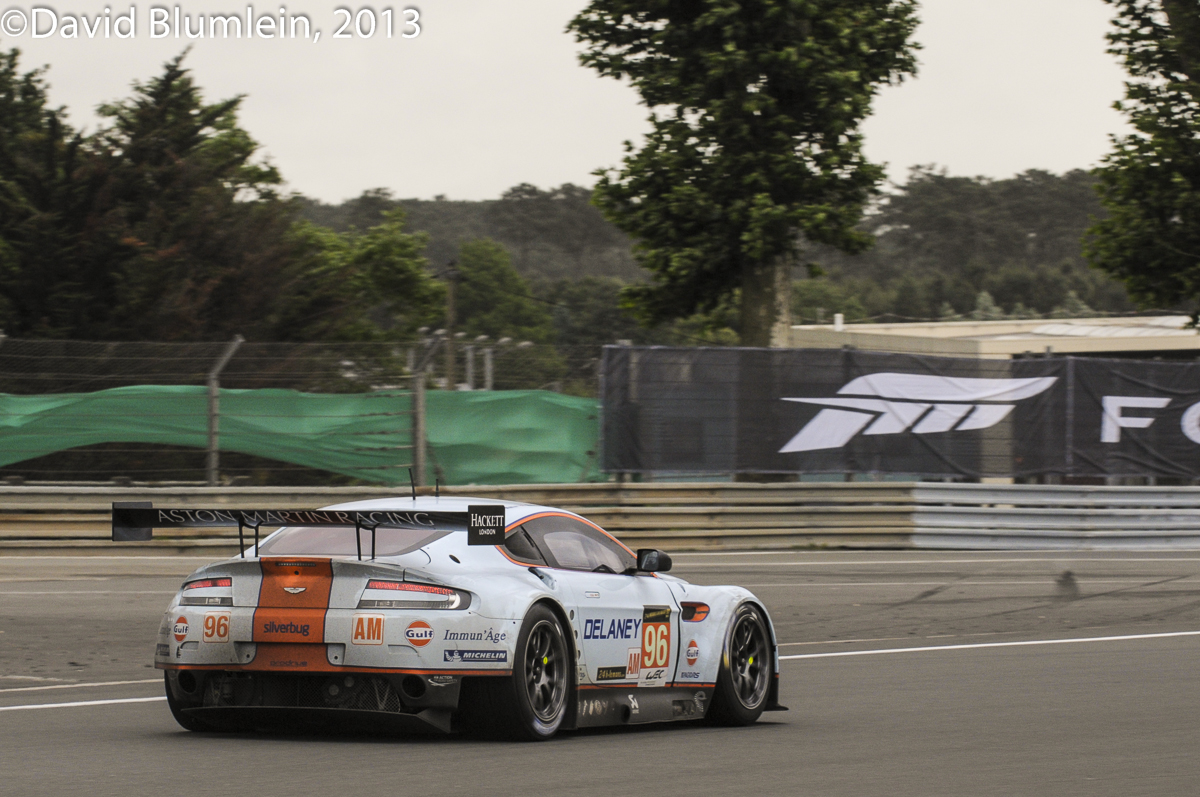

And so to the race. First, a small tribute to Allan Simonsen, by all accounts a lovely person and a highly-rated driver who tragically lost his life on just his third lap of the race. Here he is completing his second lap and starting his third fateful one just moments before disaster struck.

And here is his class team-mate passing the tragic spot at Tertre Rouge where the public road joins the private section of track. At the specific request of Simonsen’s family the Aston Martin team carried on racing.

Looking back at that first race ninety years ago, it is interesting to reflect on one or two similarities with today. In 1923 the organisers used army searchlights to illuminate the corners – here is the Dunlop Chicane illuminated using more modern technology:

And the public road leading to the Arnage corner is still basically as it was –

the left-hander at Indianapolis then the short straight to the right-hand bend.

And here is the road out of Arnage looking up towards what are now the Porsche Curves but used to lead to the Whitehouse Corner – that road is still there.

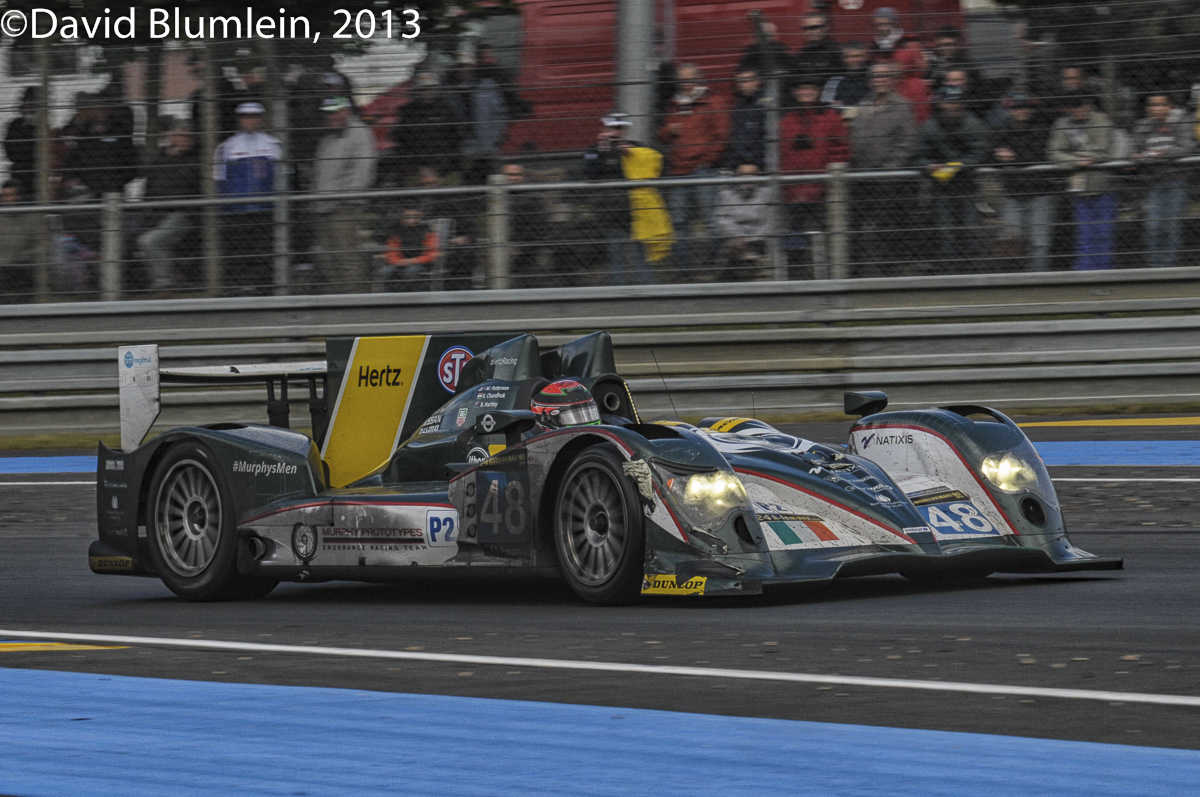

The gruelling nature of this race is reflected in the general state of some of the cars by Sunday. Here is the Murphy Team’s Oreca 03 looking distinctly grubby.

And two AF Corse Ferraris which have seen some battle, this was #71

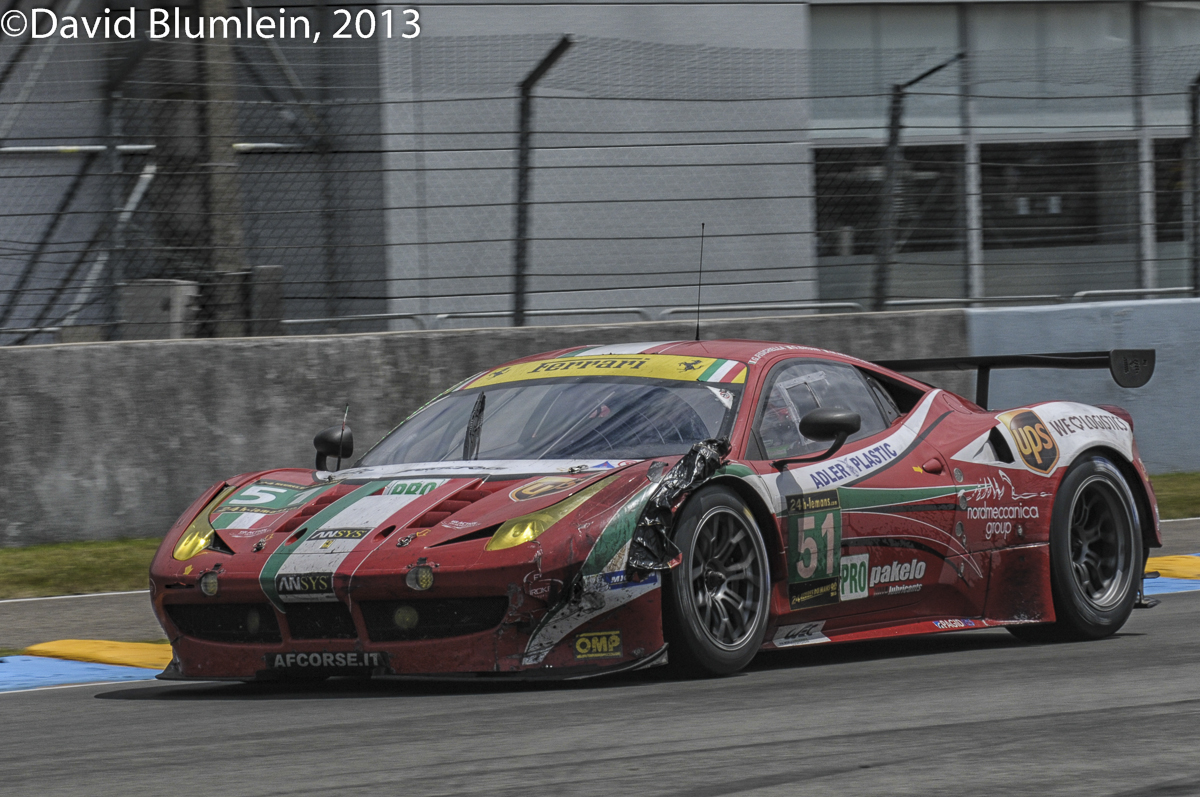

And #51 was not much better

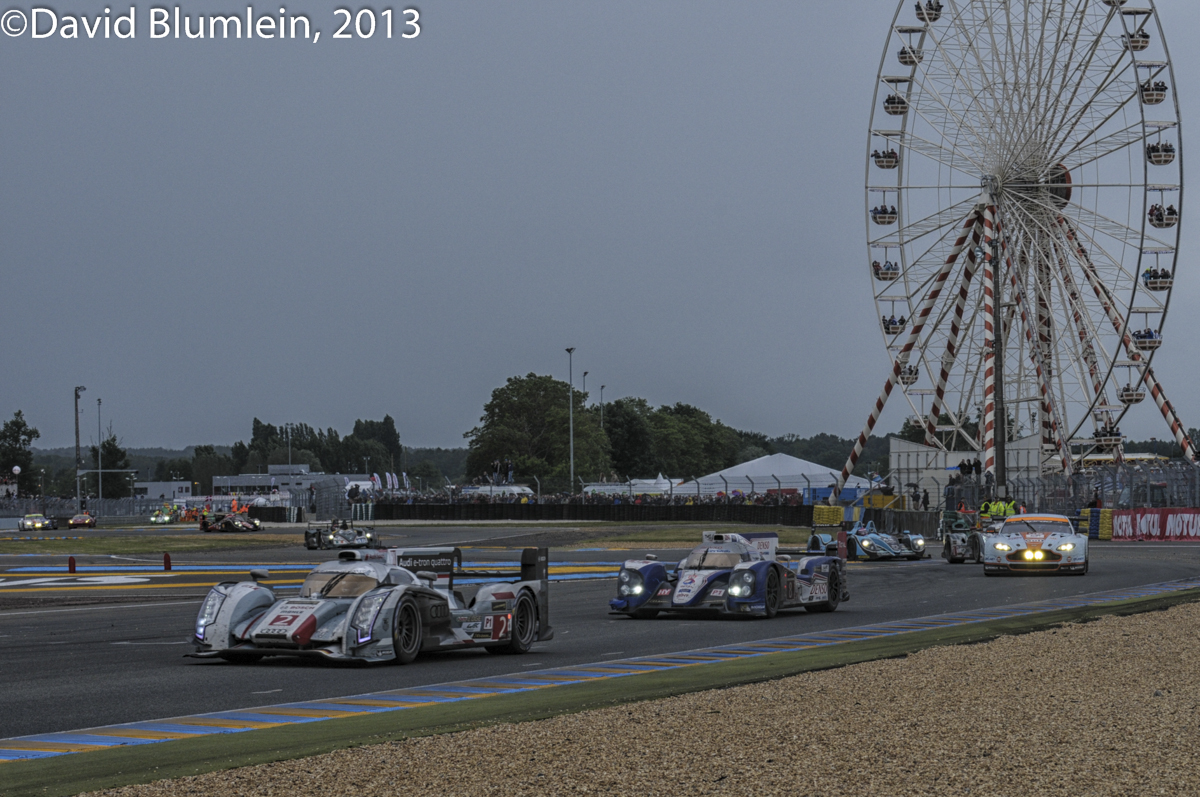

The sudden rain showers can catch out the best.

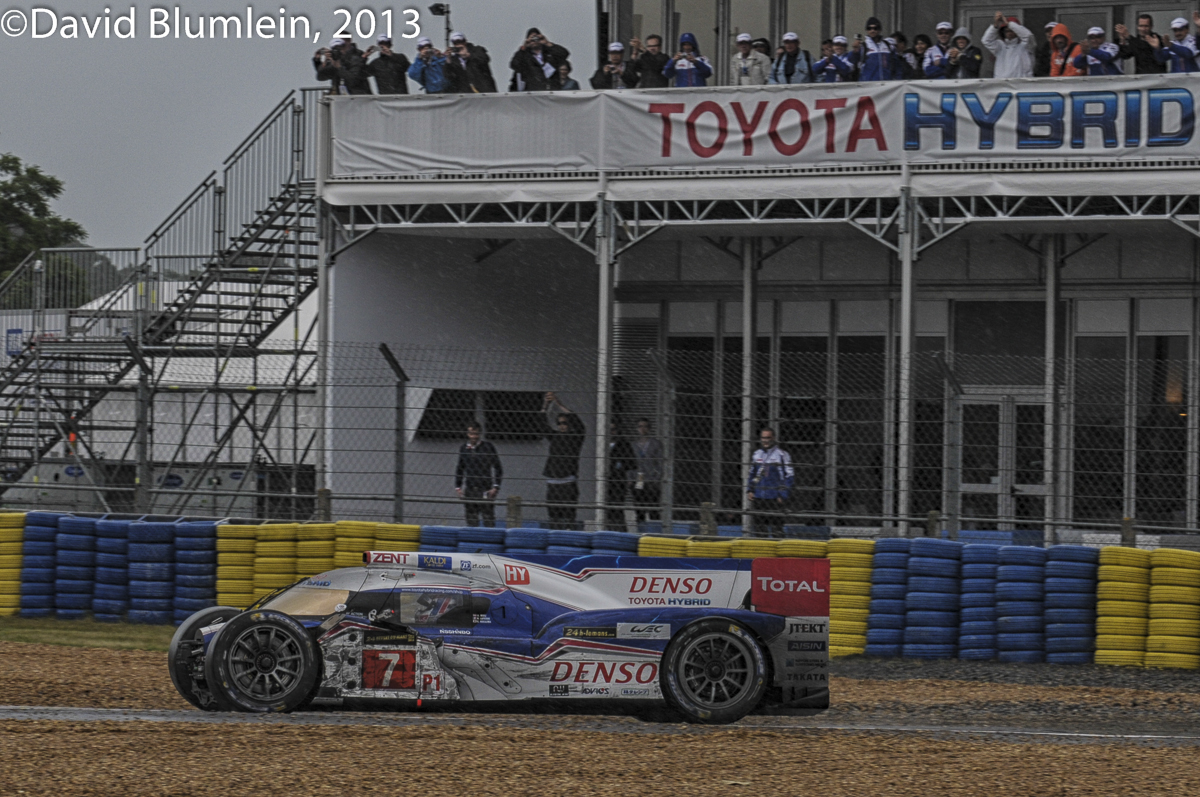

But to cross the line after 24 hours is worth all the effort:

David Blumlein July 2013