It does not take long in this business to spot those who are on the pace, on track or off, with or without a stopwatch. Thirty plus years ago I first met Alan Lis, a writer who was, and is, definitely in the “on the pace” camp. A while back Alan conducted interviews with some of those involved at the heart of the dramatic 1969 Le Mans 24 Hours. 50 years have passed since that famous race but those who witnessed it either on track or via the television or media still recall the excitement of the finish. A once in a lifetime experience. Alan has generously shared his work with us here, Merci beaucoup!

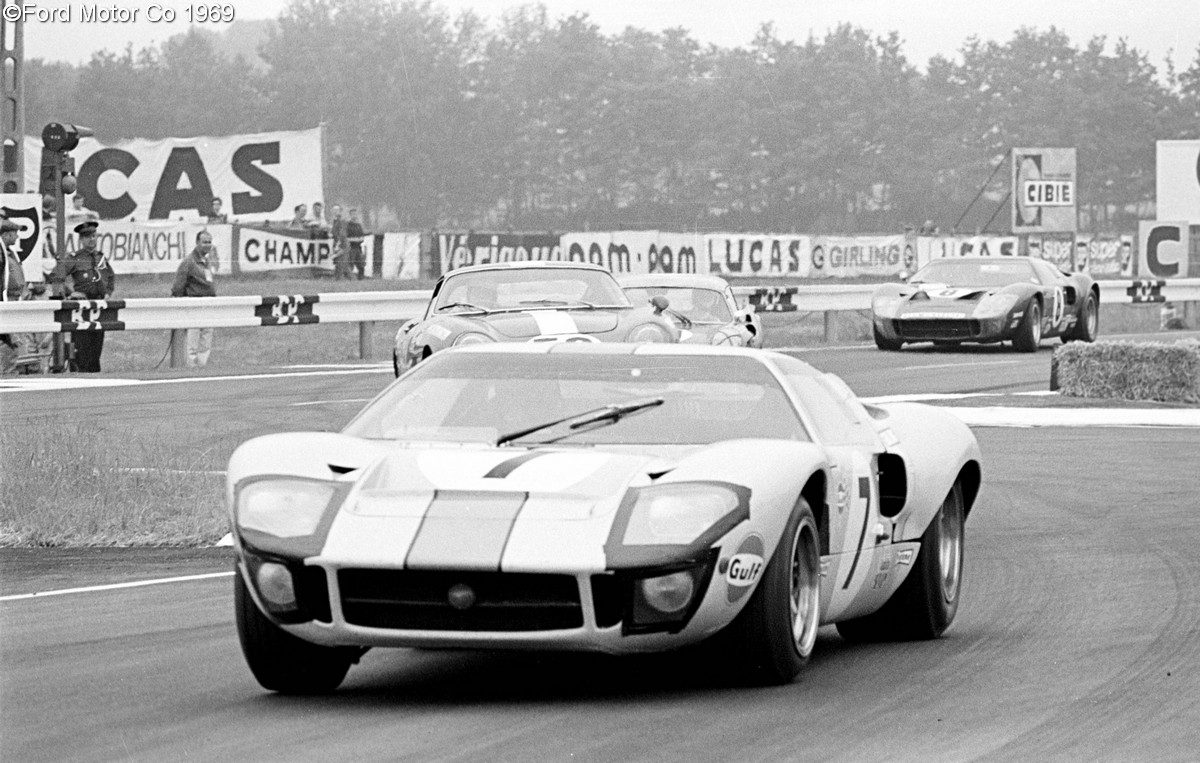

The 2019 24 Hours of Le Mans marks the fiftieth anniversary of the most famous finish in the history of the Grand Prix d’Endurance. Against the odds, the JW Automotive Engineering team Ford GT40 driven by Jacky Ickx and Jackie Oliver won by a narrow margin of just over 100 metres (or 1.5 seconds). Ickx having fought out a frenetic duel for victory with the sole surviving works entered Porsche 908 driven by Hans Herrmann for the final three hours of the race.

John Horsman – Chief Engineer – JWA Automotive Engineering

“The GT40s started thirteenth and fourteenth on the grid, which was a very lowly position for us. The times were set in the first practice on the Wednesday and we did not go to Thursday’s practice; there was no point. The car was not going to go any faster and there was no interest in improving our grid position. The car knew its own way around the circuit, so we had two days to prepare, we were nicely rested and ready for the race on Saturday.”

“Of course, Jacky Ickx made his famous walk across the road, which he hadn’t told us about so that was a surprise. Hobbs got away to a very good start and got through the John Woolfe accident before it happened, Jacky was at the back of the field and had to thread his way through but had plenty of warning. So, both our cars got through that first lap problem unscathed.“

“The Hobbs/Hailwood car led the Ickx/Oliver car for at least half the race until they had a problem with a brake caliper. A wheel weight had been improperly placed, hit the bridge pipe on the caliper and broke it. Unfortunately, we didn’t find the problem at the first stop so the car had to stop again when the problem was fixed but that dropped number 7 back behind number 6. Otherwise Hobbs and Hailwood would have almost certainly have won the race. They should have won because they were about half a lap ahead at that time.”

“Early in the race the Porsches were dominant but as time progressed, we found ourselves in better and better positions eventually third and fourth. The 917s fell out and two 908s collided on the straight, which was very convenient for us. At the end there was just the Larrousse/Herrmann 908, which had been delayed by a wheel bearing failure early on, and was catching us fairly quickly.”

“In fact, they caught us a little quicker than expected but our team manager David Yorke was very calm and collected and made a very good move at our second to last pit stop when we were still in the lead. He instructed the mechanics to lift the tail, go over everything, check the oil, check the water; we put new brake pads in even though they were not actually required at that time.”

“David could see a big battle coming up and wanted to give the drivers the best tool they could have for the oncoming battle. Normally we got through a pit stop as fast as possible to save time but David decided to take an extra thirty seconds to have good look over the car and check everything, do a ‘fifteen-thousand-mile service’ on it and off we went again. By which time of course the Porsche was much closer. But then the race was won on brakes and we had the equipment to do it. The Porsche had a warning light coming on but it proved to be a false warning. Of course, there’s a difference in hurtling down to Mulsanne corner with a warning light on not knowing whether you are going to have brakes or not. That was very definitely our finest hour with the GT40.”

David Hobbs – Driver JWA Automotive Engineering Ford GT 40 Car number 7

“Le Mans 1969 was the most unfortunate and biggest near miss of my career. I made a terrific start and Ickx did his famous slow walk. I rocketed off and got through White House before the accident. That put me an instant lap up on Ickx and Oliver and that was how we stayed until about five o’clock the next morning.”

“In fact, neither of us were doing terribly well, we had qualified well down and we were all running along at about the same speed. With David Yorke managing the team we were stuck on a fixed lap time. The Porsches were well ahead of us but in the middle of the night – at about 3am – two 908s overtook me on the straight and pulled away. It was pitch dark and I saw these four tail lights disappear around the kink followed by an immediate flash of white headlight and almost instantly after that a huge glow of gold and red fire. Obviously, I put the brakes on but by then I was right in the kink myself. As I went through I found the road completely blocked with flames and smoke and dust and crap everywhere. There was no point in swerving, where the hell are you going to swerve to? I burst through this lot and out the other side and there’s half a Porsche tumbling end over end down the middle of the track. Then out of the Porsche pops the driver and he tumbles down the road. I didn’t know whether to run over the driver or the car but in fact I didn’t touch either in the end.”

“It happened to be my in lap, so I came into the pits and said to Mike, “Jesus there’s been a shunt, the road’s all f**ked up and some bloke’s been killed …” What had happened was that Udo Schutz and Larrousse had touched, Schutz car had spun into the inside of the kink, hit the guard rail and broken in half, leaving the engine and gearbox blazing attached to the rail as him and the cockpit had bounced down the road also on fire and had finally come to rest about two or three hundred yards further down the road. He apparently bounced out and was absolutely fine. He always was a bit overweight which had perhaps made it easier for him to bounce down the road.”

“On my next stint came the real killer for our hopes, we were still leading our sister car and as I approached Mulsanne corner the brake pedal went to the floor. I did some rapid pumping but it was all too late and I shot down the escape road. I had do a three-point turn and drive slowly back to the pits. When the door was opened, David Yorke was there and I said “The brakes have gone completely”. He said, “It’s the pads. You’re about due for a change so it must be the pads”. I said, ” No, it’s more than pads” but he wasn’t having it. “No, its the pads. You drive I’ll team manage…”. So, they changed all the pads put the fuel in and sent me off. When I got to the end of the pit, I nearly ran over the marshal with the flag because the car wouldn’t stop. So now I’m committed to an 8½ mile slow lap… When I came back in, they took the bodywork off and all the wheels off. On those Girling calipers there was a bridge pipe from one side of the caliper to the other and the Firestone tyre fitters had put wheel weights on the inside of the rims as opposed to the outside. The JW people knew there was very little clearance between the wheel and the caliper and the Firestone engineers had been warned about it but it had happened anyway. One of the wheel weights had chipped a little hole in this brake pipe and the fluid had drained away. The pipe was changed the pipe, the system was bled and everything was put back together and off we went again but now of course it’s the other way around and Ickx is ahead.”

“Towards the end of the race of course it comes down to him and Hans Herrmann who are having this incredible duke out for first and second and Mike and I are bowling along in third. If it hadn’t been for that bloody wheel weight, we would have been rolling along in first and these two blokes would have still have had their titanic battle but it would have been for second.”

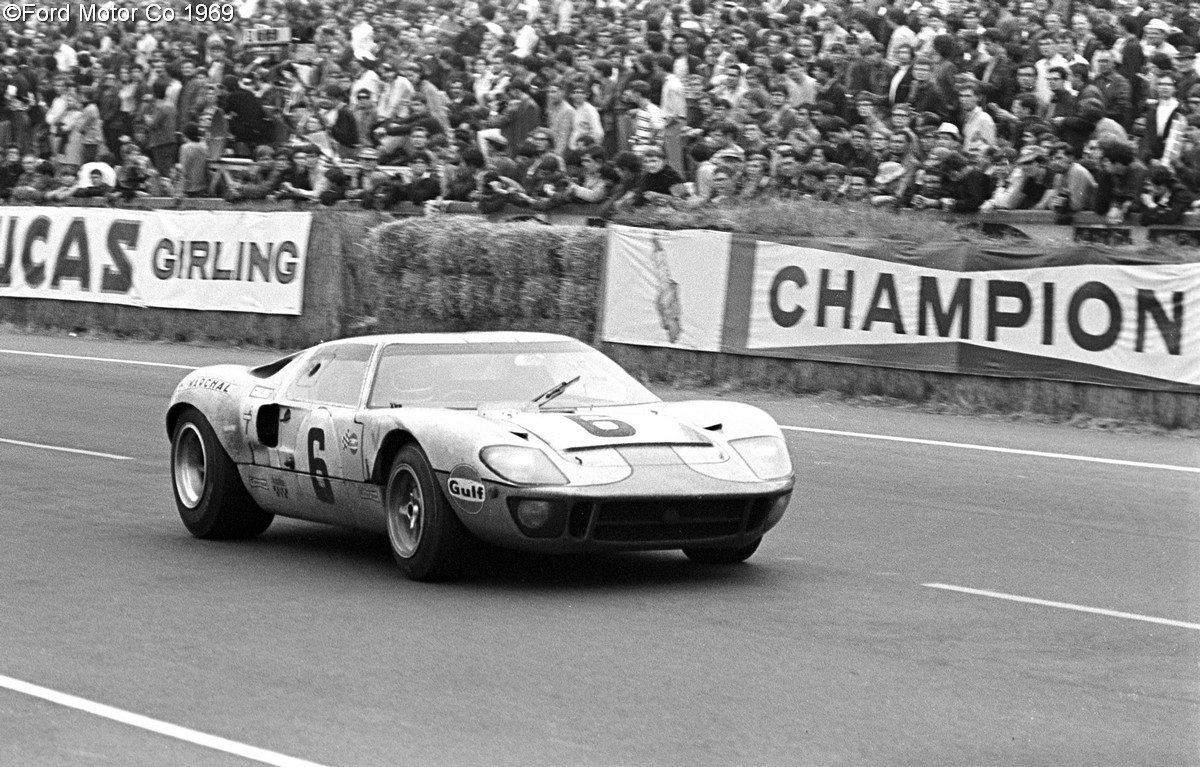

Jacky Ickx – Driver JWA Automotive Engineering Ford GT 40 Car number 6

“As far as the spectators were concerned the 1969 Le Mans 24 Hours was the most famous race. The race was very exciting, especially the last three hours. Just by luck the two leading cars were running exactly the same speed at the same time for the last three hours. We were making pitstops for fuel and tyres more or less on the same lap. So, we were able to run close together for three hours. One a little bit in front, but neither able to pull away from the other. The more that time passed the more we knew that the race was going to be decided either by a mechanical problem or on the last lap.”

“It was at a time when drivers were realising that it was nice to go motor racing but also that you needed to survive. Life is too short to die in a racing car. In the fifties and sixties there were so many bad accidents, fatal accidents, that it appeared that we were doing things sometimes that were completely stupid. For many years in the sixties we drove without seatbelts. They only began to appear around that time. It only became mandatory later. There was still a legend saying that it was better to be thrown out rather than trapped in the car. If you say that today you would get a giant laugh because everybody knows that it’s not the case. The problem of Le Mans in those days was that you had to run and jump into the car. To be the first one into the first corner you had to forget about the seatbelts until you got to the straight and then you had to try to put the belts on while you were accelerating on the Mulsanne. That was why I started the race by walking to my car but for the last few metres I had to hurry up because the other cars were starting and so I had to run a little bit.”

“At the end of the race Porsche chose to put Herrmann in for the last stint because he had more experience but I think he was maybe too cautious. I have always thought that maybe it would have been more difficult if Larrousse had stayed in the car.

“There was a lot of strategy, I remember, especially on the last two laps. We knew that the flag came down at four o’clock, so on what we thought was going to be the last lap he started down the straight first and I over took him by slipstreaming by as late as I could going into Mulsanne corner and I knew that he could not overtake me after that. But unfortunately, when we reached the clock at the finish line there was still thirty seconds to go so, we had to do another lap. The extra lap was pushing both me and him to the limit of fuel so we had no guarantee to finish.”

“Of course, having done the trick on Mulsanne on the previous lap he knew that he didn’t want to start the straight in front of me. So, I was first and he wouldn’t pass of course. I had to slow down and down until I was going at maybe only one hundred kilometres an hour before we got to the restaurant. I think I got so slow that maybe he felt that I was running out of fuel. As we got to the restaurant he must have thought “That’s it now I go”. I was watching in the mirror and suddenly he went past me. I jumped into his slipstream and stayed there. We both increased speed and after the kink I used the slipstream and passed him on the inside.”

“It was a time when fairness when you were driving a racing car meant something. He wouldn’t have done anything like the things you see today. That didn’t exist. It was very important for me to pass at the end of the straight because he was faster down the straight but slower on braking. On lap times we were equal but I knew from the experience of the last three hours that I had to be in front of him at that point because he could not overtake anymore after Mulsanne corner.”

“When we reached the finish, I was very happy and the team were frantic, Oliver and everyone in the pit was very, very excited, it was unbelievable. The race was very well covered on TV and people were able to see the last three hours and especially the last hour live. I think maybe it was one of the first years that they used aeroplane with a TV camera onboard. It was a transport plane and they opened the rear door and pointed the camera down at the track. That plane was following the cars round the circuit and it was the first time that people watching the TV were able to see the race so completely. I think that is why so many people remember it so well.”

JWA team principal John Wyer was unable to attend to race, in the evening Ickx received a telegram from him bearing a single word: “Manifique!”

Alan Lis, July 2019