Racing has lost one of its true “originals” with the death last week of 89 year old former Texas chicken farmer, Le Mans winner and Cobra entrepreneur, Carroll Shelby. While he wasn’t the originator of the Ford Motor Company’s “Total Performance” program that brought the Detroit giant foursquare into motorsport in the 1960’s, it was he and his Cobra which arguably expanded Ford’s competition efforts beyond the world of NASCAR into the international scene that included Le Mans and eventually Formula One.

A Second World War Army Air Force instructor pilot, Shelby was one of the many Americans who came out of the Southern California road racing community in the immediate years following the conflict’s end; a cadre that included men such as Phil Hill, Richie Ginther, Masten Gregory and Dan Gurney among others. Having established himself as part of the winning elite behind the wheel of various Ferraris and Maseratis, he moved to Europe in the latter part of the 1950’s, driving in both Formula One and in sports cars.

And, although his F-1 career was less than spectacular, his two seater results were more than impressive, including his 1959 Le Mans triumph as a member of the John Wyer led Aston Martin factory team. Unfortunately, it was not long after that he began to experience the heart issues which would force his cockpit retirement and which would eventually lead to a heart transplant that extended his life for more than 20 years.

While his heart have made him quit as a driver, he didn’t quit the sport. In 1962, having learned that the Bristol engine supply for the AC Ace had dried up, Shelby set out to make a deal that would replace that powerplant with a V-8 from one of Detroit’s big three. Coming to an agreement with AC was the easy part, convincing the “Motown” executives was not.

Turned away at both General Motors and Chrysler, Shelby found a much better reception at Ford which saw the opportunity being offered them and said “yes.” Thus was born the Cobra “powered by Ford” in the form of its small block eight cylinder used in its Falcon compacts and medium sized Fairlane. The Cobra proved to be not just a race winner, but a performance image sales leader that boosted Dearborn’s profits throughout its entire car range.

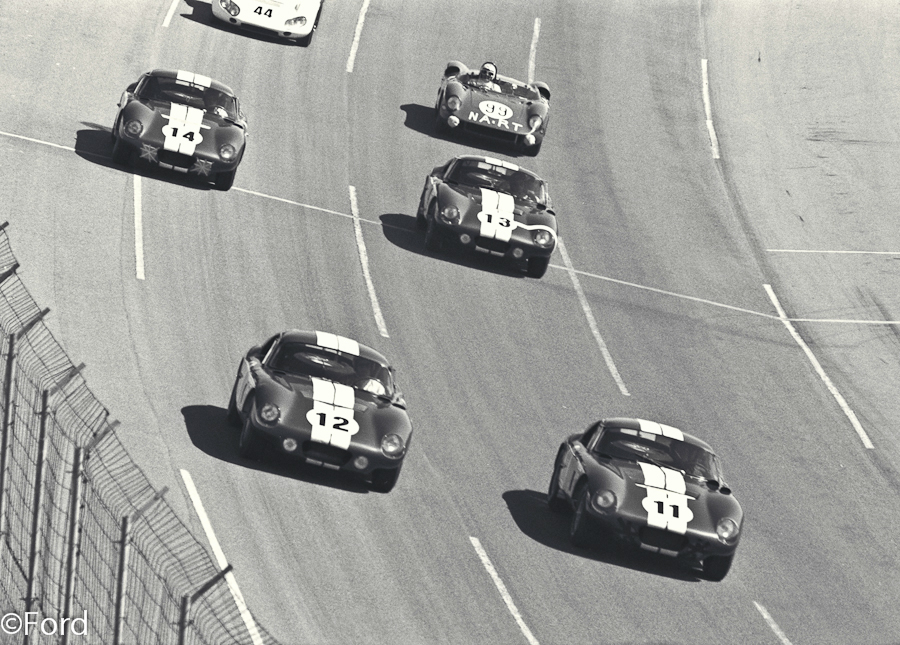

Despite its crudeness, the reborn Ace was more than up to the job of humbling its Corvette competition, claiming two straight United States Road Racing series crowns in 1963-64 against not only Zora Duntov’s two seater, but the Ferrari and Aston Martin entries that accompanied it. More importantly, having lost out to the Italians through a bit of chicanery on Enzo Ferrari’s part in 1964, Shelby’s Cobras took the World Manufacturer’s title for Ford in 1965 with relative ease.

By then, though, Shelby was deeply involved in not only the GT40 project, but also in transforming the hot selling Mustang into a proper racing car in the form of Shelby’s California-produced GT350 version which dominated its class in North American amateur competition.

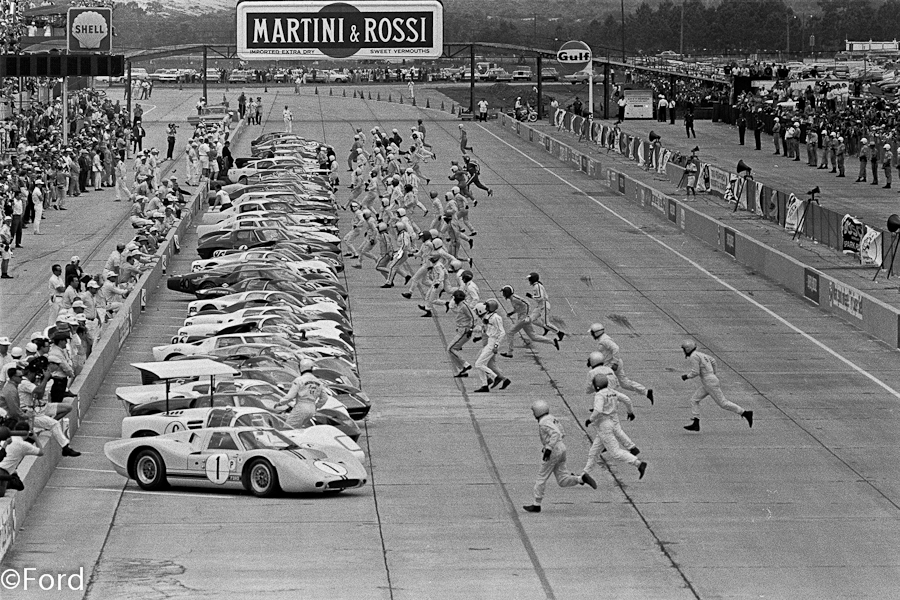

Despite problems, it would be Shelby entered Mark II and Mark IV GT40s that would claim the honors for Ford at Le Mans in 1966 and ’67, those triumphs leading the FIA to kick the Americans out of the Makes championship of which the Sarthe was a part immediately thereafter.

With end of the factory GT40 program (Wyer-entered five liter Mark I examples would embarrass the FIA and the French by winning again in 1968 and ’69), came a new domestic beginning for Shelby in the form of the Trans-Am sedan series which again pitted the Mustang against GM’s Camaro and AMC’s Javelin for “Pony Car” superiority, again on the track and in street sales.

For Shelby the Trans-Am was a mixed bag. After winning the title in 1967, his team’s fortunes declined despite some individual race successes, as Camaros of Roger Penske and Mark Donohue claimed the Trans-Am crown in 1968 and ’69, the latter season being Shelby’s last in the championship.

Indeed, it likewise marked the end of his relationship with Ford, as the company was forced to leave motorsport during the 1970’s to deal with the increasingly burdensome government imposed emission and safety regulations. Later in life, after a brief association with Chrysler, he would return to Ford, not as a racer, but rather in the role of someone who lent his name to various of Dearborn’s high performance street vehicles.

In many ways, Shelby’s true talent, aside from his driving, was as a self promoter, which might seem at first glance to lessen his value and image within the sport and the automotive industry, but which on more sober reflection is not so because in his self promotion Shelby over and above his racing successes left us with a desire for high performance street cars that has continued to this day despite all attempts to quench it. For that he will remain always a giant.

Bill Oursler, May 2012