The Audi R8C was far too new to stand a chance at Le Mans even if the field had not been as packed with contenders for victory as it proved to be in 1999. There is one certainty when running in the 24 Hours at La Sarthe, if there is a weakness it will be found out. The intense test programme post Pre-Qualifying did not reap much in the way of lap time improvements and the transmission still gave much cause for concern. The project needed months not weeks of development to realise its obvious potential, the speed was good on the Mulsanne at 217mph but handling issues elsewhere meant that time was lost.

One area that Audi had employed lateral thinking to get an advantage over their competitors was the ability to change the entire transmission in next to no time on the R8R. Dry-break couplings were fitted to engine, clutch and gearbox oil cooler fluid pipes. Special tools were made to facilitate removal of the bellhousing, all of which was possible because the R8R’s rear wing was part of the tail section rather than being attached to the gearbox. During the run up to the race a practice run was undertaken and the whole rear end of transmission and rear suspension was replaced ready to get back on track in around five minutes!

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this arrangement was that the press almost completely missed it. Even the doyens of the Le Mans’ Media Tribe, Paul Frère and Jean-Marc Teissedre, only noted the speed of the R8R transmission changes during the race but did not enquire as to how this was achieved. Perhaps they did and were fobbed off with bullshit. To be fair there was plenty of excitement going on with flying Mercs and crashing Toyotas and the BMWs. My source for this and other technical information is the excellent autobiography from Tony Southgate and he would know.

Another improvement to the transmission came with the adoption of the Mega Line pneumatic gearshift for the R8R. This system allowed the drivers to keep both hands on the steering wheel at all times, helping with cornering, and there was a dramatic reduction on the wear on the dog-rings in the gearbox, greatly improving reliability over a long distance race.

The 1999 edition of the Le Mans 24 Hours was something of a high water mark for the participation of manufacturer backed teams in pursuit of outright glory. No fewer than four other factories joined Audi in the hunt for victory, 15 cars in total. BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Nissan and Toyota were all serious contenders for victory, only Porsche was missing and they would not be back for a generation.

Pole position was grabbed by Martin Brundle in the Toyota GT-ONE, scorching round in 3:29.930, meanwhile the R8Cs were struggling, the best that #10 could manage was 20th and 3:42.155, #9 was timed at 3:45.202 which meant a further three places back on grid.

No matter what problems the Audi Sport UK were enduring they were not as bad as some others were experiencing. Eric van de Poele destroyed his Nissan early on Wednesday injuring his back seriously. The following evening Mark Webber became airborne in his Mercedes-Benz CLR, a feat he repeated during Saturday’s Warm Up, scratch two contenders from the race.

The situation on the other side of the Audi pit boxes was far more promising. The R8R pair got on quietly during Practice and Qualifying with Capello’s 3:34.891 being good enough for 9th place, Biela just half a second behind. A good result seemed within the team’s grasp, though the message came down from the Board, a podium was the minimum that would be accepted or else…………………….

I have worked for teams at Le Mans that have had problems with the car right from the start, it is a nightmare situation that can only end in pain, with no prospect of redemption or salvation, so I can sympathise with the hard working crew of Audi Sport UK. #9 was in after half an hour to have the suspension checked, then, just before 20.00, the car stopped at the entry to Les Hunaudièrs, the differential had broken, the car was the third retirement.

#10 lasted but 20 minutes before stopping to change the gearbox, a process repeated around midnight. The agony continued till 8.20 on Sunday morning when the gearbox failed again stranding Perry McCarthy out on track, ending the Le Mans’ career of the Audi R8C.

The Audi R8C was never seen again in competition, all resources were focused on developing the new 2000-spec car, the R8. However, the R8C did contribute substantially to the next Volkswagen Group endurance coupé, the Bentley Speed 8. Also designed by Peter Elleray and built at RTN, the Bentley beat the rest, including the legendary Audi R8s, to win Le Mans outright in 2003.

The other side of the Audi operation ran much more smoothly with only minor niggles afflicting #8 R8R. All the misfortune seemed to flow towards #7 which had no less than four transmission replacements but with the quick change system paid off, with each new gearbox being fitted in around five to ten minutes rather than the 50 minutes taken each time by the R8C. #8 ran strongly in the top five for most of the race, things were going to plan.

Both Audis benefited from the retirements of other contenders, the two top Toyotas each had a big accident during the night and engine failure accounted for the Nissan. As to Mercedes-Benz, the catastrophe forecast by many happened just before 21.00 when, watched by the world on television and endlessly replayed, Peter Dumbreck’s CLR somersaulted into the trees at almost the same point where Webber had crashed on the Thursday. Mercedes-Benz has not been seen near Le Mans since nor are they expected back anytime soon.

The race had one final twist in the tale. The BMW of Lehto, Müller and Kristensen had led from almost the first hour and the trio had a cushion of three laps over their sister car. Then the roll bar broke and jammed open the throttle pitching JJ into the barriers at the Porsche Curves and out of the race. This misfortune elevated the #8 Audi to 3rd and the #7 to 4th, which, considering the situation Mercedes were enduring, was a good performance. Could they hang on?

The answer was yes, to the relief of the Boss Dr. Ullrich. Third place went to #8 driven by Frank Biela, Emanuele Pirro and Didier Theys, they were five laps down on the winning BMW. Fourth, some 14 laps adrift of their sister car, was #7 with Michele Alboreto, Dindo Capello and Laurent Aïello on driving duties. The result was enough to get the green light for a new car in 2000, the Audi era was about to commence.

Third and fourth places at Le Mans was not quite the end of the story for the R8R. While a completely new car would be unveiled for the 2000 season, the R8R would act as a test bed during the rest of 1999 for proving the components such as engines and transmission plus work on aerodynamics. The engine had performed faultlessly during the race, as we have come to expect from the work of Ulrich Baretzky’s department. Detailed improvements in power and weight reduction would lead to a major development in 2001 with the introduction of FSI direct injection technology.

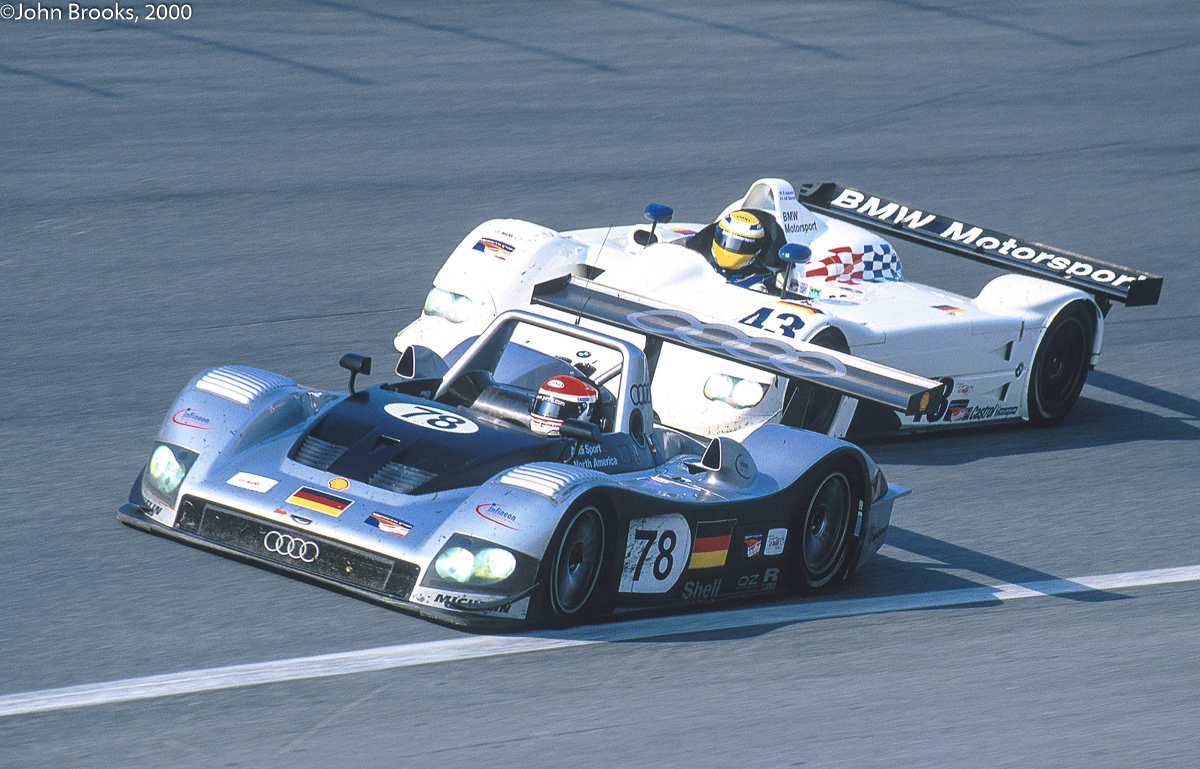

There would be two more races for the R8R in 2000 in the American Le Mans Series rounds at Charlotte and Silverstone, while the new R8 was kept in reserve for the Le Mans 24 Hours. A podium place in the UK for Allan McNish and Dindo Capello was an appropriate way to mark the end of the road for the R8R.

Audi’s course was set for the next 17 seasons, racking up titles and victories no matter who was the opposition. The pit lanes and paddocks of the endurance world will feel strange in 2017 with the Four Rings.

John Brooks, December 2016