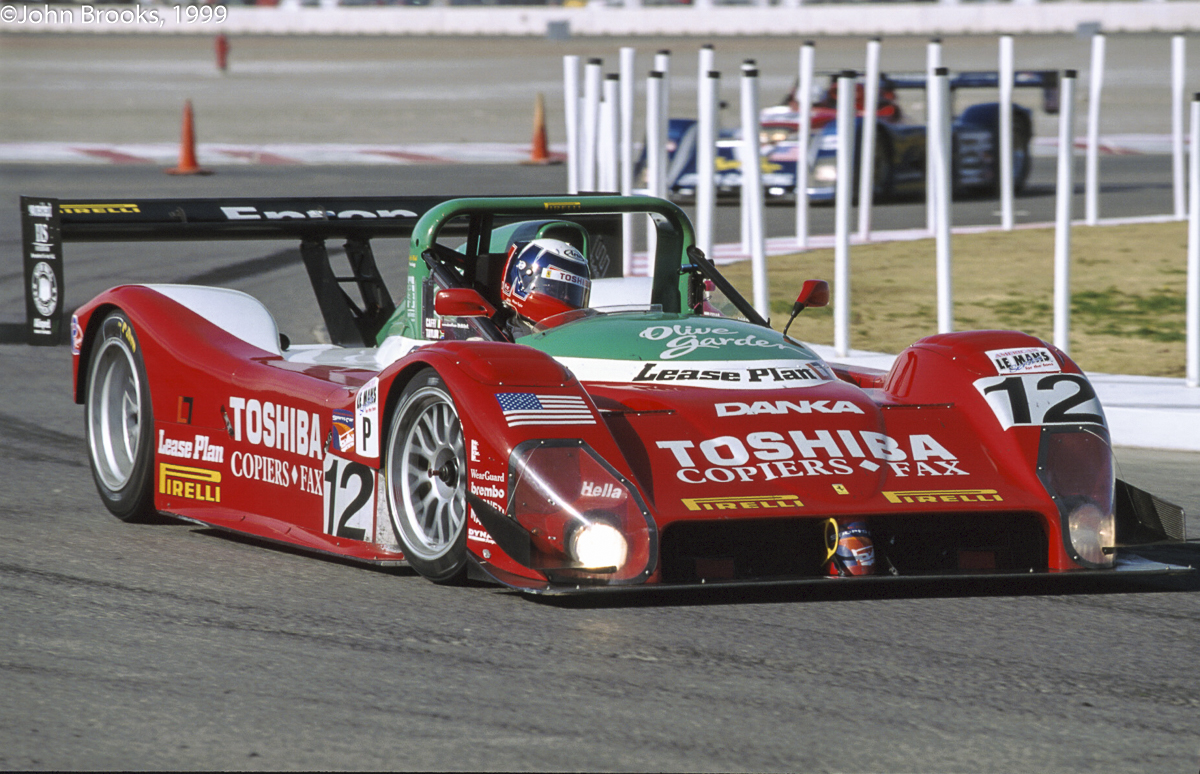

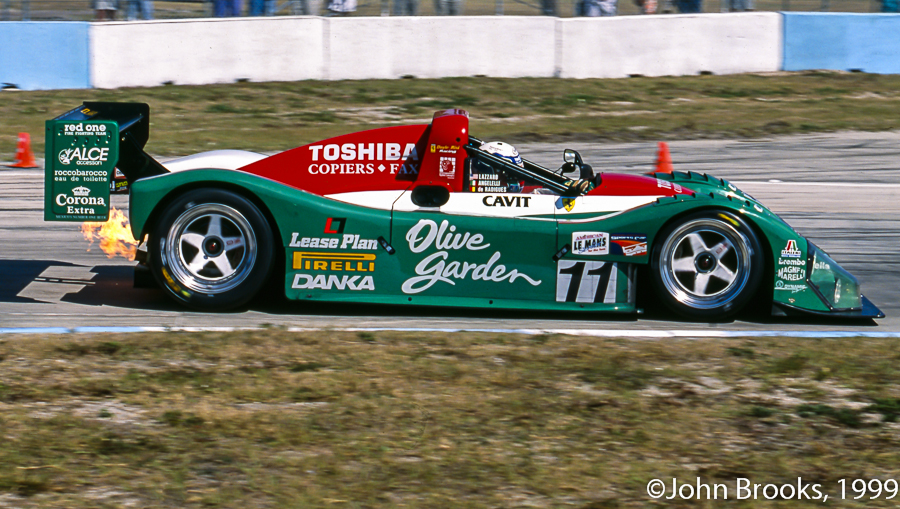

There can be no doubt that one of the truly great racers that emerged from Maranello in the ]ast two decades is the Ferrari 333 SP. Elegant proportions and a V12 wail, it has everything that a classic Ferrari must possess. One of the leaders of this exclusive pack is #012 – here is the legend as seen from the inside. Follow this tale of redemption and rebirth……..

John Brooks, May 2019

Fredy Lienhard, Jurgen Lassig, Piero Lardi Ferrari and the HORAG crew at Maranello picking up Chassis #012 in early 1995.

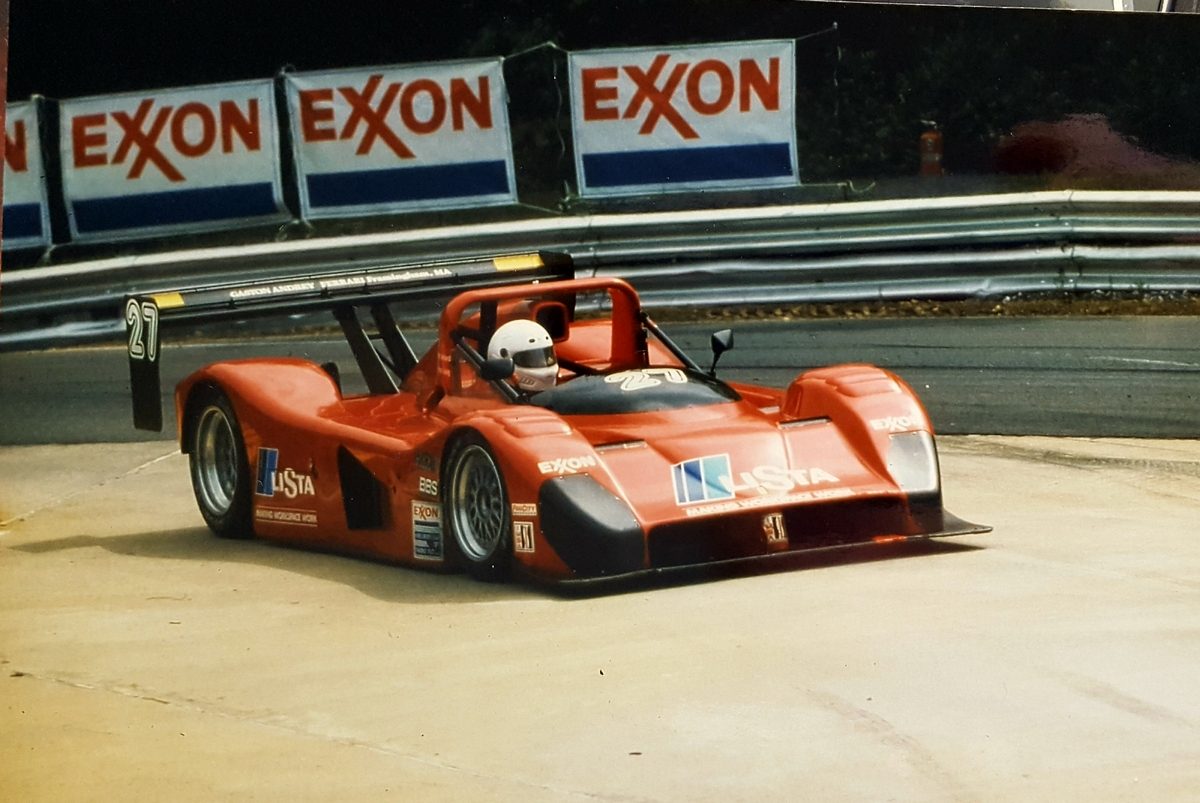

In April 1995, Fredy Lienhard came down south to Georgia to race his new Ferrari 333 SP in the IMSA race at Road Atlanta.

March 1995 – Swiss Championship race at Hockenheim Germany, which Fredy would win in the first event for the car.

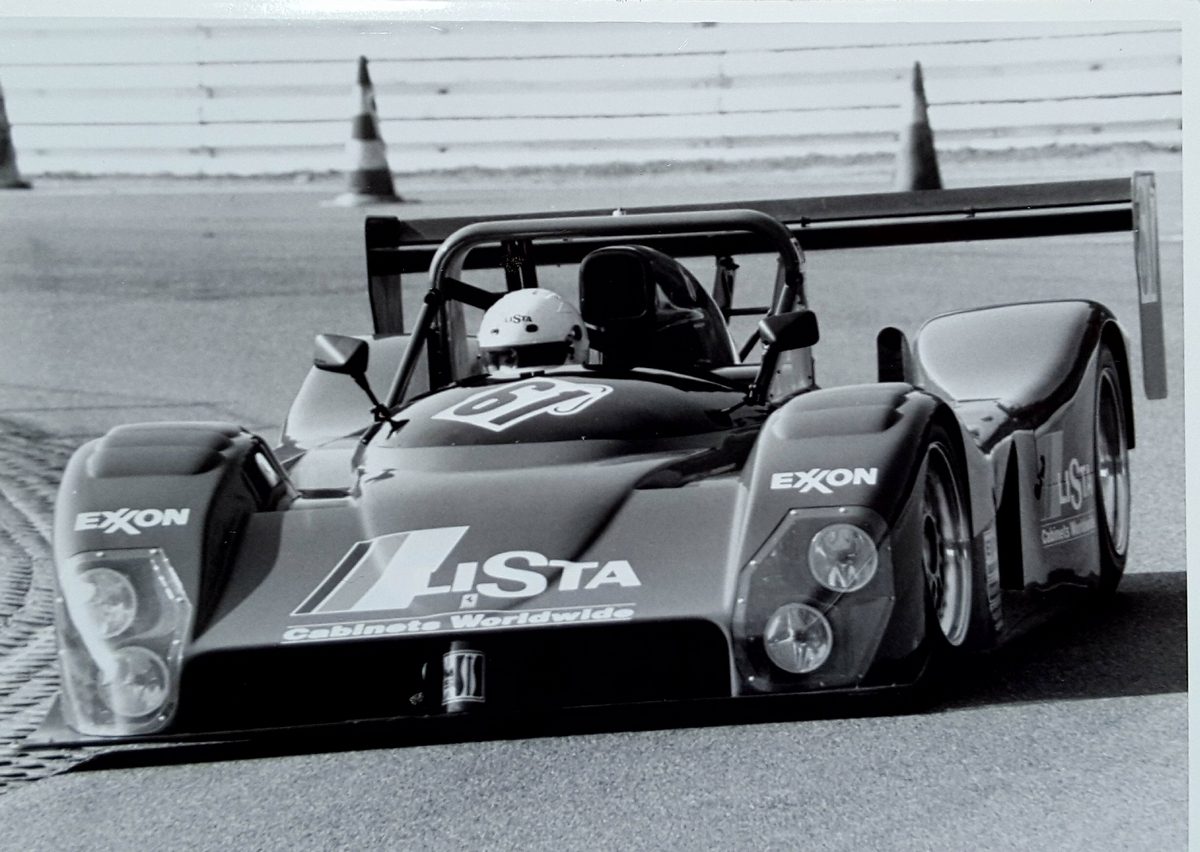

Fredy had purchased a new car, chassis #012 and had raced the vehicle the month before in March, at a Swiss championship round at Hockenheim in Germany, and won with it. Fredy was a Swiss Industrialist, who loved racing, and race cars as an adjunct to his business, using the platform as a promotion for his customers, and as advertising for his company LISTA, which made industrial storage equipment, tool boxes, and office furniture.

Chassis #012 gets pit service during practice for the IMSA race at Road Atlanta in April 1995.

This was basically the second season of the Ferrari 333 SP and the World Sports Car (WSC) formula in IMSA. There were four 333 SPs entered with their main opposition coming from Dyson’s Riley & Scott pair, plus several other WSC cars, as well as a full field of GT cars. The race did not start well. After 14 laps there was a huge accident on the main straight right in front of the pits, involving ex-F1/Indycar driver Fabrizio Barbazza in the Euromotorsport Racing Ferrari 333 SP, Jeremy Dale in a Spice and several GT cars. The race was red flagged for 90 minutes to allow rescue helicopters to land on the track and take Barbazza and Dale directly to the hospital as they were both badly injured. To stand and watch this from the pits was disconcerting to say the least. Wayne Taylor who was driving our car (Moretti/ Doran 333 SP) was pretty upset about the accident. After the race was restarted, Gianpiero Moretti got in our car to continue, leaving the final stint for Wayne.

Chassis #012 rests against the wall at Road Atlanta April 1995. The car was deemed a total write off.

After 42 laps there was again a red flag stoppage due to another massive accident, this time on the back straight involving Fredy Lienhard, Steve Millen’s Nissan 300ZX and some other GT cars. The race was called “done” at that point, as it was going to get dark and take too long to clean up and repair the circuit.

The right side of the car did not look too bad after the crash about halfway through the race.

Moretti came into the pit and said, “I am glad this is over, let’s get out of here. It’s not fun racing when I see my friend Fredy up against the guardrail, and my friend Steve Millen being taken away on a gurney”.

Left side of chassis #012 after impact to left wall on Road Atlanta back straight.

In the ensuing confusion, Fredy, who was unhurt (except for what was probably a concussion, although he did not realize it at the time), walked back to the pits, got in his rental car, and drove to the Atlanta Airport. He said later, he did not even remember doing this. In any case, he got on a plane and flew to Zurich that night. The next day he says he felt terrible, experiencing dizziness and headaches. By this time IMSA was looking for all the drivers involved in the second accident and were somewhat perplexed that Fredy was nowhere to be found. The next morning, they tracked him down in Switzerland and called to make sure he was ok, and ask what had happened.

Ferrari 333 SP #012 was deemed a complete write off. The remains of the car were packed up and the chassis sent to Ferrari and Michelotto in Italy for analysis.

The HORAG crew with Markus Hotz in mid 1995 with the car which was now chassis “#012b” the replacement.

A new chassis was ordered from Ferrari. They provided a “replacement” chassis for #012, ostensibly keeping the serial number the same as the first one was “destroyed” (#012b). This was delivered to Hotz Racing AG, c/o Gaston Andrey in Massachusetts.

Led by Markus Hotz, a new car was built up at Gaston Andrey’s workshop in the USA by the HORAG crew in time for the IMSA Lime Rock race at end of May 1995. Here Fredy and Jurgen Lassig drove to a 5th place finish in the new chassis #012b.

There, a new car was built up by HORAG (Hotz Racing AG) for the IMSA Lime Rock round held at the end of May.

After Lime Rock in 1995, Didier Theys would co-drive with Fredy for the remaining schedule. Here they are in mid 1995, probably at Mosport event.

The car then ran the majority of the remaining 1995 IMSA schedule finishing all races in the top ten, then was shipped back to Europe.

#012b on track at IMSA Mosport in 1995. Fredy and Didier would finish 5th.

Didier Theys sits in #012b at Mosport in 1995

Fredy in #012b at Sears Point, August 1995, partnered With Didier they would finish 5th.

Fredy in 012b at the Donington ISRS race in 1997. The car had sat idle for most of 1996, only doing a shake down run at the Interserie in Most, Czech Republic. He and Didier finished 2nd at Donington.

Fredy and Didier on the podium after winning the ISRS event at Zolder Belgium in 1997 in #012b.

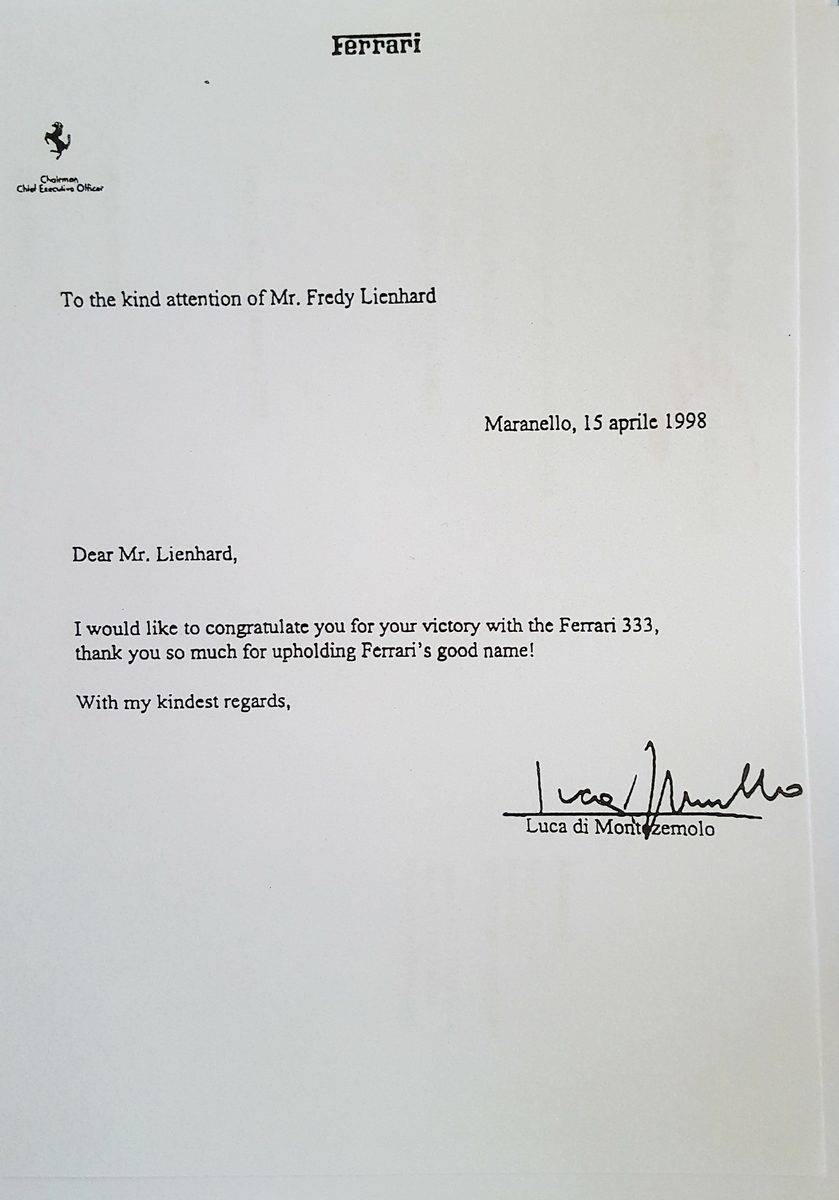

Fredy and Didier Theys win the first ISRS race of 1998 in #012b at Circuit Paul Ricard.

The race win at Paul Ricard, resulted in a letter of congratulations from Ferrari chief, Luca di Montezemolo.

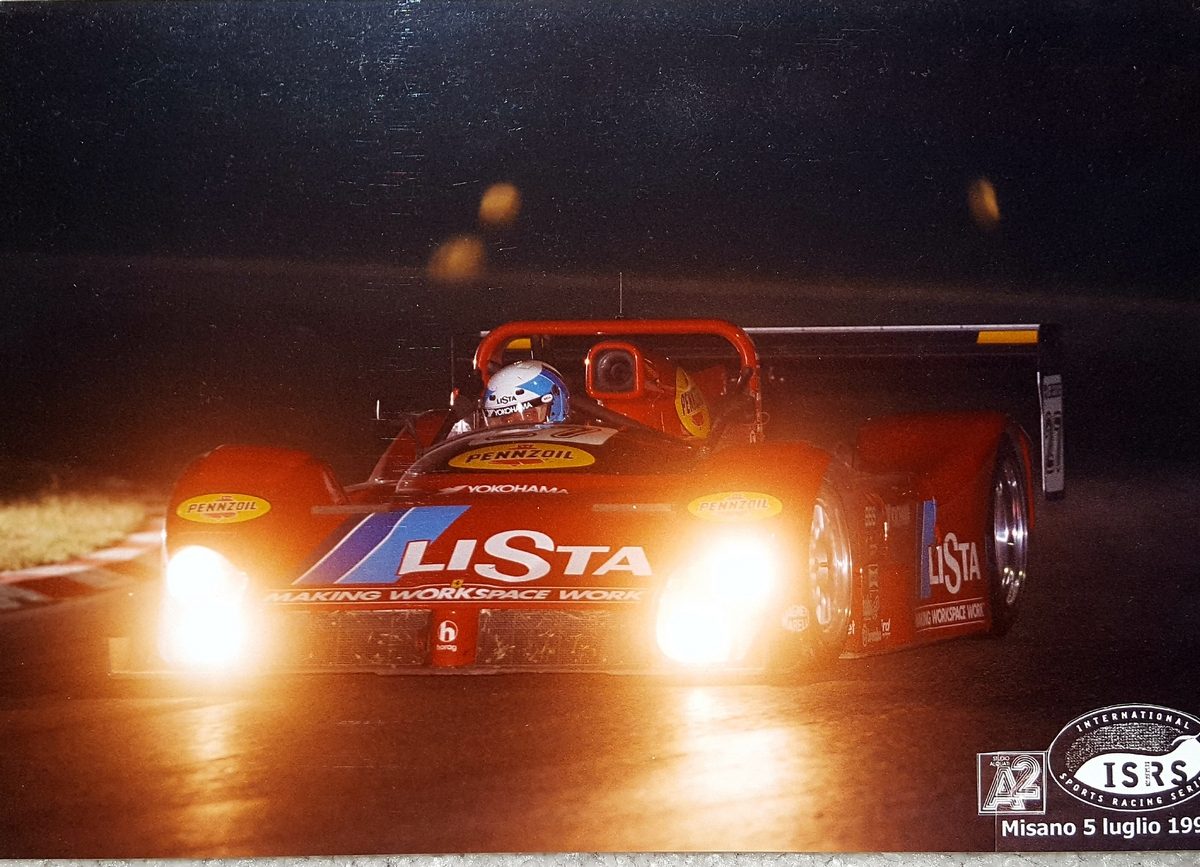

The Misano ISRS event was a night race, and Fredy and Didier scored 3rd place.

Fredy sits in the pits at the Nurburgring during ’98 ISRS race. The disappointing result was a DNF due to a gearbox issue.

There it ran one race in 1996, and most of the ISRS (International Sports Racing Series) over in Europe in 1997 and 1998. In early 1999 the car was sold to Ted Conrad. Fredy had meanwhile, bought new chassis (first #016, then #025) to run in IMSA in 1996, 1997 and 1998.

At the beginning of 2000 it became clear that the 4.0-liter Ferrari V12 would not be competitive under the latest rules package with power output controlled by air restrictors on the engine. The IMSA open rules under which the car had been designed and built, had morphed into the new FIA/ACO regulations. Ferrari refused to modify the engine for the new circumstances, saying this engine was not designed to run with such limitations. Ferrari teams, as early as 1999, had started to struggle against other cars with 6.0-liter engines, as, of course, a restricted 6.0-liter engine was better than a restricted 4.0-liter engine. The BOP (Balance of Performance) back then was just a varied restrictor on the air intake, nothing as sophisticated as today. Hence the 6.0-liter engines always had more torque, and the 4.0-liter lost horsepower due to the air restriction.

The man who came up with the FUDD (Ferrari-Judd) concept and implemented it, Kevin Doran.

Ferrari, never on the best of terms with the ACO or FIA in sportscar racing, refused to modify the engines or do the testing to make the engines run more effectively with the new restrictors. Teams started looking elsewhere at other cars or for other solutions in anticipation of the 2000 season.

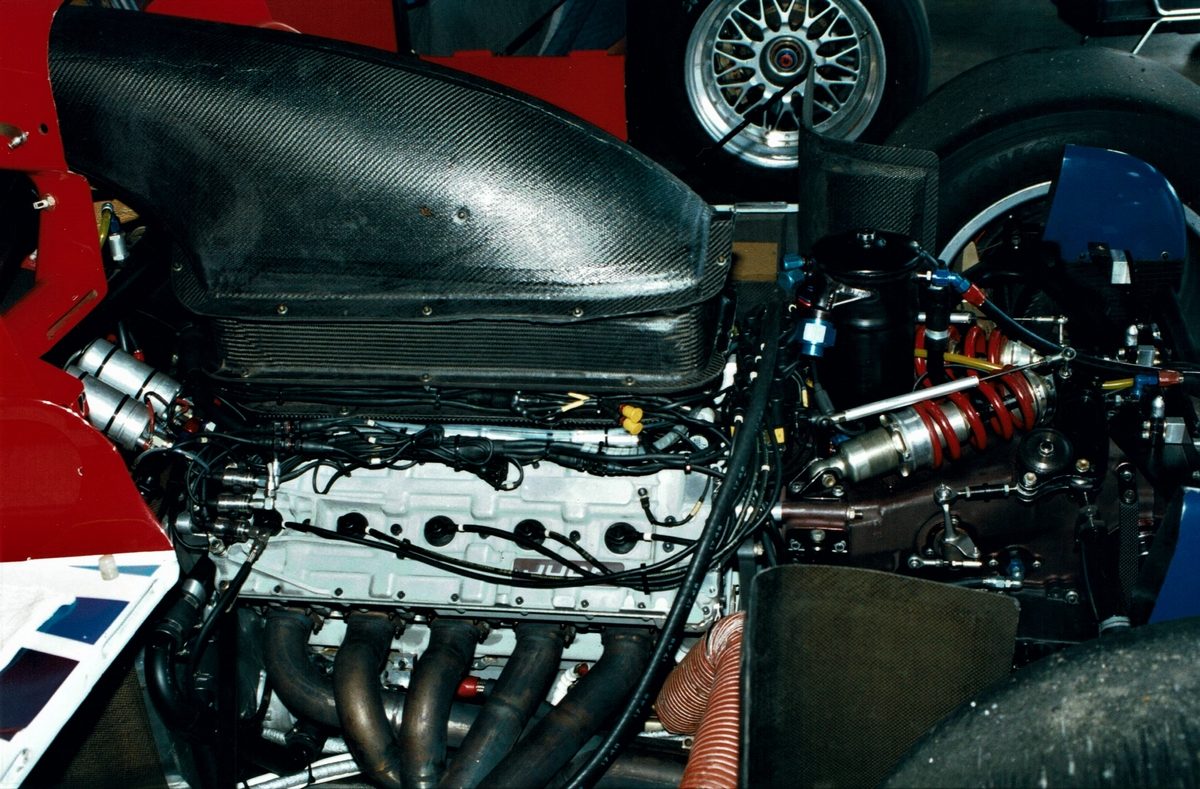

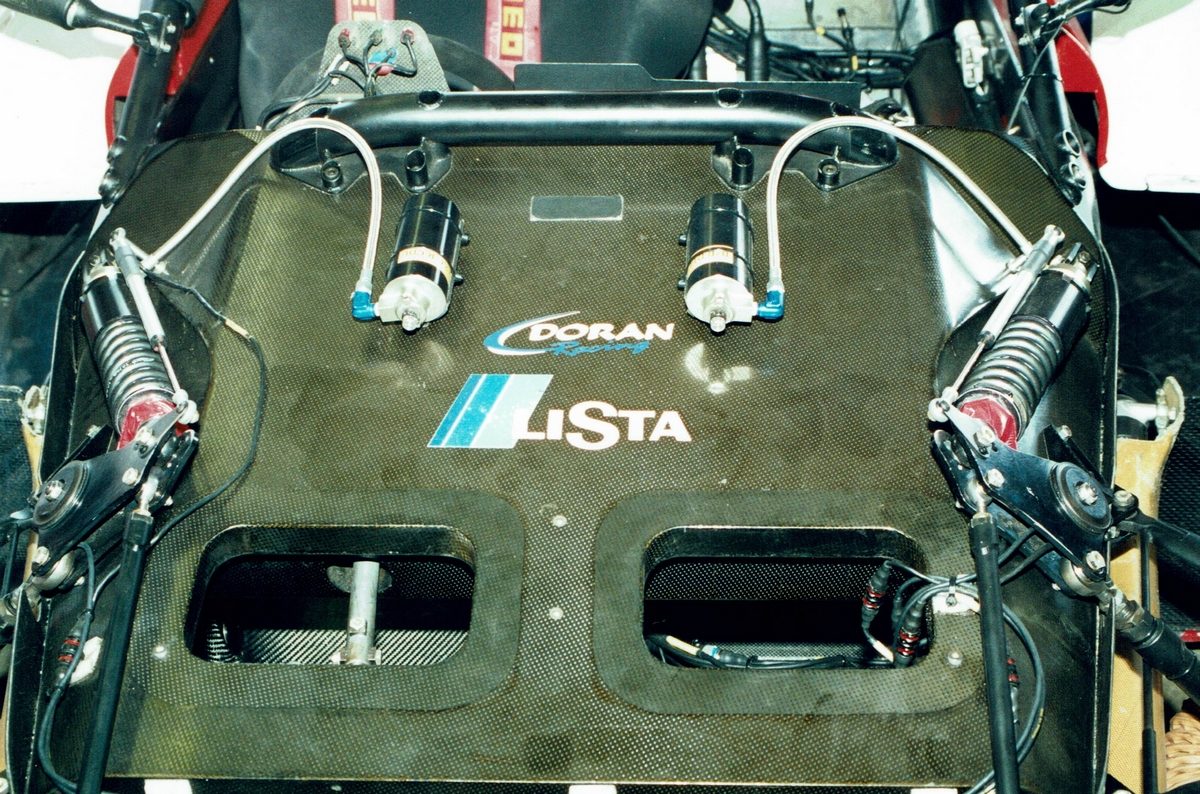

Engine installation in the Ferrari chassis in 2000.

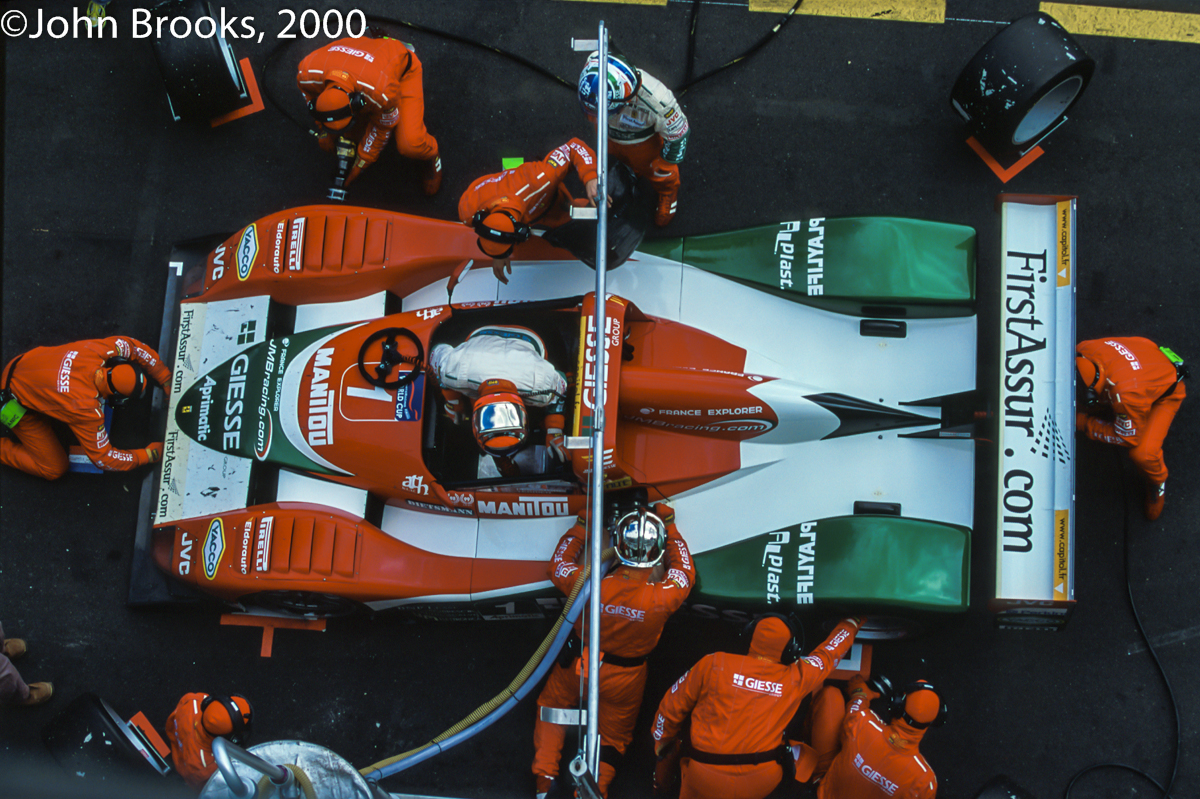

After Daytona 2000, where the Lista Doran team ran the Ferrari V12, Kevin Doran got the idea to put a Judd V10 GV4 in the Ferrari 333 SP chassis. Judd had been doing a lot of development on their engine for the teams using it and it was certainly quick. Getting a 4.0-liter engine to be competitive in the ACO/ FIA regulations required a lot of dyno and electronics work and testing, which Judd had done. This engine was to be installed in chassis #025 which the team had been running since the beginning of 1999.

Judd V10 engine rear view in Ferrari chassis

However, this was not an easy conversion as the V12 engine was longer than the V10 as it had two more cylinders. A bell housing spacer and a few other pieces were needed to make it all fit with the standard Ferrari gearbox and suspension. Hence the “FUDD” (Ferrari- Judd) was born. The Doran team, led by Kevin Doran and Jeff Graves, completed the conversion between Daytona and Sebring in 2000. The team showed up for the 12 Hours of Sebring with chassis #025 now powered by a Judd engine. Renzo Setti, the Ferrari factory engine rep who supported us at the races in the US, came, took one look, and said, “Ok, that’s it, I am on vacation now”. The car at Sebring, driven by Fredy Lienhard, Didier Theys and Mauro Baldi finished an excellent 5th place, the first privateer, behind the two factory Audis and the two factory BMWs but ahead of the surviving factory-run Cadillac. After that great start the team ran the “FUDD” for the rest of the Grand-Am season. The results were good, with victories at Miami and Elkhart Lake, and finishing 2nd four times. At the conclusion of the 2000 season, chassis #025 was sold to Dennis Black and then converted back to a Ferrari V12 engine.

The Judd engine was first installed in chassis #025 which was run by the team in 2000. Here the car sits in the Lime Rock Paddock.

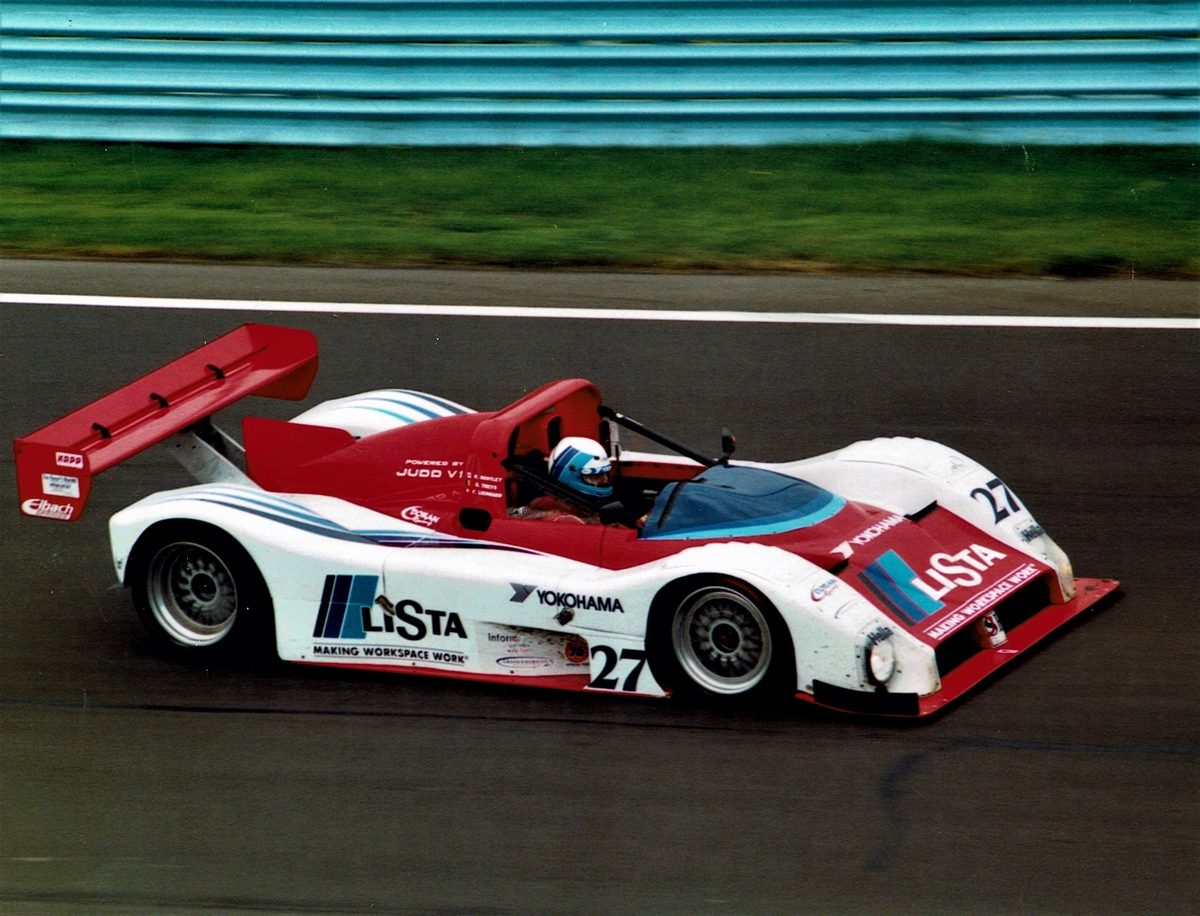

Fredy Lienhard drives the first “FUDD” at Watkins Glen in 2000. This is chassis #025. Note the decal on the engine cover…. powered by Judd V10!

At this time, during 1999 and 2000, the original Chassis #012 from Atlanta in 1995 was sitting in a corner at Kevin Doran’s shops in Ohio. Fredy had retrieved it from Michelotto and wanted it repaired if possible as a show car for his collection in Switzerland. Crawford Composites in North Carolina repaired the tub, and Doran Racing rebuilt the car with all Ferrari components and returned it to Switzerland at the end of 2000 for display in Fredy’s collection.

For the 2001 season, Fredy acquired a Crawford chassis and continued with Judd engines.

In preparation for the 2001 Grand-Am season, Fredy had bought a new Crawford- Judd. However, finding optimal setup and handling proved elusive in the first 3 races of the season.

Chassis #012 in 2001. Note the chassis plate is covered up with black tape…..

So in April of that year, the decision was reached to recall chassis #012 from the “museum”, install a Judd GV4 V10 and continue with a known quantity, being what we had run the year before, a “FUDD”. Judd had continued development of their engine, so the GV4 V10 made good power (about 625hp) and almost as important, improved fuel economy.

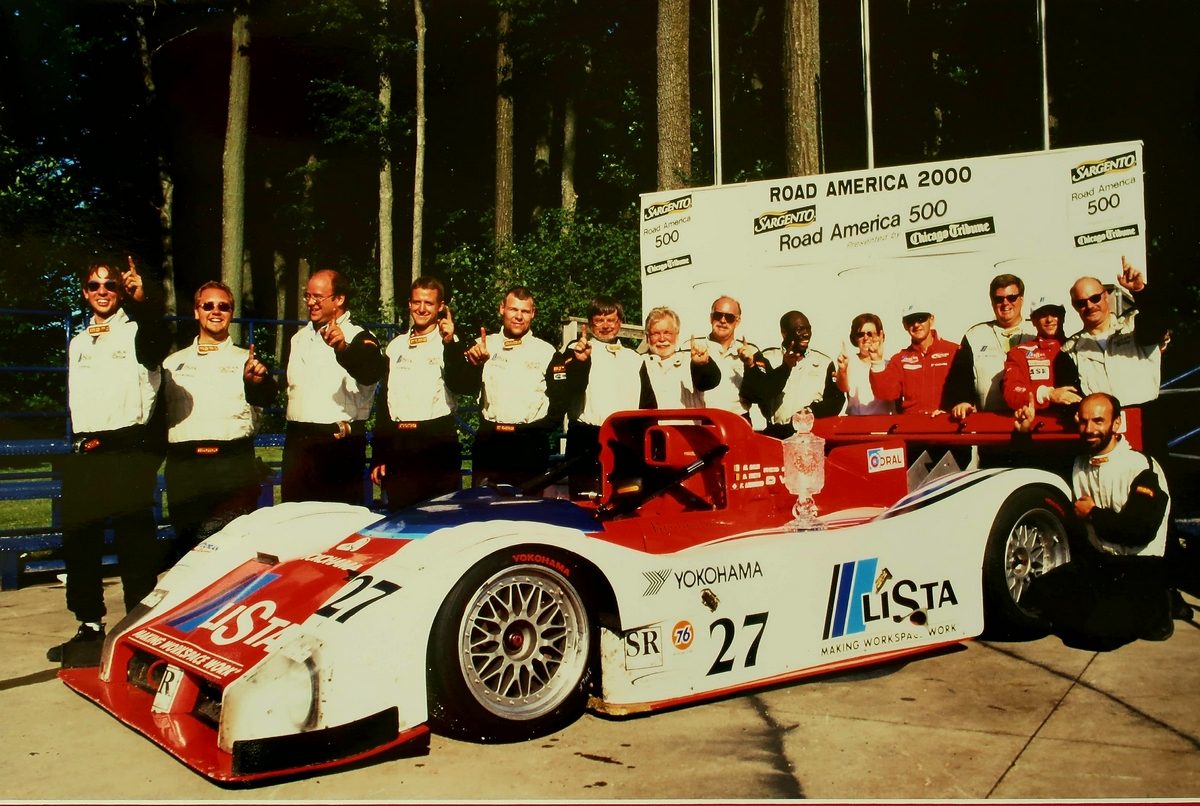

Chassis #012 (the original) was returned from the “museum” and run with Judd engine for the remainder of 2001. Here it has just won the Elkhart Lake race and sits in the victory lane with drivers and crew.

This became readily apparent at the Grand Am Elkhart Lake event in 2001. This was a 500-mile race on a 4.0- mile circuit. Therefore, would be run over the distance of 125 laps. It was a nip and tuck battle over the first part of the race between us, various Riley & Scott cars, and the Risi Ferrari, who were still running the V12 Ferrari engine. At lap 75 we pitted and Fredy Lienhard turned the car over to Mauro Baldi. We knew if Mauro could make it to Lap 100, he would turn the car over to Didier Theys, and that would be the last pit stop. Soon, as the race passed 90 laps, all the other cars pitted, out of fuel, so would have to make another stop before the end. I heard a report later, that in the Grand – Am Race Control Tower, someone said, If Baldi makes it to lap 100, the race is over. He drove superbly and made 101 laps and pitted almost out of fuel. Theys took over and ran to the end and victory while everyone else stopped to top up their tanks once more. The Judd work on the engine had paid off. We had made one pit stop over the last 50 laps (200 miles), while everyone else made two.

Mauro Baldi in #012 at Watkins Glen in 2001, where he, Fredy and Didier would finish 2nd.

We ran the “museum car” for 7 races till the end of the season, winning twice, finishing 2nd once and 3rd four times. At the end of the season, the car was converted back to a V12 Ferrari and returned to the Autobau in Switzerland, where it still resides today. It usually still stretches its legs at track days in Europe, at least once per year.

Fredy Lienhard and ong-time Ferrari engine man, Renzo Setti, at Mugello in 2018

Postscript – Riding in a Ferrari 333 SP

Fredy Lienhard still owns 333 SP #012, it sits on display at the Autobau in Romanshorn Switzerland. From time to time, he takes the car out to “track days” for his friends and business associates. I worked on his race teams for Kevin Doran for many years, so was fortunate to be invited to one of these events in early 2018 (and 2019) at Autodromo Internazionale del Mugello in Italy.

Myself and 333 SP driver, Didier Theys, at Mugello in 2018 after some laps in Chassis 012.

Weather permitting, I would get the opportunity to go for a “ride”, as a second seat has been mounted in the car for passengers. Although I had worked on these cars for many years, changing engines, gearboxes, installing and removing suspension and brakes, I had never actually been driven in one. The only real race cars I had ridden in were a Porsche 935 in the late ’70s, and a BMW 235-i cup car. Having had quite a bit of history with this Ferrari, it was with some anticipation that I looked forward to seeing what it was like to actually sit in it at speed.

The water pump system used to preheat the water prior to starting the engine.

Mugello in March can be cold. In fact, the days we were in house at the circuit, there was snow on the hillsides around the track which sits in a valley. So, it was unclear if this was going to work or not. The 333 SP has to be warmed up with a water heater, especially during cold weather, as there is a danger of the radiators splitting. The minimum recommended water temperature to start the car is 50C.

Keeping the helmet steady while riding aboard the 333 SP

Despite the cold temperatures, we got the car warmed up, and Didier Theys took a few laps to make sure all was in good order. I suited up, and prepared to get in. The immediate sensation is that this is a tight fit. The second seat, if you want to call it that, is just some padding and some belts next to the driver. Getting in and buckling up, the sensation is that you are sitting on the pavement. Very different from a road car or race car based on a road car such as a 935 Porsche. The Ferrari is a 680 HP go kart! Acceleration is massive, the car just leaps forward. The noise of the engine without earplugs is deafening. As you exit the Mugello pits, you are on a long straight, the longest on the course, you go over a rise, then descend slightly downhill to the first corner which is a long radius 180- degree right hand corner. At the end of the straight in this 333 SP, the speed is in the neighborhood of 185 mph. Braking here is very, very impressive in this car and this car has steel not carbon brakes. The first impression of a non-driver is that there is no way the car will stop, however it of course does (Didier later told me he was braking 50 meters early, only running at about 80% capacity). I am convinced the G force under deceleration would throw you out of the car if you were not strapped in tight.

Renzo Setti, John Toohey and myself returning #012 to the Mugello garage after some laps

Due to the “passenger” seat configuration, I found my head was sticking up into the airflow more than Didier. Also, there is a small windscreen in front of the driver about ½ inch tall which helps deflect air which of course is not on the passenger side. The force of the air tended to want to rip my helmet off. So, I had to hang on with one hand and hold the front of the helmet down with the other to see where we were going. All the while, I had to be careful with the spare hand, as right in front of me was the switch panel, with all the ignition and fuel switches. I had to be careful not to hit one of these by mistake!

Mugello’s pit lane

We were on track with other racers. Most of them were GT based such as Porsche GT3 Cup cars and the like. So, we overtook a lot of people in the few laps we did. Passing was kind of disconcerting, as again the 333 SP is so low, I found myself looking up at the door handles of the cars we were passing! A strange sensation for the uninitiated. As we zipped through the traffic, the car just leapt from one corner to the next. While the car looks smooth and composed when you are watching it go by, the ride was a lot more brutal and jerkier when on board. The power allowed the 333 SP to just cover a lot of distance very quickly compared to the other cars. I tried to imagine driving this car at the Daytona 24 hours at night, trying to cope with the slower traffic. A mind- boggling thing to comprehend. As we progressed, I tried to put myself in the driver’s seat. I thought, ok, would I stick my nose in this corner to pass this GT car? Most often the answer was NO! I asked Didier later how he knew these guys would not come over on us in the corner. His response, “My nose tells me, after many years of experience!” But I guess that is why he is the driver and I am the mechanic!

The Cockpit of #012. Passenger seat on the left!

Riding in close proximity to the others, in an open cockpit car you notice quickly the exhaust smell of those in front of you. No doubt this was due to my head sticking up in the airflow higher than the driver. Didier said it did not bother him, as the air goes over the driver’s head due to the shape of the front windscreen.

Brakes on #012 today, steel rather than carbon Brembo, still very impressive brake performance

Too soon, it was over, and we returned to the pits. I was left with the feeling, that every race mechanic should take a few laps as passenger in the cars they are working on. Very quickly, you begin to understand what is at stake here, and how fast you are going, what could potentially go wrong and what the consequences might be.

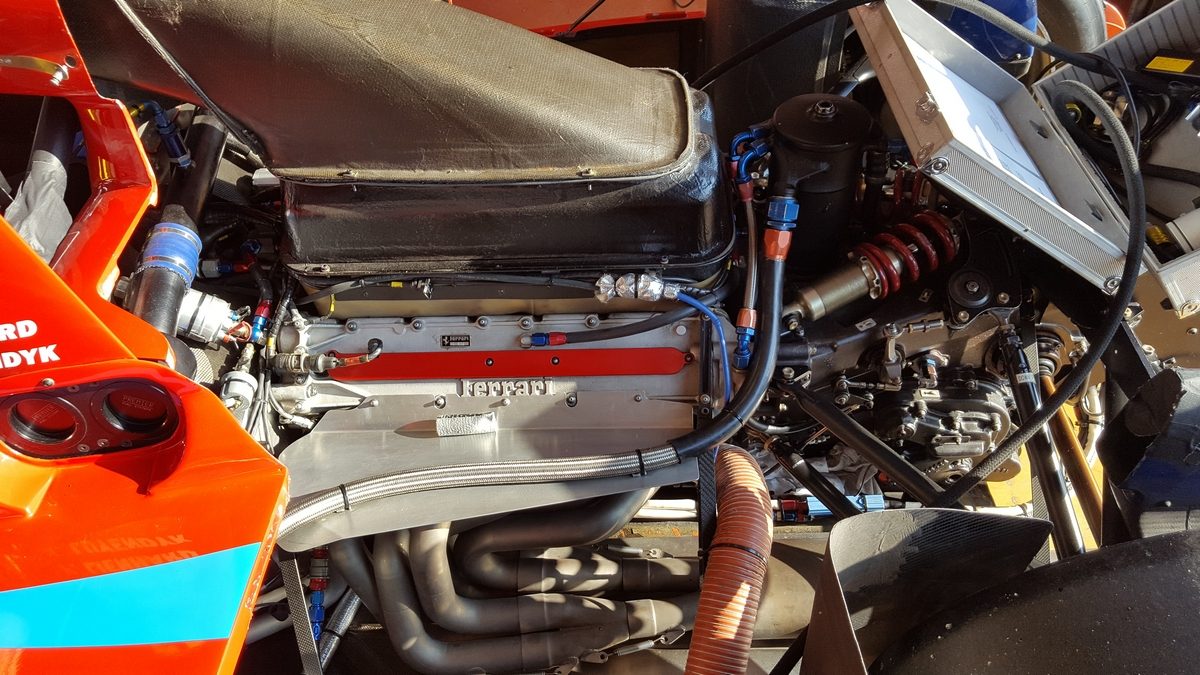

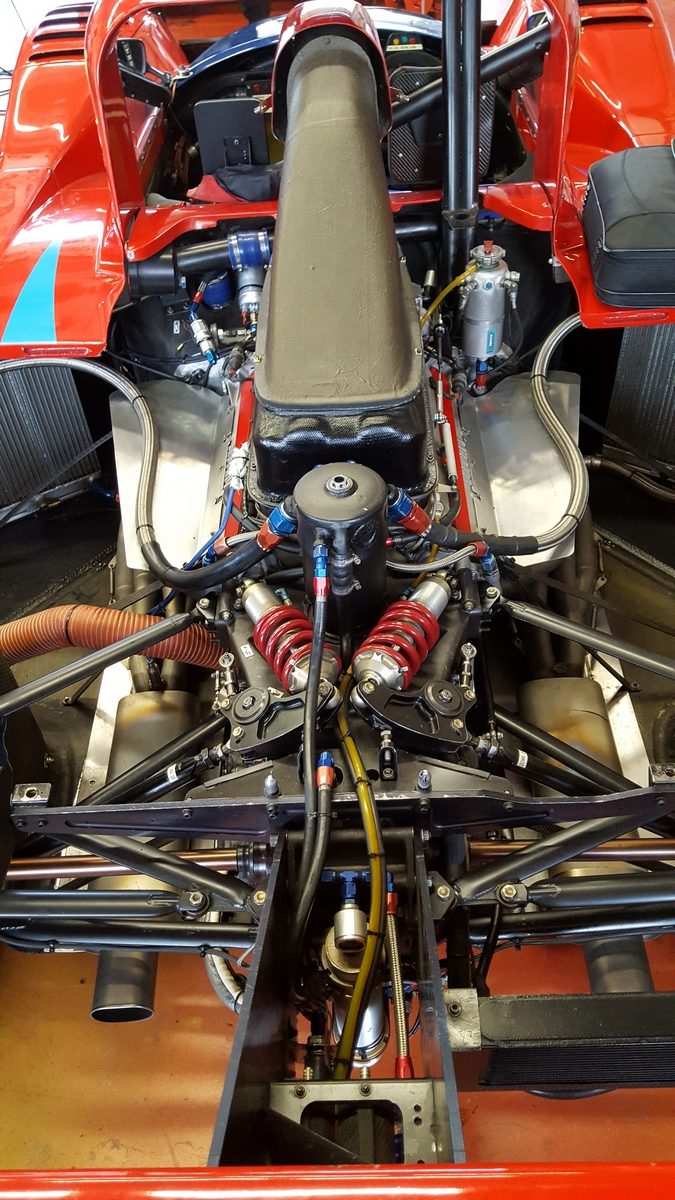

Chassis #012, with the “regular” engine

All in all, an incredible experience to ride in this historic sports racing car, at the famous Italian track which is owned by Scuderia Ferrari. In the USA, we call this a definite “E-ride” (referring to Disney World’s rides ranging from A, the lowest and easiest to E, the most impressive). It was a short glimpse of what is “possible”, and what most of us never encounter. After providing a day to remember for all in attendance, chassis #012 returned to its place on display at the Autobau, where it still sits today.

#012 at Mugello

Fredy Lienhard sits in #012 at Mugello ready for some hot laps.

Ferrari V12 and rear suspension in #012 .

Ferrari enthusiasts one and all! Didier Theys, Paolo Devolder, Martin Raffauf, Fredy Lienhard and Dino Sbrissa. Unfortunately Renzo Setti was ill and did not make the 2019 photo……….

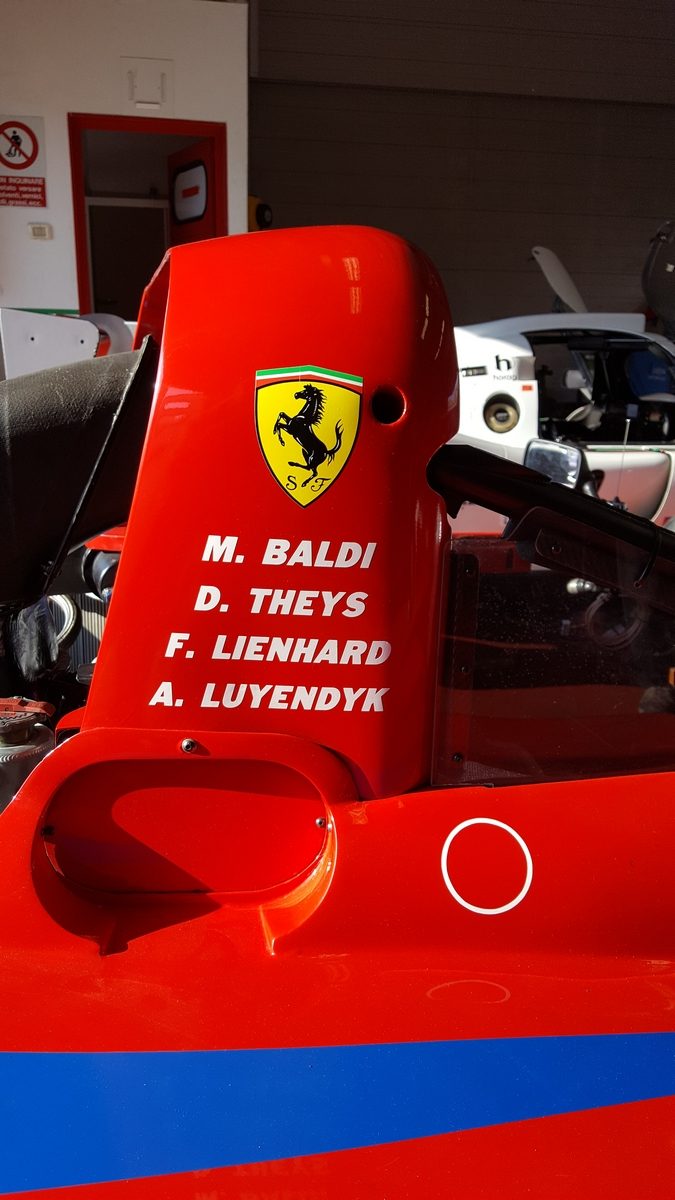

#012 carries some good names……….

Martin Raffauf, May 2019.

Photos copyright and courtesy of Fredy Lienhard, Kevin Doran, Martin Raffauf and Dino Sbrissa