The internet is a wondrous thing, every day some fresh delight is discovered on the screen. A few weeks or so ago, I had this excellent piece in from our old friend Janos Wimpffen, the Sage of Seattle. It describes a true “back our roots” endeavour, the Thunderhill 25. Enjoy…………..

Never Flagging

Welcome to the ultimate “run what you brung” endurance race. Set in the desert hills just above the Sacramento Valley and about 100 miles north and east of the Bay Area, this 2.86-mile rolling 15-turn course has hosted this wacky twice round the clock + 1 hour club event since 2003, and a 12-hour variation before that. It has grown in stature since then, adding a smattering of quasi-works entries and a growing list of pro drivers. However, it has done so without ever compromising a casual feel that is the antithesis of Daytona and Le Mans. Press credentials?—you don’t need no stinking press credentials, show up, sign the release, and wander the paddock. Got a team to enter? Wad up some coat hangers into a roll bar and bring your car, we’ll find a class for it. Well ok, it’s not that casual, but you get the idea.

The race is sanctioned by NASA, not the people who run the Space Station, but rather the National Auto Sport Association, a growing group that has given the rather stuffy SCCA a competitive run with a mix of track days, timed runs, and wheel-to-wheel series across numerous regional divisions. The Thunderhill 25 is the club’s centerpiece event. The track’s California location means that even with an early December date, mild weather can be expected. Such was not the case with the 2013 edition. A lingering cold front hung over the west coast, bringing heavy rain to the more southerly San Joaquin Valley, snow in the surrounding Mendocino hills, and very cold but clear weather in and around the nearby town of Willows. The long December night assured hours run at or below freezing temperatures.

The 60-car entry was divided into six classes. The fastest, ESR, consisted of two Suzuki powered Radicals, a supremely fast Wolf-Ford, a Norma-BMW, a Spec Racer Ford, a Mazda powered special, and two strange homemade tubeframe open cars built around BMW components—sort of a FrankenBMW mated with the old Cannibal of WSC days.

Big Name, Big Hope. The extremely fast but highly fragile sports-racers have rarely survived long at Thunderhill. The addition little Al and even littler Al was not enough for the Wolf as its engine went out while fighting for the lead.

While rising star Ivan Bellarosa was the fast man in the No. 52 Wolf, and ultimately set the pole time, two of his teammates represented one of the most famous families in American motor racing—Al Unser, Jr., and his son, Al III. The Norma had Randy Pobst, Michael Valiante, and Brian Frisselle on the roster while the other Davidson Racing entry, a Ford powered coupe called the DR, had Burt Frisselle and Mark Wilkins, names familiar to most sports car fans.

The DR was actually in the ES class which consisted of a mix of closed top prototypes, proper GTs, and the hottest of the touring car brigade. Burt Frisselle put the No. 16 DR Eagle on the class pole, followed by another American iron V8 car, the Superlite SLC with Michael Skeen leading the charge. Next up was the No. 00 Porsche 997 GT3 Cup entered jointly by Award Motorsports and all-around GT man Pierre Ehret. They were defending champions and were crewed by several people fresh from Flying Lizard Motorsports. Tyler McQuarrie, Memo Gidley, Vic Rice and Lizard crew chief Tommy Sadler were among the drivers.

Early Christmas Present. It was a low key family and friends affair, made festive for the season. The Bay Area based Acura overcame some wheel and suspension issues to finish a fine second in a very competitive class.

ES was a most spectacular mix of cars. Three older Porsches and a pair of BMWs represented the more conventional entries. Lexus USA made a foray into endurance racing with an IS F while an Audi TT RS from German based Rotek Racing was one of several international entries at the 2013 race. Another car from far flung regions was the No. 11 Seat Leon Supercopa of the Aussie-Kiwi consortium, Motorsport Services. They have been regulars at such 24 races as Dubai and Barcelona. SCCA World Challenge entrants GMG brought an Audi R8 LMS to round out the most competitive cars in the ES class. To this must be added an only at Thunderhill entry, the No. 66 Chevrolet Silverado pick-up truck. It is actually a 13-year old tubeframe chassis built for short track ovals and gradually modified to run reasonably well on road courses. Another oddity was an ancient Mazda RX-3, running an early 1980s vintage high-end 12A two-rotor motor. A Panoz Esperante and another V8 powered prototype coupe, the DP look-alike Factory Five, completed the class.

The contents of the remaining classes were a bit closer to normal, although there too the Thunderhill quirkiness could be seen. The starters in the E0 class were all BMW sedans with a Mustang Boss 302 tossed in for good measure. Several Acuras, Lexus, and a Honda S2000 populated E1. Strangest in this group was another car built for ovals, a tubeframe Camaro. The strongest factory presence was also in E1 where three Mazda 6 diesels were in the mix. These were stock production cars unlike the SpeedSource built cars that ran in Grand-Am during 2013. Mazdaspeed billed it as two dealer cars versus a single factory entry. They also had an express target of going the distance on one set of tires. As a result their lap times were as conservative as one could imagine. The drivers tended to only use the top two gears, enabling the diesel’s fine torque to gain momentum.

There were four privateer Mazdas in the E2 class. These include two later generation Miatas and two rotary powered cars, an RX-8 and a RX-7. Another international entry garnered considerable attention. It was the Spoon Racing Honda CR-Z hybrid. The crew came mostly from Japan’s endurance series, Super Taikyu and had veteran Naoki Hattori as the lead driver plus Japanese drifting champion Daijiro Yoshihara learning how not to slide a car. Mazda Miatas are historically the single most popular model at the Thunderhill 25 Hours and all but one of the nine starters in the E3 class was a popular MX-5. The outlier was a Honda Fit.

Thunderhills Indeed. The Fantasy Junction Acura heads downhill on the back portion of the course. Despite some cloudy periods, there was no natural thunder in the cold, dry hills.

The weekend schedule had open testing on Thursday and a long free practice session on Friday. During these periods there were any number of extra cars circulating. Most of the Miata teams had spare cars while cars from the western regional Radical series were employed to give extra seat time to their team drivers.

A single 30-minute qualifying period the night before the race decided the grid. It took place into sunset so that relatively few teams took it seriously for speed as they were mostly intent on night time settings. A good set of headlights are supremely important at Thunderhill as when the sun goes down the desert is well and truly dark—and very, very cold.

Bellarosa’s time in the Wolf of 1:37.662 was not only the fastest overall, but nearly 5 seconds clear of all rivals. Burt Frisselle in the Davidson Racing DR also had nearly the same gap on his ES class rivals, the Superlite being second fastest. The fastest “production” car was in tenth overall, the No. 86 tubeframe Camaro driven by California oval track man, Mike David. The Fantasy Junction racing Acura of Spencer Trenery was nearly nine seconds back, second in the E1 class. The remaining three classes had much narrower gaps between first and second. The Pure Performance BMW of Brett Strom edged a similar M3, while the newest of the rotaries, the Team RDR Mazda RX-8 of Dennis Holloway edged the No. 7 BMW in E2. Somewhat predictably, the closest contest was in the near-spec E3 class where the No. 05 Miata of Sonny Watanasirisuk was less than a second ahead of the identical No. 35 Spare Parts Racing Mazda.

One pre-race favorite that missed qualifying was the No. 08 Audi R8 LMS. Drew Regitz backed into a wall early during practice. The damage at first seemed severe but a long thrash revealed that only some suspension components and bodywork needed replacing on the left rear. Alex Welch was able to make the start from the back of the grid.

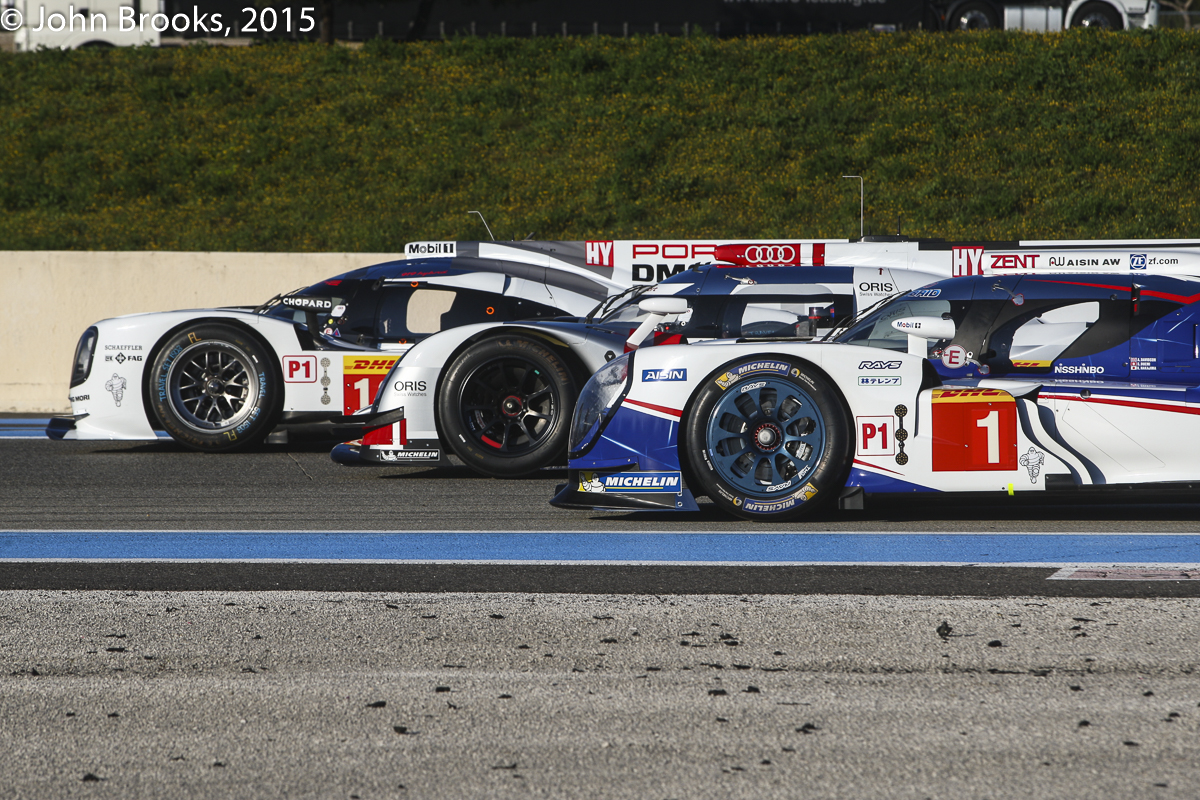

More or Less Equals. Three V8-powered prototypes lead a trio of Porsches, representing the top of the grid at the start. Behind them is the eventual class winning Radical and the overall winning Audi.

A relatively balmy 41 degrees F greeted the starting field. The 11:00 o’clock starting procedure is a bit unusual in that in consists of one pace lap that returns via pit lane, then another standard formation lap, and finally the green flag. Even before the start there was trouble with the Norma. Brian Frisselle brought it in with an oil leak. Several more stops ensued before the engine expired. Another quick runner, Mike David in the Camaro, also became a chronic early pit caller. Their clutch linkage problems would be solved after some delays.

It has become somewhat axiomatic at Thunderhill that the prototypes will run clear of the production cars in the early going but then fade and retire before yielding to production type cars. At least one of these predictions nearly came true in the opening lap when Ivan Bellarosa spun at Turn 1 of Lap 1—a near repeat of a year earlier.

Extreme Endurance Spirit. The PTG (yes, that PTG) entered Factory Five quasi-DP looking prototype caught fire on the four lap of the race. Any sane team would have gone home and warmed up. But at Thunderhill sanity parks at the gate and the team spent over 20 hours rebuilding the car, finishing the race just a tad behind the leaders.

The Wolf recovered at the tail of the field while Mike Skeen slipped by into the lead with the Superlite. However, he either couldn’t or didn’t hold off a charge by Burt Frisselle and on lap 4 the No. 16 DR took the lead. Less than 8 minutes in came the first full-course caution. Another prototype, the No. 4 Factory Five of Davy Jones started an internal barbecue in the engine compartment at Turn 10. Incredibly, the team attempted to rebuild the car, awaiting a new engine to be shipped in from Stockton while rewiring most of the rear portion of the car. They returned to the race at 10:30 on Sunday, meaning that their third lap clocked in at about 22-1/2 hours—a true zombie effort.

Almost simultaneous to the fire, Ryan O’Connor ground to a halt with the Retro Racing RX-3. It was towed in for the first of two engine changes to its little rotary—tows and motor changes are allowed in NASA space. By the way, their team is retro in more ways than one. The team’s strategy guru is Jerry Hull, who in the early 80s was the crew chief for IMSA GTU champion Dave Kent’s Racing Beat Mazda team.

Two cars effectively started the race 30 minutes late, the throttle challenged No. 86 Camaro and the No. 44 BMW E46 of V. j. Mirzayan which was unable to fire up on the grid. The team was clueless as to why, but suddenly it started running like nothing happened, until later it died as if it never ran—the mysteries of auto electronics. Cooling system problems would eventually kill the car—ironic given the frigid weather.

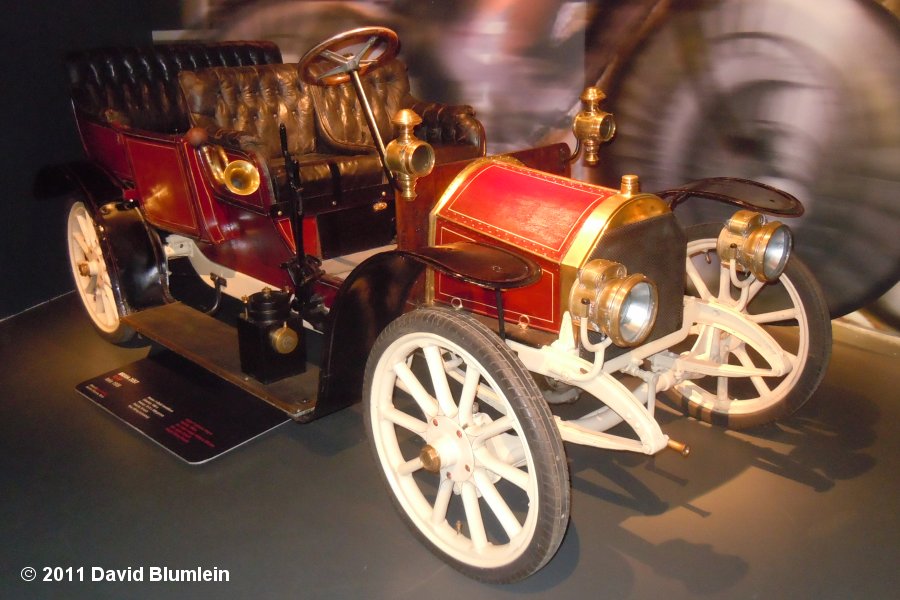

Winter becomes Eclectic. These were just two of the weirder entrires. The open top pseudo BMW was one of two similar homebuilt cars—completed only a week or so before the race. The Silverado pickup led for many hours in 2012. Neither car finished.

Two cars were genuine non-starters, both with engine maladies. The No. 19 Lang Racing BMW M3 team went home while several of the drivers from the No. 21 N1 Racing Lexus IS300 switched to the team’s No. 79 IS250

Malcolm Niall pitted the Down Under Seat early on. The team would henceforth have a mostly backsliding race of good charges interspersed with long stops. It was a somewhat better saga for Alex Welch in the Audi R8. It was generally forward progress from the back of the field, with several minor delays along the way. The most remarkable recovery was by the Wolf, up to second overall by the 40 minute mark.

Bellarosa remained on a tear and took back the lead on Lap 19 after turning in a fast round of 1:39.660. He remained in first through to the end of his scheduled stint, handing over to team owner Miles Jackson. This handed the lead back to the Superlite, which was driven in succession by Darrell Anderson, Tim R. Bell, and Chris Durbin.

The Frostbite 25. Keeping warm was the main priority all weekend. The Facotry 48 Radical strikes a pose during practice. It finished second in the sports-racing class, with only three of seven starters making it to the flag.

Another prototype, the No. 48 Radical began a series of unscheduled stops, compounded with the first of several penalty box visits for passing under the yellow. NASA rules are quite strict about transgressions with each subsequent violation incurring ever longer sentences. It became routine by about the 4-5 hour mark to see cars held for as long as 10 minutes at the end of pit lane.

The No. 22 may have been an ersatz BMW, but it suffered from a problem very typically associated with the rear-wheel drive marque, a broken differential. It would later stop with the same problem during the night hours. A more standard BMW, the No. 33 Bavarian Tuning Motorsport M3 of Billy Maher had terminal misfire problems, completing only a handful of laps across several hours. There was much discouragement within the Fresch Motorsport team (No. 32 BMW 325is). One driver was a no-show and they were unable to close negotiations with two other drivers to join them. With only Thomas Lepper and Jarrett Freeman, Jr. left on the roster, they completed a few stints and then packed up.

ALMS Memory Lane. Here’s a tribute to Don Panoz. Thanks for bringing us 15 years of some of America’s finest sports car racing. Like this Esperanate, it was not always perfect, but it was fun.

The Panoz became another paddock dweller, replacing the clutch slave cylinder. They also fell afoul of the circuit’s strict noise limitation (a frequent issue for several V8 powered cars).

The No. 16 DR began a long series of woes, including a broken exhaust, a split c.v. joint, and a collapse of the rear wing assembly. It then began to regularly toss alternator belts. Well into the night the Davidson Racing team finally threw in the towel, with both of their entries (the Norma was the other) meeting their maker.

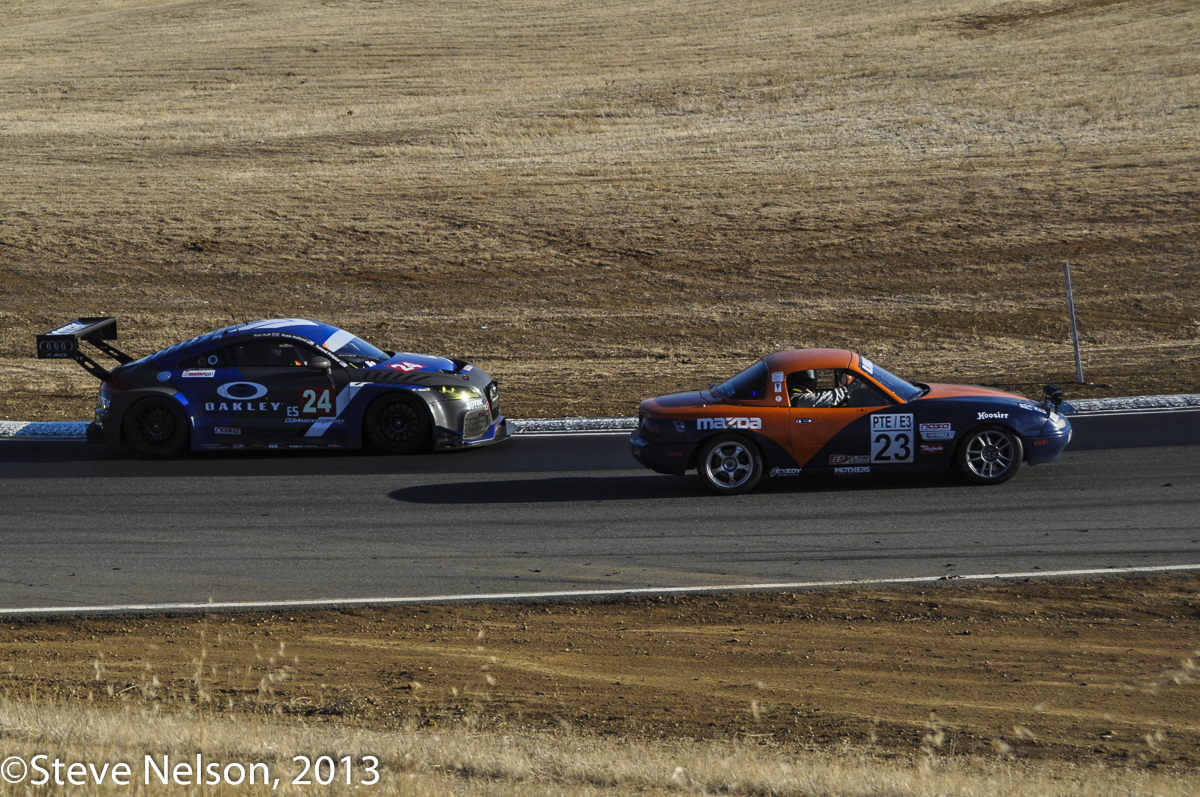

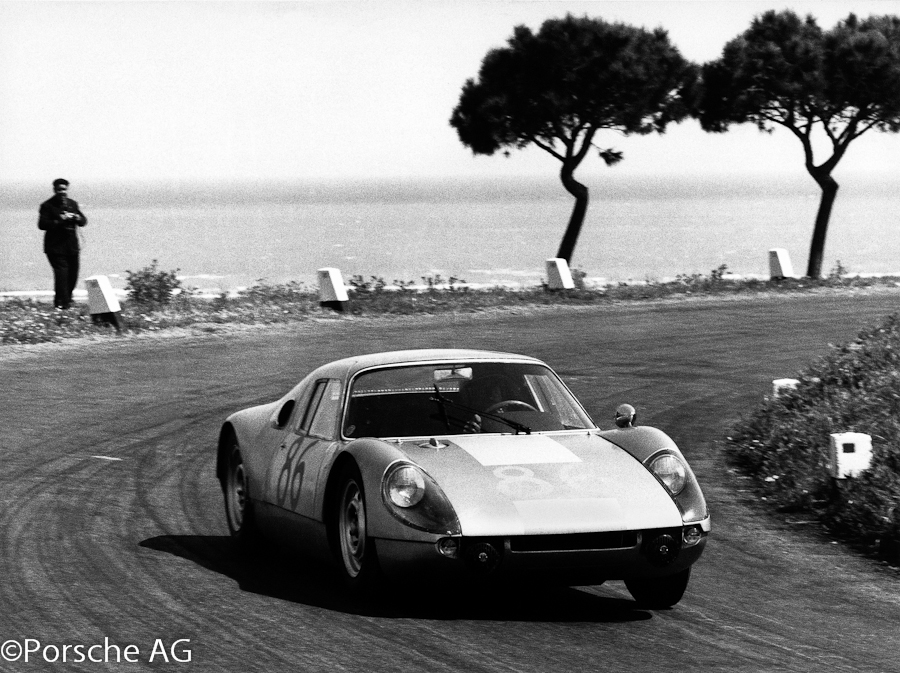

Old Time GT Racing. A tube frame Camaro is dicing with the Flying Lizard run Porsche. No. 86 was a short-track racer converted to road courses and was fast in between long bouts of endless problems. The Pierre Ehret driven Porsche was the 2012 winner and led again for several hours before retiring at half-distance with a broken gearbox.

The No. 68 Mazda Miata had but two listed drivers, Bill Brown and Tony Heyer. They are Thunderhill 25 perennials and epitomize the wackiness of the race. The team’s “strategy” is to race till sunset, and then head into town for a leisurely steak dinner. Then after a nightcap it was time to curl up at the motel. Refreshed following a shower, the ultra-civilized duo saunter back to the track in the hills an hour or so before sunrise and finish the race. Brown noted, “We usually finish mid-pack without really trying.” This year was a bit different. The wheel hub broke out on the course and the team realized that repairs may require them to miss their dinner reservations. They knew their priorities, a convivial supper and slumber took precedence over continuing in the race.

Three short safety car periods came in succession before 15:00, six hours elapsed time. Each was for retrieving various stranded cars. Al Unser, Jr. took over the leading Wolf just before 15:00 and immediately following the last of these neutralizations set the race’s fast lap at 1:37.789. The legend hadn’t lost his touch.

One Less. The Mazda Miata MX-5 is the single most popular production based racer in the world and they made up a good percentage of the entry at Thunderhill. Slow but reliable—well, ok, not this one.

The friendly intra-Mazdaspeed contest swung in favor of the two dealer cars when the No. 70 factory entry had to be towed back with left front damage after the crew failed to properly torque the wheel—self-inflicted wound there. The team lost a half-hour making repairs. Others with delays were the No. 03 Superlite (short-ish pit penalty) and the No. 74 BMW which stopped on course with electrical issues. Almost unnoticed, the No. 24 Audi TT began a slow climb past other production cars and the various troubled prototypes. The No. 9 factory Lexus also climbed through the standings, but a little less steadily with several unscheduled stops, including a puncture and a slow return to the pits. The Seat’s climb was interrupted by some continuing electrical issues.

The Wolf came in for what seemed to be a routine stop just before the late autumn sun began to dip. In the desert, when the sun drops it is like turning off a light switch. Darkness comes rapidly. This was a problem for the Wolf as their headlights, bright at first, dimmed as rapidly as the sky. Its electrics were clearly not recharging and the team had to make several visits back to the garage area to make repairs. This passed the lead back to the No. 03 Superlite.

The E1 class turned towards the various Acuras in the field although the No. 5 Fantasy Junction RSX-S did not share in this joy as they were replacing part of the clutch assembly.

Frankenbimmer. For those tired of look-alike GT3 race grids, come to Thunderhill. Only here will you see weird things such as BMW based car built over the Thanksgiving day weekend. Yes, the homely Acura ran better.

A main contender for overall honors, the No. 00 Porsche, had a setback when Anthony Lazzaro backed into a tire wall and the team lost about 20 minutes doing bodywork. Having bog stock production cars in the field results in some rather mundane maladies. Such was the case with the No. 62 E0 class BMW 330 of Melhill Racing. They had a leaky dipstick tube. An important E1 class runner, the No. 79 Lexus, lost time with weak front brakes. One of the lesser Porsches, the No. 29 TruSpeed entry (another ALMS based team) had a broken stub axle.

The first safety car interruption in over four hours occurred at 19:20. It was a rather serious matter when Dan Riley’s No. 20 RX-7 was clipped by another car, spun, and was then t-boned. Riley reported some neck pain and the turn marshals took extra care removing him from the heavily damaged Mazda. During this long 50-minute interruption there was a light moment in the garages. The No. 07 Mazda Miata had a broken clutch pedal and a neighboring crew offered a spare from one of the seemingly dozens of spare Miatas scattered in the paddock. The team finished installing it just as the owner of the donor car arrived on the scene, screaming that he hadn’t permitted the loan and wanted it back on the spot. A mechanic for No. 07 happened to be face down / feet up under the dash making the switch. He wrestled the borrowed part back out and brandished it back to the owner with comments appropriate to the momentary absence of sportsmanship in the otherwise friendly club race.

Another short full-course caution at 21:04 was needed to retrieve the No. 48 Radical which had a small engine fire. It was towed back in and after a rapid 30 minute garage call a new Hayabusa-Suzuki was installed. Three more short neutralizations took place before midnight, all for minor stalls and course blockages. At the top the Superlite continued unabated. They built up a three-lap lead which was frozen in place for most of the night hours. This was an apt metaphor, given that temperatures had fallen well below freezing (18 F and windy, brrr).

Early Race Traffic

Positions remained steady state for several hours, which is endurance racing journalist speak for saying that finding a warm spot to take a nap was in order. The most important retirement during this period was the No. 00 Porsche—broken gearbox. They had earlier made repairs to it, but later problems proved terminal. The No. 52 Wolf had a very good run, recovering to second overall. The No. 24 Audi TT RS climbed to third thanks to a continued mostly untroubled run, only a few self-inflicted penalties costing them time. The No. 08 Audi R8 LMS also rose, hovering around fourth before again making a lengthy stop. There were four notably consistent runs; the No. 83 Barrett Racing Porsche, the heretofore unheralded No. 38 Radical, the No. 27 Honda Research West Acura, and the No. 18 Mustang. All made it into the top ten by dint of thus far untroubled runs. The No. 9 Lexus also returned to this fold after earlier problems with a c.v. boot. But the most remarkable of all was the No. 05 Mazda Miata. The 949 Racing team not only led the E3 class but was in exalted 10th overall at 04:00. The Silverado pick-up had led this race in 2012 but their 2013 race was far more troubled. They spent much of the night period replacing the gearbox.

Blue Lite Special. The Superlite thoroughly dominated the first half of the race. Too bad for them that it wasn’t 12 hours in length.

There were two significant pre-dawn neutralizations. The first, at 04:05—10th full-course caution of the race, occurred when the Wolf was hit and then had a brake failure. Even more importantly, at 05:10 the Superlite came to stop with a catastrophic steering failure. Chris Durbin struggled to bring the car back to the pits but had to pull off course. Suddenly, the car which had been leading overall since sunset was forced to retire.

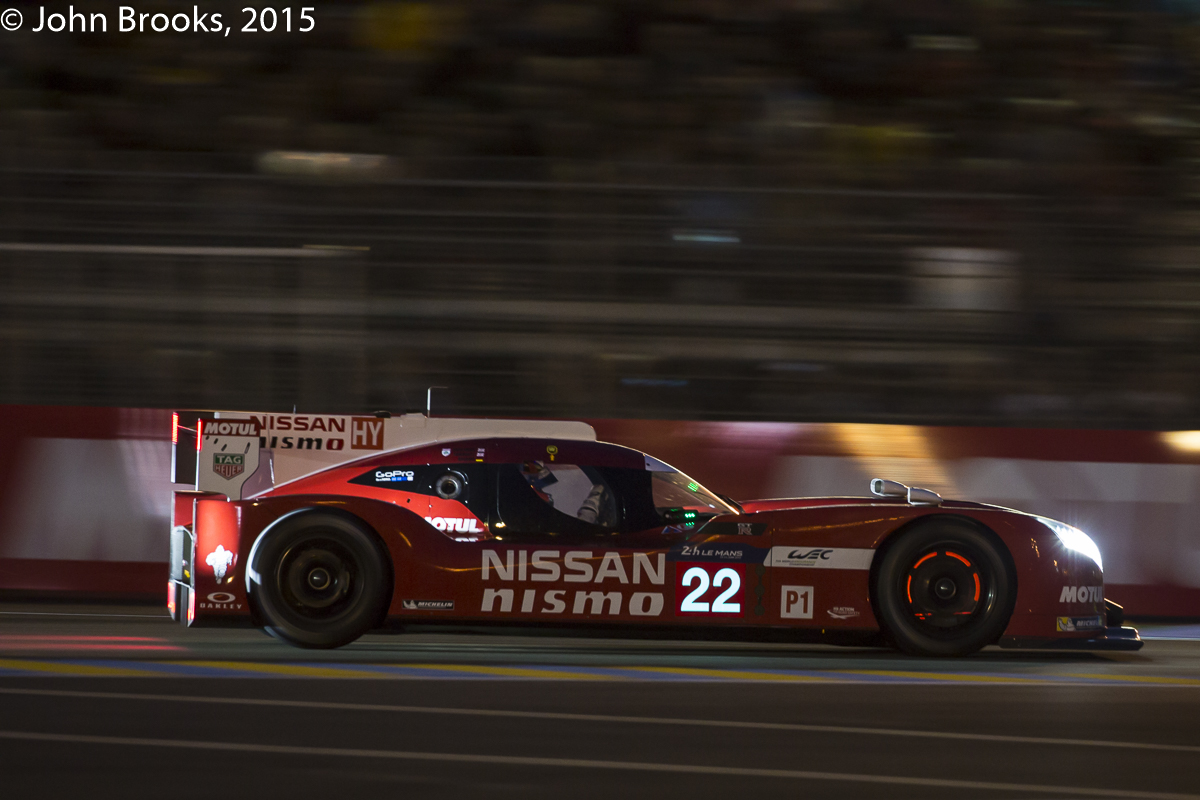

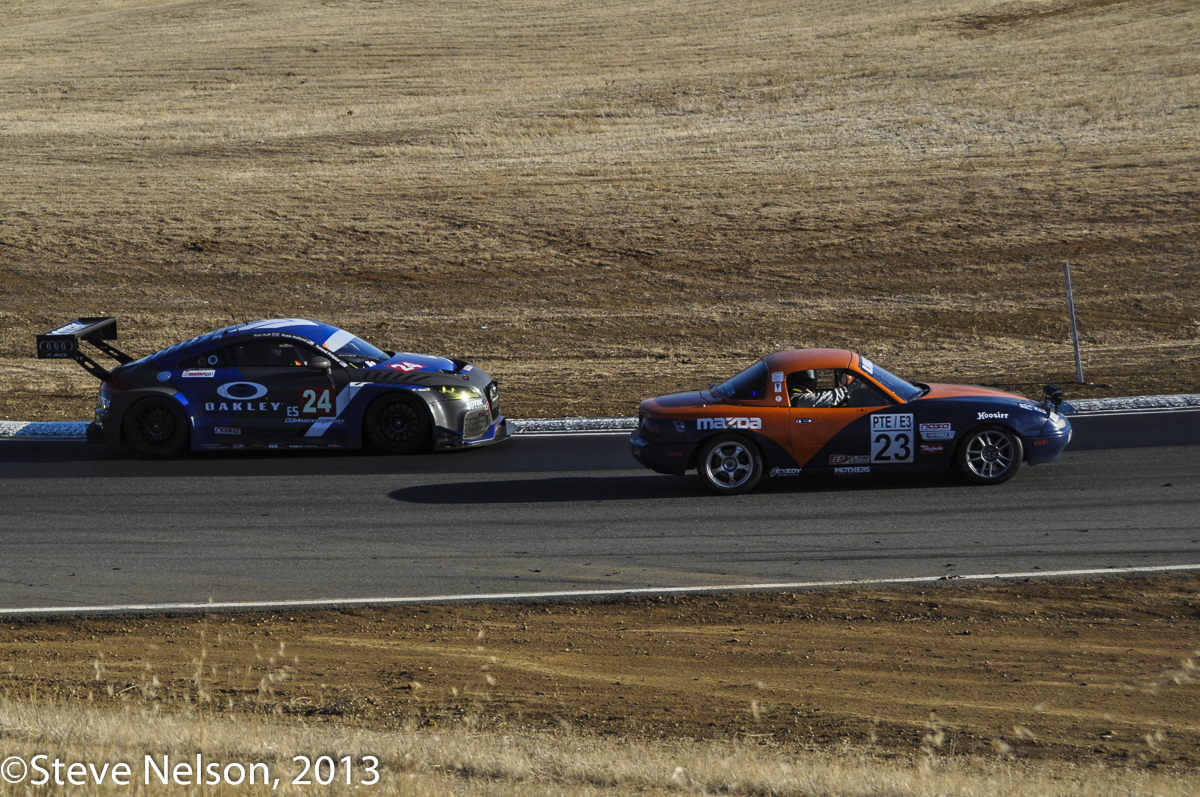

Yin and Yang. The Rotek Audi TT emerged in front when the prototypes wilted, and then never looked back. Late in the race it is putting one of 77 extra laps on the RJ Racing Miata—winner of the nearly all-Miata E3 class.

In proper Thunderhill style, we now had a production car in the lead. It was almost as if the Rotek Racing Audi refused to move into first as it incurred yet another penalty and soon after inheriting the top spot it spun briefly before recovering. The American-British-German driving contingent was now poised to add another gem to Audi’s growing endurance racing crown. Rob Huff had started the race, followed in turn by Kevin Gleason, Jeff Altenberg, Roland Pritzker, and Rob Holland, with Christian Miller holding back as reserve driver.

The Wolf was again in recovery mode and was by far the fastest car on track, albeit 14 laps down. However, at 06:25, its Ford engine exploded after being hit at Turn 1 and this time it was not a case of crying wolf for the No. 52 team. It was well and truly gone.

With the first glimmers of light in the east, this was the situation in the top 10:

1st overall, 1st ES, #24, Rotek Racing, Audi TT RS

2nd overall, 2nd ES, #83, Barrett Racing, Porsche, a massive 23 laps down

3rd overall, 1st ESR, #38, Radical West Racing, Radical, -6 laps

4th overall, 3rd ES, #08, GMG Racing, Audi R8 LMS, -5 laps

5th overall, 4th ES, #9, Lexus USA, Lexus IS F, -11 laps

6th overall, 1st E0, #18, Don’t Crash Racing, Ford Mustang Boss 302, -2 laps

7th overall, 1st E1, #27, Honda Research West, Acura ILX, -1 lap

8th overall, 1st E3, #05, 949 Racing, Mazda Miata, -3 laps

9th overall, 2nd E1, #5, Fantasy Junction, Acura RSX-S, -4 laps

10th overall, 2nd ESR, #48, Factory 48, GTM, -1 lap

The top E2 class car was the No. 78 Sector Purple Racing Miata in 15th overall. To complete the then current podium standings in the various classes, the third place ESR car was down in 30th overall, the No. 49 CSR Performance Spec Racer Ford—another car lately making longish stops. The second place car in E0 was in 13th overall, the No. 62 Melhill Racing BMW 330. There was a close fight for third in class between the No. 31 El Diablo Motorsport BMW M3 and the No. 67 Pure Performance BMW E46, the two circulating in 18th and 19th overall, respectively. The third place car in E1was in 12th overall, the best of the Mazdaspeed diesels, the No. 55 dealer car. The last two podium spots in E2 were occupied by the No. 74 AAF Racing BMW 325i in 21st overall and five spots further back was the No. 34 Mazda RX-8 of Team RDR.

The No. 31 El Diablo Motorsports BMW M3 was the leader in E0 for about the first half of the race and set the fast lap in the class. They were overhauled by the Mustang during the night and slipped to fourth behind the No. 62 Melhill Racing BMW 330 and the No. 67 Puer Performance BMW E46. These two BMWs swapped 3rd and 4th, and later 2nd and 3rd in class several times.

Late Entries. No, the tow trucks are not competitors. Then again, at Thunderhill you never know.

The Fantasy Junction Acura led the E1 class in the opening hours. The top spot was briefly taken by the No. 56 Mazda 6 diesel, before the No. 27 Honda Research West Acura ILX took over and headed the class into the morning. The No. 5 Fantasy Junction team recovered to second in class, ahead of the two dealer Mazdas, with the No. 25 Honda Research West Acura sometimes splitting the diesels.

The leader in E2 for the first half of the race was the No. 34 Team RDR Mazda RX-8. The No. 78 Sector PurpleMiata was second for most of that time before taking the helm of the class during the 13th hour. The No. 74 AAF Racing BMW 325i swapped second in class several times with the two Mazdas. The Japanese Honda hybrid has been unable to rise above fourth in class.

There had been three leaders in the E3 class, all Miatas as the lone Honda has not been fit to make it into the top five. The No. 35 Spare Parts Racing entry started by Hernan Palermo was the first on top, later passed by the No. 07 Pacific Throttle House Mazda. The No. 05 949 Racing MX-5 had been consistently the fastest and did not relinquish the lead after the fifth hour. The No. 23 RJ Racing Miata had a clumsy start but rose to second in class within a few hours.

Coming and Going. While the nearly 3-mile circuit expands over several sets of hills there are also several locations where different sections are in close view. Links allow for various shorter course configurations. The Mazda was one of two Mazdaspeed run cars staffed by drivers representing their national dealer network. If finished second among the three stock 6 diesels.

Sunrise brought little warmth as a north wind kicked in along with the orange disc in the east. At least the dreaded fog was absent. Times did begin to tumble a bit with the improved visibility. The No. 69 Race Epic Porsche was at last running cleanly after having been rebuilt following numerous shunts. The No. 05 Mazda had a long stop but was able to retain its lead in E3 as well as its good overall placing.

It now came time for some of the overall spots to swap around, thanks to inherently faster cars running well and moving forward from lower spots. For example, the No. 48 Factory Five GTM slipped ahead of the No. 27 Acura.

Heading into the final three hours some 35 cars were still circulating, all relatively healthy although of course many were delayed. The latest to hit problems was the No. 07 Mazda which spun luridly at Turn 1 and required a tow (but not a general caution) to pull it out. There was some important drama earlier when the No. 83 Barrett Racing Porsche stopped on track for a brief period. They did not lose second place overall but the gap to the third place Audi R8 LMS narrowed considerably. Then at almost exactly 09:00 it became an Audi 1-2 when the much faster GMG entry passed the 997 GT3 Cup. This culminated an excellent comeback by the No. 08 entry.

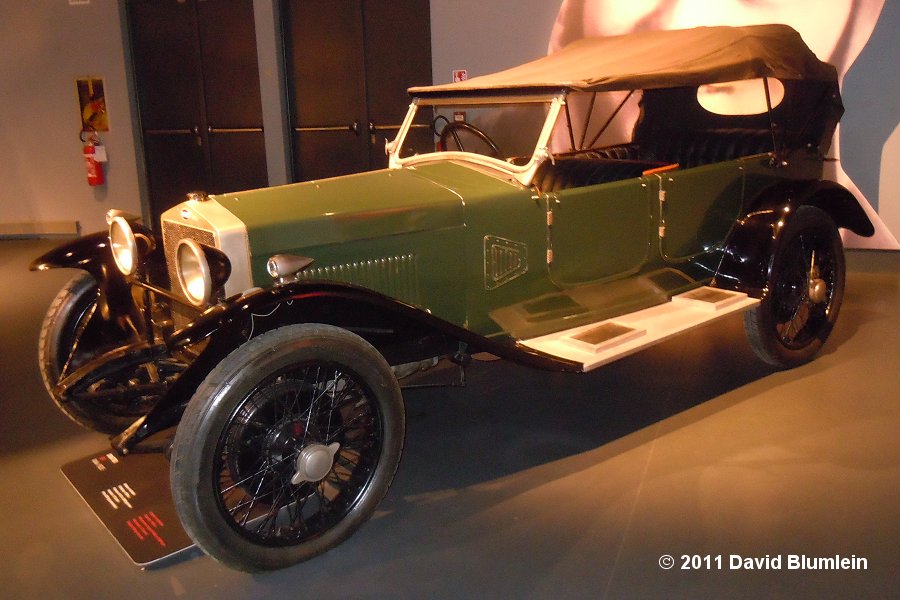

Important Presence. The number 9 Lexus IS F was one of several factory backed entries at this year’s race, signalling the event’s growing importance. They finished fourth in class, a few spots ahead of the Porsche it is trailing at the moment.

With only a bit more than two hours to go there was a change in the E3 class lead. Sadly the long-time great run of the No. 05 949 Racing Miata was stalled and this allowed the No. 23 Mazda of RJ Racing to move to the top. That gap widened to four laps. This left the E2 class battle as the last competitive contest. At 10:00 there was only one lap separating the leaders, No. 78 Sector Purple Racing Mazda from the No. 74 AAF BMW.

The Barrett Porsche again picked up the pace and GMG Audi made another long stop, allowing second place overall to flip again. The top three cars were all in the ES class with the top ESR in 4th. In terms of drivers, here are the class leaders going into the final hour:

ESR, #38, Radical West Racing, Radical: Ryan Carpenter / Todd Slusher / Anthony Bullock / Scott Atchison / Randy Carpenter

E0, #18, Luxury: Don’t Crash Racing, Ford Mustang: Thomas Martin II / Thomas Martin III / Brian Zander / Tom A. Brown

E1, #27, Honda Research West, Acura ILX: Sage Marie / Lee Niffenegger / Matthew Staal / Scott Nicol / Michael Tsay

E3, #23, RJ Racing, Mazda Miata: Rob Gibson / John Gibson / Roger Eagleton / Gary Browne / Jamie Florence

E2, #78, Sector Purple Racing, Mazda Miata: Kyle Watkins / Robert W. Ames / Daniel Williams / Glen Conser

Good Bet Gone Bad. The GMG R8 had all the ingredients of being a favorite; a professional team, a a model and global brand associated with numerous victories, a good driver line-up, and uneven competition. Things began to go awry soon after practiced started. After a huge shunt the crew worked hard to make the grid a day later. It had a roller-coaster of a race, charging to the front before a litany of problems laid it low—ending with the gearbox expiring within sight of the flag and a likely third place finish.

There were last minute dramas when the engine started smoking on the No. 62 Melhill / TFB Racing BMW. Its third in the E0 class was not in threat because of the large gap to fourth, but it did bring about one last full-course caution, the 13th of the race. Sector Purple stretched their lead over 949 Racing and thus solidified the E3 victory. As if they needed more cushion, the overall leading Audi stretched the gap to over 30 laps at the finish. There was enough green running at the end for the ESR class winning Radical to creep into third overall, ahead of the Audi R8. Indeed the GMG entry’s gearbox failed with minutes to go and it was pushed across the line.

Detritus. It’s a classic endurance racing scene. The winner charges through a battlefield of debris. Seen across the Sacramento River valley are the distant foothills of the Sierra Nevada range.

The victory was another feather in Audi’s cap, even if it came from a private team in a TT RS. For Thunderhill and NASA it was another step towards creating an ever higher profile event.

A Podium?

(The amended results show that the second place 949 Racing Mazda Miata in E3 has been disqualified for mounting improper parts. Of course, in this class the Mazda 1-2-3 is still retained)

Janos Wimpffen, January 2014