Pedro

There comes a point in all our lives when we reach a crossroads, the road we take determines our future, rarely do we have the chance to go back. Often we are not even aware that the choice has been made or is really significant. For me this position was reached some 40 years ago and certainly at the time I was oblivious to the consequences. However if I had not taken that course back then, it is highly unlikely that I would be writing for you, the audience, today.

Siren Song

1971 was the year when I really caught the motorsport virus, from that small start I have ended up making some sort of career out of the sport, but it is at that time that I passed the point of no return. I had been following the glamorous and seductive racing scene second hand, reading everything and anything I could about this world, so unlike my own life as a rather dull-witted schoolboy. Some of my contemporaries found their escape in Hollywood, I found it at Le Mans, at Monaco, at Nürburgring, anywhere that racing happened. Autocar, Motor Sport, Autosport and other long forgotten titles were devoured eagerly, I can still remember race results from 1969, when now I get confused about what happened ten minutes ago. I had actually managed to attend the 1970 British Grand Prix, seeing Jochen Rindt score a last lap victory over Jack Brabham but the following year I was geared up for seeing as many races as I could.

Heroes………

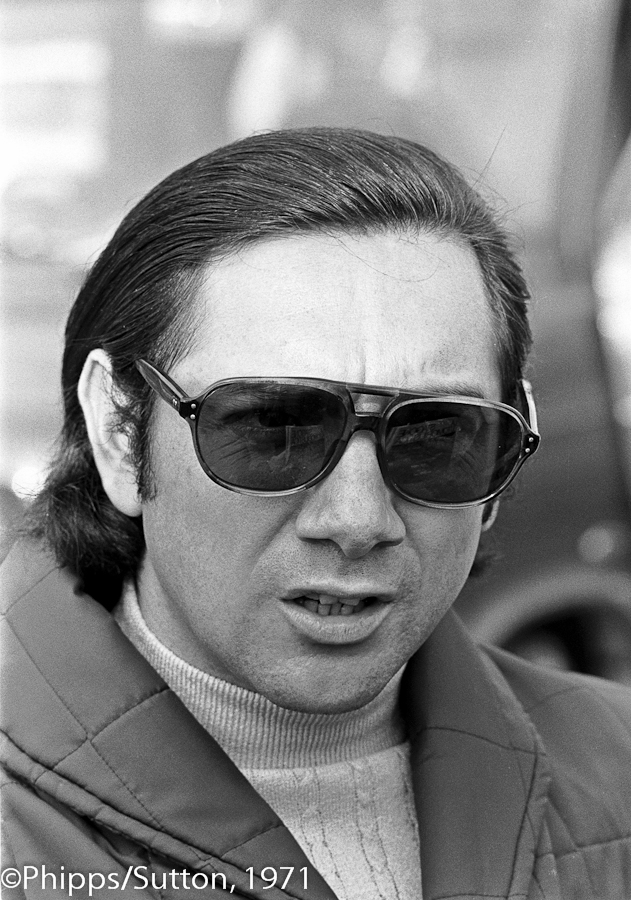

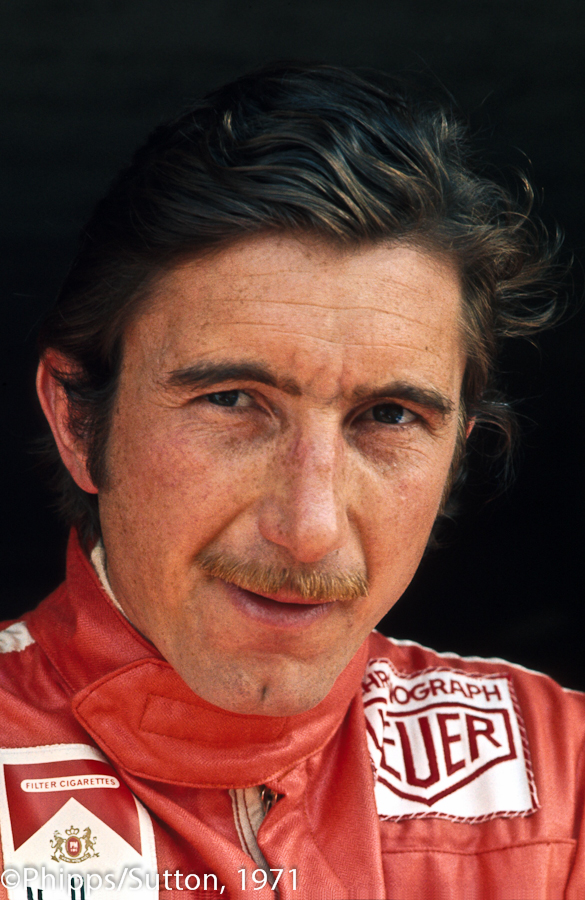

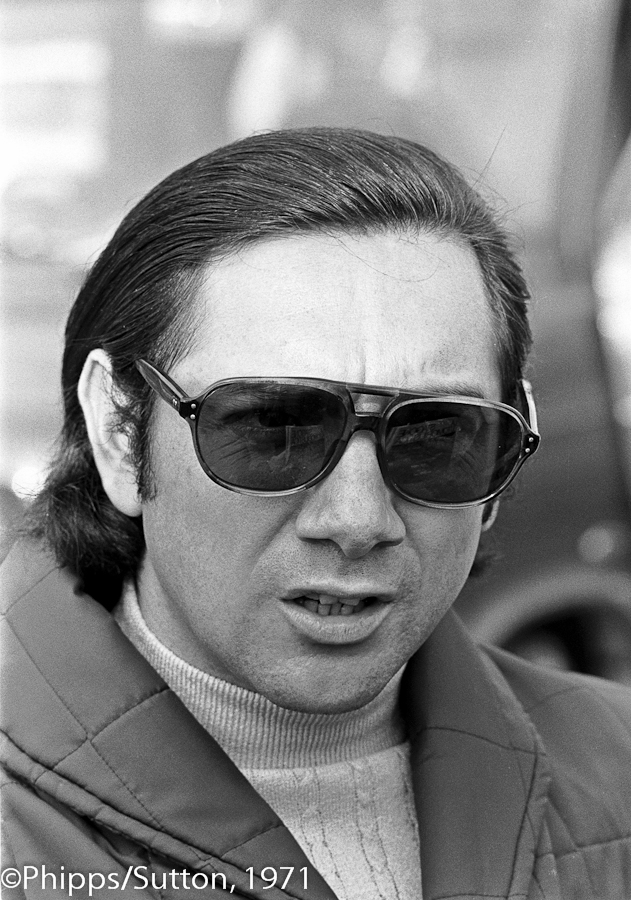

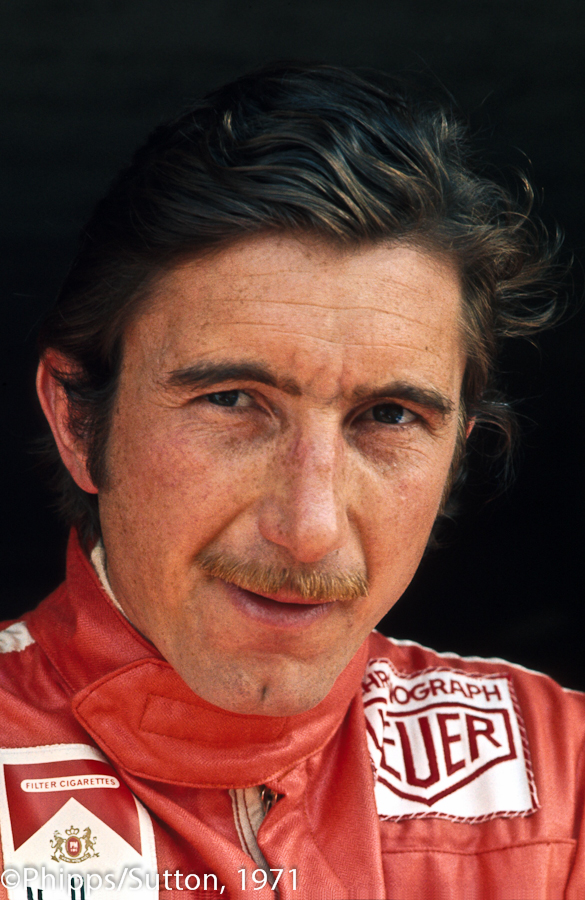

Everyone has heroes, especially when we are younger, they are those that we look up to and imagine that one day, we too might acquire some of the qualities that we admire. Back then my heroes were two drivers, Jo Siffert and Pedro Rodriguez, I was inspired by their performances in arguably the greatest sportscar of them all, the Porsche 917. I would read the race reports, especially in Motor Sport, from Denis Jenkinson, Michael Cotton and Andrew Marriott, the last two I would later become friends with. I simply HAD to go and see these guys race that year, the situation was given an urgency by the crazy decision of the FIA (where have we heard that before?) to scrap the 917s and 512s. There was only one solution, as I was too young to drive, I would get the train and bus to Brands Hatch. It was only on the other side of London.

March Hare

The calendar in 1971 had several international races held at the fantastic Kent track. First up for me was the Race of Champions. Back in the dark ages BE (Before Ecclestone), there were non-Championship Formula One races, so you could get to see the Grand Prix circus several times in a season, especially if you lived in England. OK, not all the F1 regulars turned out but that was also the case at some Grand Prix, especially the far flung ones, there was no FOCA package back then. One thing that has not really changed in 40 years is the grim weather, cold, damp and grey, that bit of Brands Hatch in March remains a constant. The front row had Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell on pole with Denny Hulme alongside in his McLaren and completing the line up was Clay Regazzoni in the delicious Ferrari. There were former and future World Champions Graham Hill, John Surtees and Emerson Fittipaldi in the field but my two heroes were missing, both on Gulf 917 duty at Sebring. A couple of things stuck in my mind from that race, the variety of noses on the cars with wild variations ranging from the Brabham BT34 “lobster claw” to the March 711 “tea tray”, did any of them really work? That day also saw the début of the Lotus 56B powered by a Pratt & Whitney gas turbine, one of Colin Chapman’s ideas that worked as an Indianapolis 500 car but was not suited to the Formula One world. I cannot remember much about the race, except that Ferrari and Regazzoni won it.

Gloria in Excelsis Deo

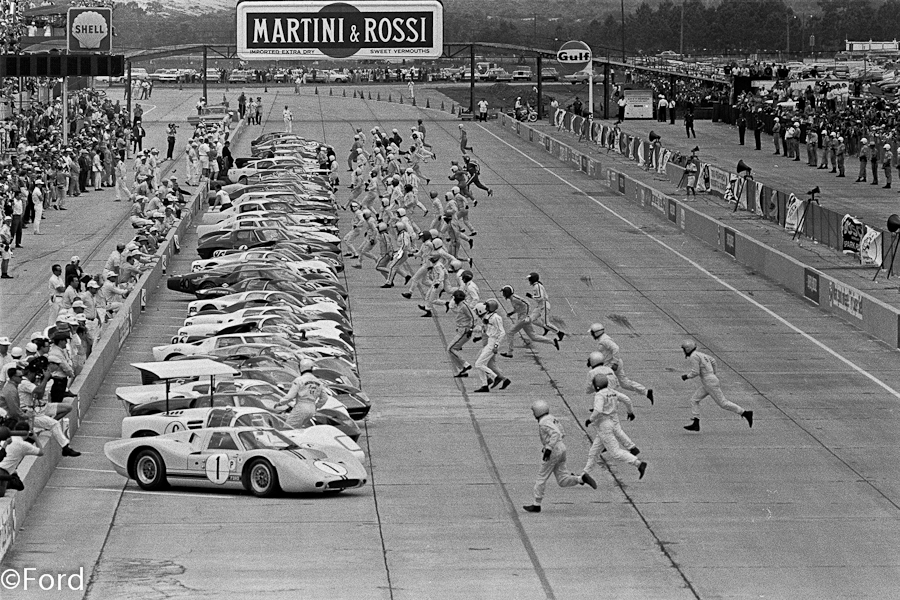

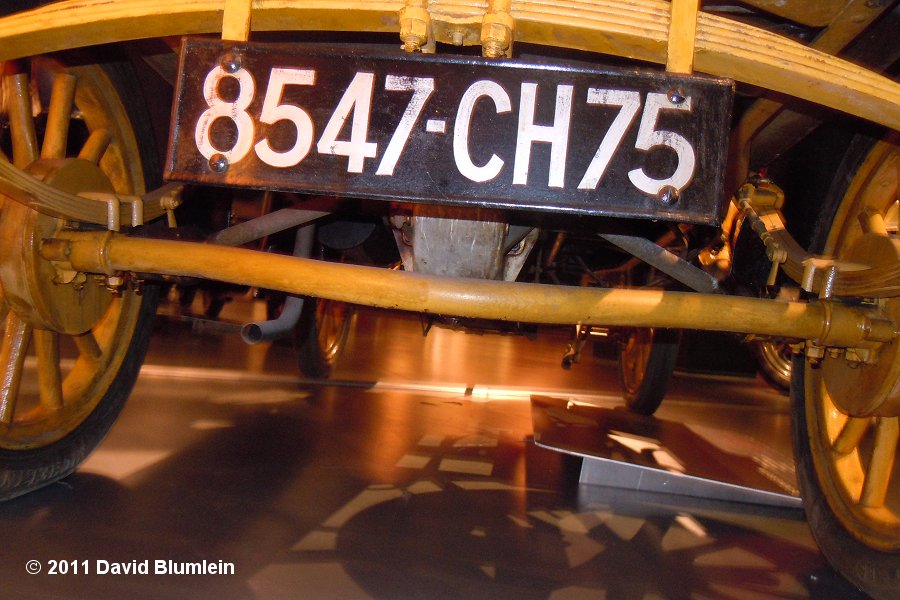

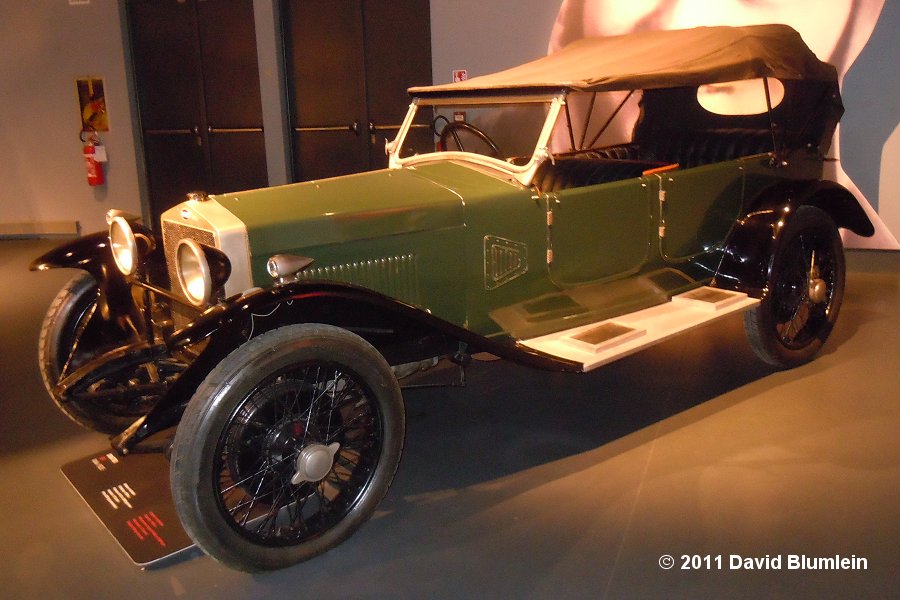

A few weeks later and I was back at Brands Hatch for the BOAC 1000 Kilometres, now I would get to see both Siffert and Rodriguez and the Gulf Porsche 917s. These guys would see off the opposition for sure, but as I would find out, life is not that simple. The weather was similar to the previous race and near freezing point. I thought, perhaps it is always like that in Kent. The field was a bit thin, frankly. The pair of Gulf 917s were backed up by two Martini & Rossi cars and privately entered 1970 spec 917. Against this line up was a lone Ferrari 312P and a brace of Alfa Romeo T33/3s run by Autodelta. Even I could see that the rest of the field of upgraded 512Ms and 2-litre prototypes would have real chance in the race.

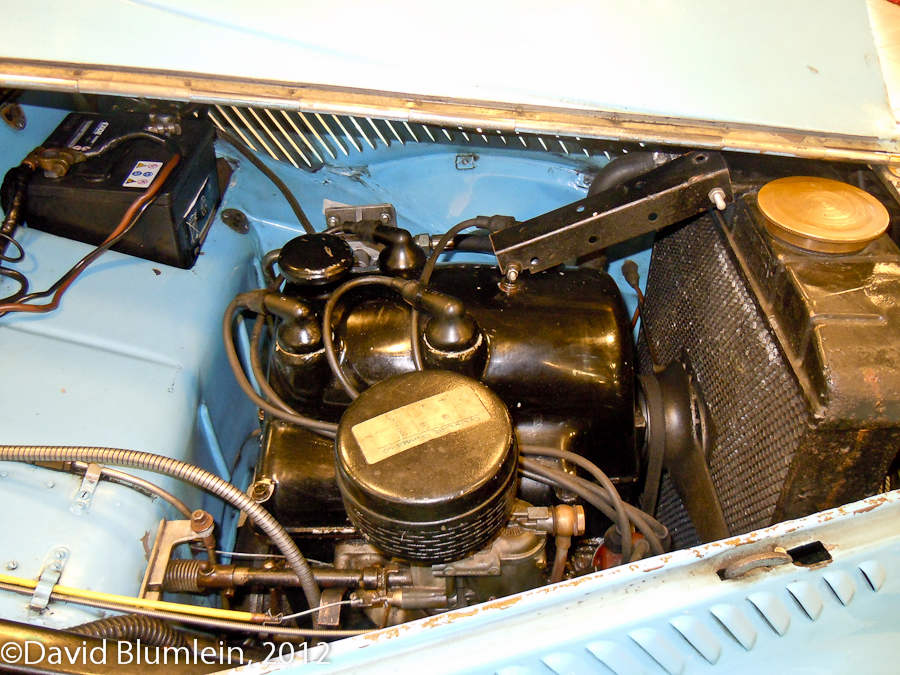

T33/3

Midday saw the race get underway and immediately my version of the script was proved wrong, with Ickx and the Ferrari taking the lead with the two Blue & Orange 917s in pursuit from the Alfa Romeos. Soon the natural order of things was restored as the Ferrari disappeared for several laps leaving the Mexican star leading his Swiss team mate, this was more like it. Then after an hour or so I went tramping around the track and noticed that the #7 Porsche was missing, after a while I found it parked up at Dingle Dell. I read later that the fuel filter had been clogged up with debris from an experimental pit refuelling system that the team were trying for the first time. Siffert too was having problems with changing tyres, an new alloy hub had expanded meaning that getting the nuts undone and done became almost impossible. JW Automotive had comprehensively shot itself in both feet. The upshot of all this was to hand Alfa Romeo its first international motorsport victory in 20 years. It looked as if Rolf Stommelen and Toine Hezemans, with a lap advantage over Andrea de Adamich and Henri Pescarolo, would be the heroes for Autodelta but the race had one final twist. A suspected piston failure halted the leading T33/3 in a cloud of smoke. Some 30+ years later I was enjoying the company of Hezemans, father and son, in a bar, where else? I happened to mention to Toine about seeing him all those years before at Brands Hatch. His answer was a stream of invective directed at Carlo Chitti, who he blamed for all the car’s problems, the competitive fires still burn. Of course being Toine this was also very funny, being almost paralysed with the combination of beer and laughter is the only thing I can recall from that evening. Long may he go on.

Champion

I had seen the Men and the Machines but there had been no fairy tale victory. Indeed things would take a very dark course for the rest of the year. The British Grand Prix was due to be held at Silverstone and I had persuaded a neighbour to let me come along with him. The BRMs that both Rodriguez and Siffert drove were competitive that season, arguably the last year that could be said. So I was really looking forward to seeing them take the fight to Jackie Stewart. Of course that did not happen, Pedro had decided to accept a drive the weekend before in Herbert Müller’s Ferrari 512 at the Norisring. Early in the first race a front tyre punctured, the Ferrari went out of control and hit a concrete wall. The impact destroyed the car and Pedro died soon after from the injuries received in the accident. Back then there was no internet, no TV news channels, so I did not hear anything about the death of the Mexican till a few days later when I was back at school, it was very unreal, unbelievable. Of course it was very real and all too believable. Two BRMs lined up at the Grand Prix instead of three and I had almost lost interest in the proceedings. It was a dull race dominated by Jackie Stewart but at least it was a proper summer’s day at Silverstone. No Pedro though.

P160

Later that summer the news arrived regarding the cancellation of the Mexican Grand Prix due to be run in October. A replacement event was put together, The Rothmans World Championships Victory Race, to be held at, yes, Brands Hatch. Another chance to see Formula One, in my back yard, this race was to be held in the honour of the new World Champions, Jackie Stewart and Tyrrell. Jo Siffert had stepped up to the plate after the death of his team mate and had won the Austrian Grand Prix, as well as taking the lead role in Porsche’s Can-Am campaign. So he was one of the favourites for the last race of the year and indeed started from pole position. My mate James and I made another journey by train and bus to arrive in time for the race. We wondered over to South Bank to the point where the cars head out of the stadium onto the Grand Prix loop. It was a beautiful sunny day, generally a good way to sign off a difficult season. When the cars reached us on the first lap, a BRM was leading but the helmet was a dark blue and not the red and white of the Swiss flag, it was Peter Gethin not Jo Siffert. The Swiss driver had a problem at the start and was down in 9th place. Gradually he climbed through the field up to 4th, then on lap 15 he accelerated away out our sight and never came back. It is thought that the rear suspension had failed at Pilgrims Drop, pitching the car into a bank where it rolled and collected a marshals’ post and then it exploded in flames. Attempts to rescue the unfortunate Siffert failed and he was asphyxiated in the delay, his only other injury was a broken ankle.

From our viewing point at the bottom of the circuit we could see nothing but it was clear that something was very wrong. We were advised that racing was done for the day (it was not) and to go home. So we trudged to bus stop and joined the queues, over 40,000 had turned out that day. I still had no idea what had happened until arrived back at my house, my father broke the news to me. Another bad day.

Is it not passing brave to be a King, and ride in Triumph through Persepolis?

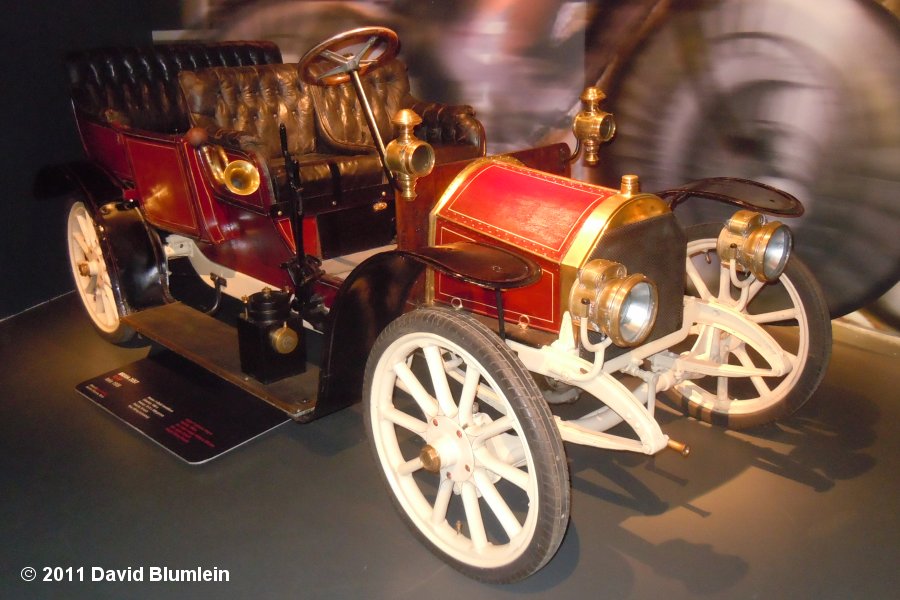

The year ended with death of my two heroes and the end of the endurance career of the Porsche 917. I have to admit that my interest in the sport dipped for a while as I struggled to understand the events of 1971, but motorsport is like a drug, once you are hooked you never really get over it. The year had seen the release of the film “Le Mans” which of course I had to see, and I did several times. The 917s and 512s, the stars, Le Mans, and some of the greatest action footage ever shot. The ACO should thank Steve McQueen every day that the sun rises, the coolest guy on the planet made the coolest movie about the coolest race. Even the sparse dialogue contained some philosophy that helped me to understand the motivation of drivers like Siffert and Rodriguez, in the face of almost certain death or injury.

“A lot of people go through life doing things badly. Racing’s important to men who do it well. When you’re racing, it… it’s life. Anything that happens before or after… is just waiting.”

Michael Delaney’s words struck a chord with me, perhaps such a simple statement could explain why I am still chasing the sport some 40 years later. On balance I think I took the right road back then, there has been no looking back.

Seppi

John Brooks, February 2012