I wrote this retrospective a while back, intending it to be used for another purpose. Perhaps it should have seen the light of day last weekend when the attention of the GT Universe was focused on Francorchamps. It matters not, like the 2019 edition the 2009 Spa 24 Hours was action packed, this part of Belgium rarely disappoints. So take a few minutes to look back to the time of GT1………….

Change was in the air for those anticipating the 2009 edition of the Spa 24 Hours. In early July that year the FIA had given approval for SRO’s next big step, the FIA GT1 World Championship, a brave venture to launch in the face of the financial storms that were raging at the time. This bold move also spelled the end of the road for the FIA GT Championship which had graced tracks around the globe since 1997, taking GT racing to new heights.

The 2009 Spa 24 Hours would therefore be the last contested by the GT1 cars that had pretty much ruled the roost since 2001 when SRO took over as promoters of the Belgian endurance classic. That fact combined with the economic challenges of the time faced by all the competitors meant that the field in the leading class was smaller than in previous years. However, the quality of the competitors more than made up for any shortfall in quantity.

Hot pre-race favourites were the trio of Maserati MC12 GT1s entered by Vitaphone Racing, as winners in three of the previous four years at Spa, they looked on course to add to their trophy cabinet. The German team’s driver line ups were first class too. In #1 were the reigning FIA GT Champions, Andrea Bertolini and Michael Bartels with Stéphane Sarrazin and Alexandre Negrão completing the quartet. #2 MC12 had regulars Alex Müller and Miguel Ramos supported by Pedro Lamy and Eric van de Poele, a record five-time winner at the Spa 24 Hours. The final Vitaphone entry had Belgians Vincent Vosse and Stéphane Léméret leading the charge with Carl Rosenblad and Alessandro Pier Guidi also in the team.

The opposition to the Italian supercars came in the shape of three Corvette C6.Rs. Local favourites Peka Racing Team gave the crowds something to shout about and did not lack in speed and experience in the driver department with a line-up of Mike Hezemans, Anthony Kumpen, Jos Menten and Kurt Mollekens. Race day would be Mike’s 40th birthday, what better present than a second triumph at the Spa 24 Hours?

Bringing a touch of the exotic to the grid was the C6.R of Sangari Team Brazil. The car, formerly run under the DKR banner, was crewed by ex-F1 driver Enrique Bernoldi and his fellow Brazilian Roberto Streit, with Xavier Maassen the third driver.

The final Corvette on the grid was entered by Selleslagh Racing Team, long-time supporters of the Championship. Leading their challenge was Vette factory driver and all-round good egg, Oliver Gavin. His teammates were James Ruffier, Bert Longin and Maxime Soulet.

The brave new world of the future GT1 class was also represented on the grid with the Marc VDS Ford GT and a factory backed Nissan GT-R. While these novelties attracted much attention, they were considered too new to challenge for outright victory.

The Qualifying sessions were struck by rainstorms of biblical proportions and there was virtually no running in the dry. The grid lined up with the Vitaphone Maseratis at the head with the Sangari and Selleslagh C6.R pair up next. Then it was the Marc VDS Ford, the final Vette of Peka Racing and the GT1 field was rounded out by the Nissan.

The Maserati phalanx immediately grabbed the lead on the run down to Eau Rouge and headed the field on the climb up the Kemmel Straight to Les Combes. If the MC12s thought that they would dominate the race they soon disabused of that notion. Within seven laps it was a Corvette 1-2, with Bernoldi heading Gavin, while Hezemans was also on the way up the leader board. However, the weather gods decided to get in on the act and soon heavy rain was falling and that seemed to favour the Maseratis.

For the first two hours the race swung between the leading six cars, then Streit’s Corvette crashed heavily at Raidillon and was out of the race. The rain returned with a vengeance after that with the contest potentially being won and lost in the pits as much as on track. Getting the right tyre strategy was vital to keeping up the pace, the engineers were as stressed as the drivers. The lead continued to change until just after Midnight when Bertolini lost control of his MC12 after encountering oil all over the track at Pouhon. He managed to get the heavily damaged car back to the pits but the repairs would take three hours and cost 67 laps. It later emerged that Hezemans was following the Maserati closely and also spun on the oil but without making contact with anything, that really was a late birthday present.

The problems at Vitaphone piled up when Pier Guidi was hit by a backmarker not long after the Bertolini incident. The subsequent repairs took ten laps and banished any realistic prospect of victory. Meanwhile out on track a fantastic battle raged in the darkness between Gavin, Hezemans and Lamy. This contest continued when Soulet, Kumpen and Müller took over their respective mounts at the next set of pitstops.

The rain gradually disappeared and as dawn broke the remaining Maserati began to slowly edge away from the chasing Corvette pair, although a mighty stint from Gavin yielded the fastest lap of the race, 2:15.423, and kept his Vette in contention. Then just after 10.00am disaster struck Müller in the MC12 when the Maserati’s rear right wheel collapsed approaching Fagnes, damaging the suspension. Despite his best efforts Müller could not get the three-wheeler back to the pits and was forced to retire on the spot.

The race had one more act of motoring cruelty to inflict, this time on the Selleslagh Corvette. A breather pipe worked loose, the loss of oil damaged the engine and the team parked the car in anticipation of completing one slow lap at the finish, being classified and scoring points would be scant reward for their efforts battling for the lead.

The final three hours of the race played out without drama at the head of the field till Kurt Mollekens crossed the line to score a popular and famous victory. The Peka Racing Corvette hardly missed a beat, the only one of the leading contenders to do so. Eleven laps down, and in second place, was the recovering #33 Maserati, but bitter disappointment would be all that Vitaphone Racing would take away from Spa.

The final step of the podium was taken by Phoenix Racing’s Audi R8 LMS which was running in the G2 class. The crew, Marcel Fässler, Marc Basseng, Alex Margaritis and Henri Moser had a largely trouble free run. The performance of the Audi gave a clue as to the future direction of the Belgian classic. The Audi was essentially a GT3 car, the race would prosper under that formula when it was adopted for the 2011 event. The fantastic entry for this year’s race is proof of that.

GT1 has signed off at the Spa 24 Hours in the most dramatic fashion, now there was a World Championship to chase.

John Brooks, August 2019

Autumn or Fall as the locals would say is a very agreeable time to be in California’s Monterey Peninsula. This weekend the 2018 Intercontinental GT Challenge will reach its climax after a season of classic endurance GT races. SRO has history at the fantastic Laguna Seca track dating back to its earliest days.

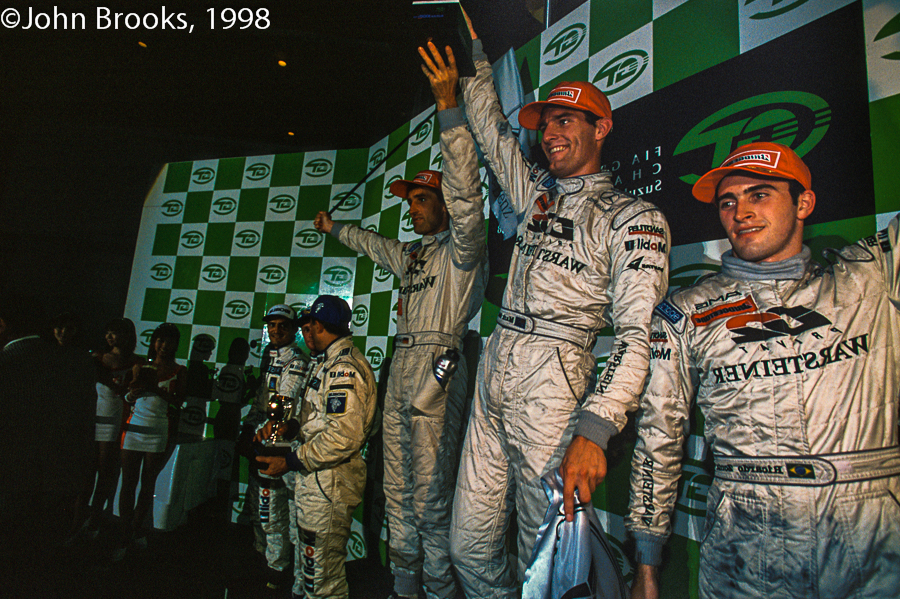

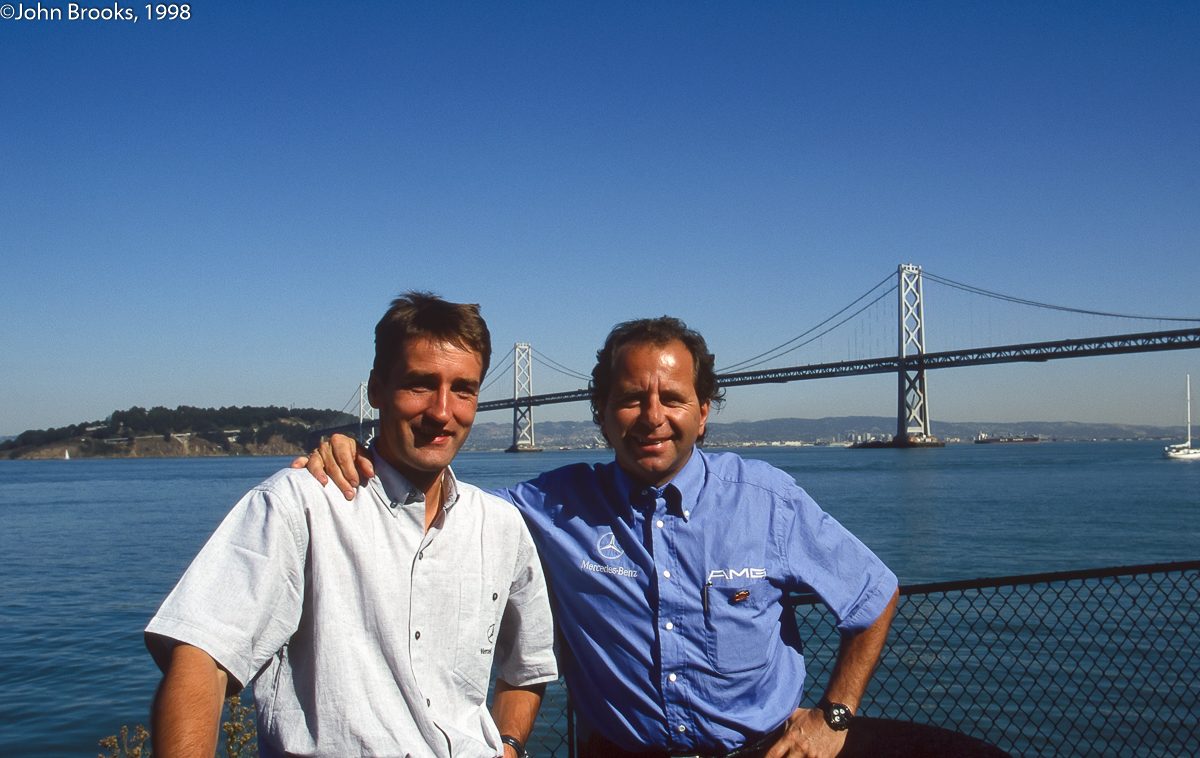

Autumn or Fall as the locals would say is a very agreeable time to be in California’s Monterey Peninsula. This weekend the 2018 Intercontinental GT Challenge will reach its climax after a season of classic endurance GT races. SRO has history at the fantastic Laguna Seca track dating back to its earliest days.  Some 20 years ago the final round of the 1998 FIA GT Championship, was held at Laguna Seca. In the top GT1 class it was scheduled to be a classic encounter between the veteran champion, Klaus Ludwig and the bright star emerging to ascendancy, Bernd Schneider. Yes of course they had co-drivers, Ricardo Zonta and Mark Webber, but despite the obvious talent and potential of that pair all eyes were on the two Germans of different generations. Schneider had taken the title in 1997 and had looked favourite to repeat this for most of the 1998 season.

Some 20 years ago the final round of the 1998 FIA GT Championship, was held at Laguna Seca. In the top GT1 class it was scheduled to be a classic encounter between the veteran champion, Klaus Ludwig and the bright star emerging to ascendancy, Bernd Schneider. Yes of course they had co-drivers, Ricardo Zonta and Mark Webber, but despite the obvious talent and potential of that pair all eyes were on the two Germans of different generations. Schneider had taken the title in 1997 and had looked favourite to repeat this for most of the 1998 season. What added spice to the contest was that they were both driving for the AMG Mercedes team, for the majority of the season in the all-conquering Mercedes-Benz CLK-LM. Approaching the decisive race, the score sheet showed Ludwig and Zonta ahead of their rivals by four points, the margin between first and second place on track. However, Schneider and Webber had racked up five wins to four, so if the points tally was equal after Laguna Seca they would be champions on the basis of more race wins. It was a case of the winner takes it all and second place would be nowhere.

What added spice to the contest was that they were both driving for the AMG Mercedes team, for the majority of the season in the all-conquering Mercedes-Benz CLK-LM. Approaching the decisive race, the score sheet showed Ludwig and Zonta ahead of their rivals by four points, the margin between first and second place on track. However, Schneider and Webber had racked up five wins to four, so if the points tally was equal after Laguna Seca they would be champions on the basis of more race wins. It was a case of the winner takes it all and second place would be nowhere. The GT2 class was a complete contrast to this close contest in GT1. The Oreca Chrysler Viper team dominated proceedings, winning eight out of the nine rounds already run. Olivier Beretta and Pedro Lamy had grabbed the Drivers’ Title with seven victories, Monterey was expected to be more of the same. Could either the Roock Racing Porsches or Cor Euser’s Marcos challenge the Viper’s hegemony?

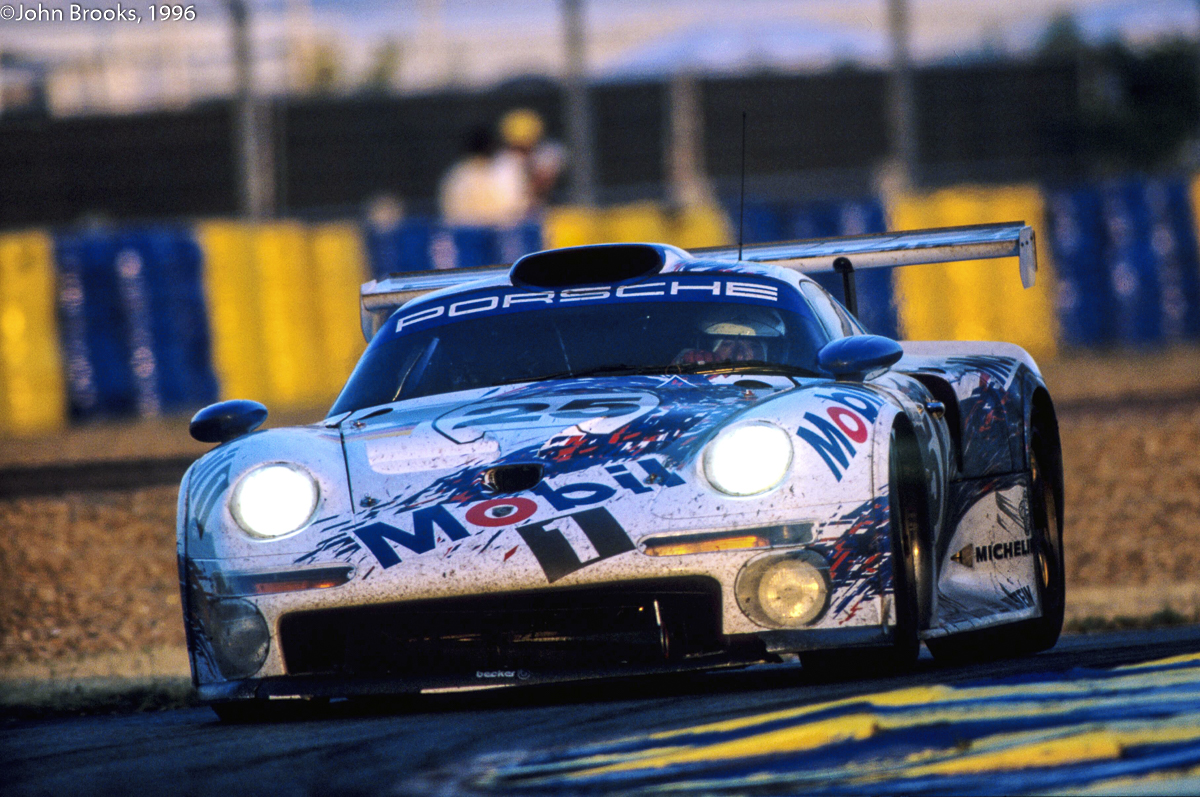

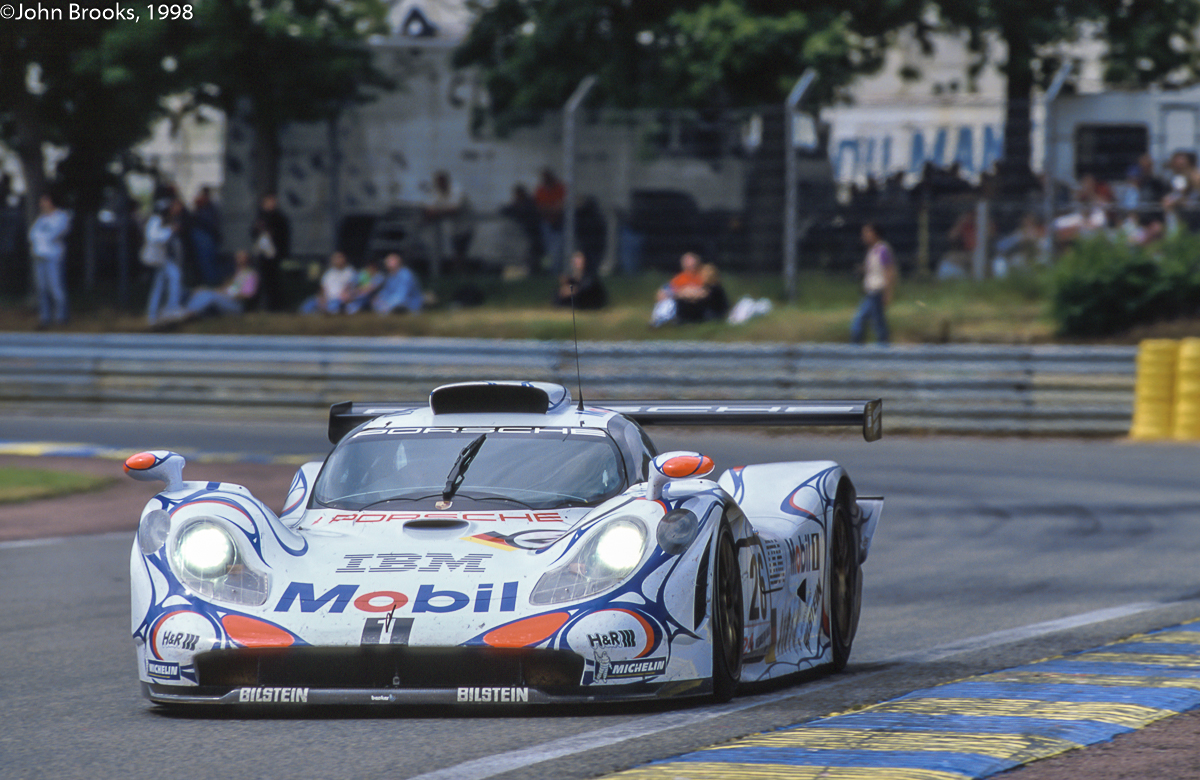

The GT2 class was a complete contrast to this close contest in GT1. The Oreca Chrysler Viper team dominated proceedings, winning eight out of the nine rounds already run. Olivier Beretta and Pedro Lamy had grabbed the Drivers’ Title with seven victories, Monterey was expected to be more of the same. Could either the Roock Racing Porsches or Cor Euser’s Marcos challenge the Viper’s hegemony? 1998 was an almost perfect season for the AMG Mercedes squad. The only hiccup had come during the Le Mans 24 Hours when both cars went out early after suffering engine failure. A seal in the power-steering hydraulic pump failed and that trivial fault fatally damaged the engine. It was a most un-Mercedes moment as otherwise they were in a different league to their closest and only serious competitor, Porsche AG’s 911 GT1 98.

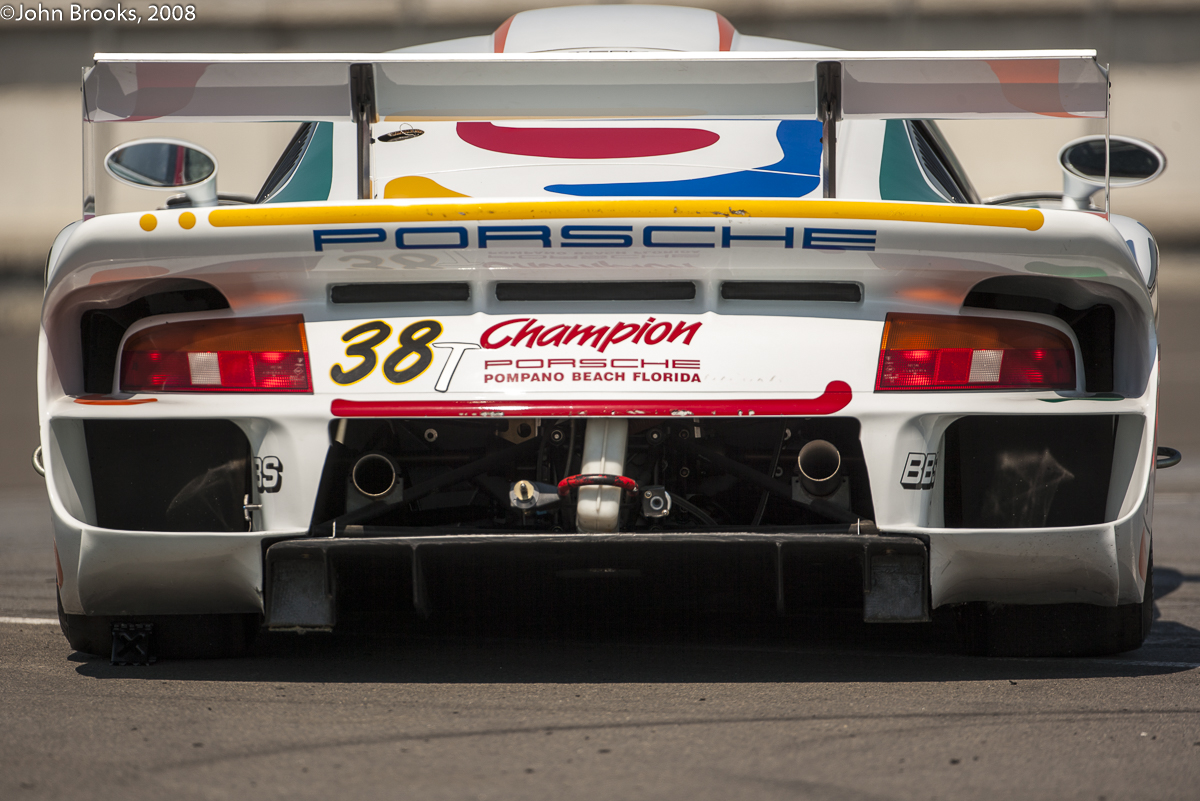

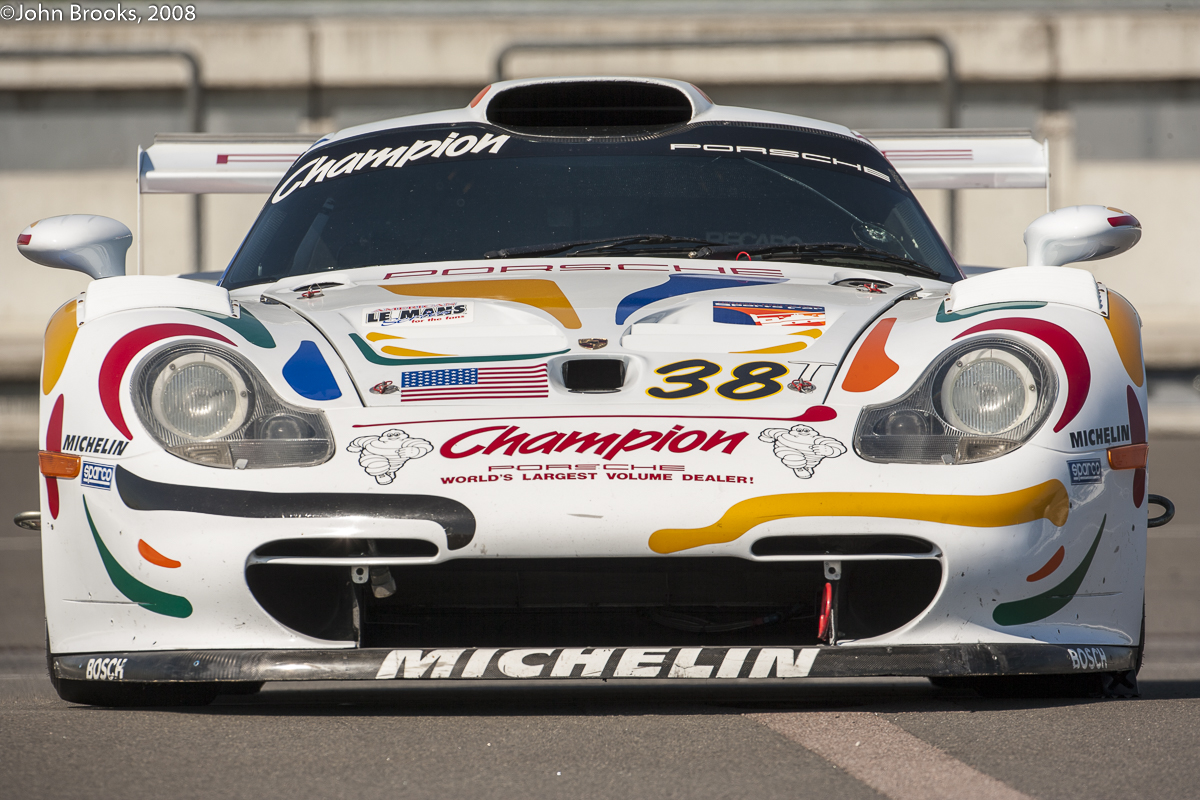

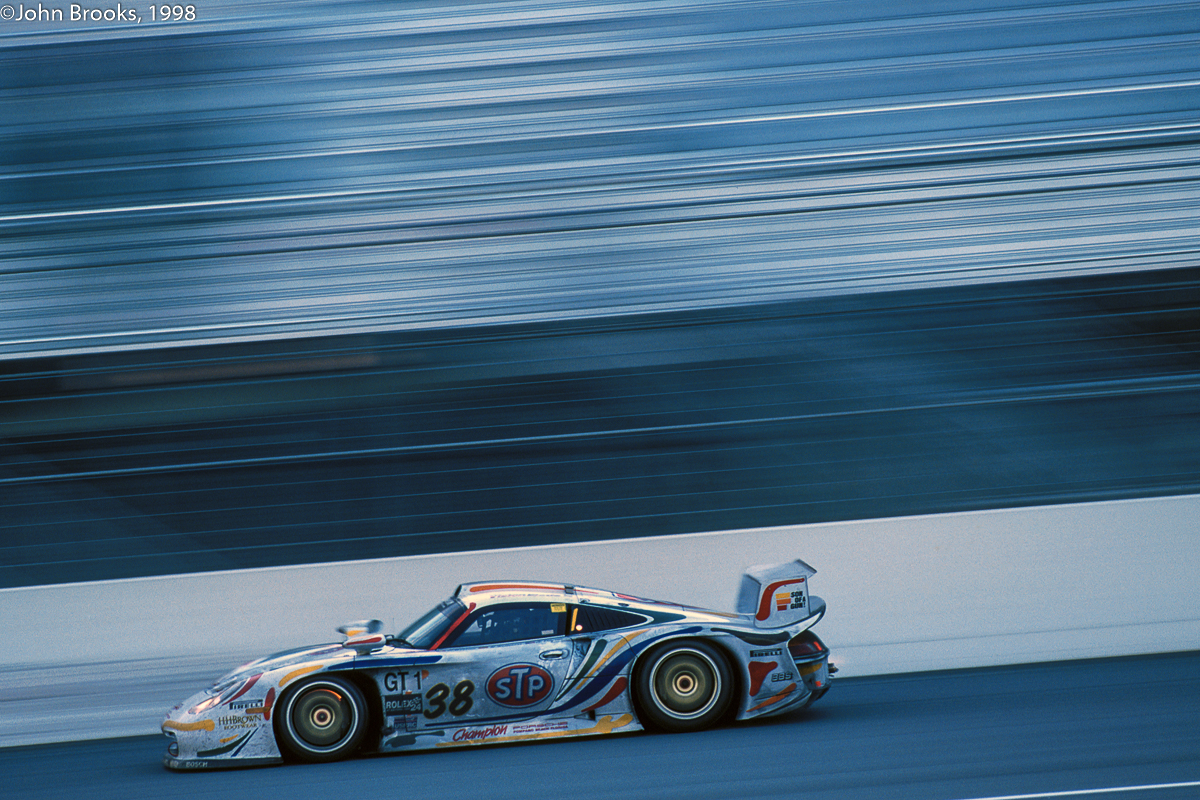

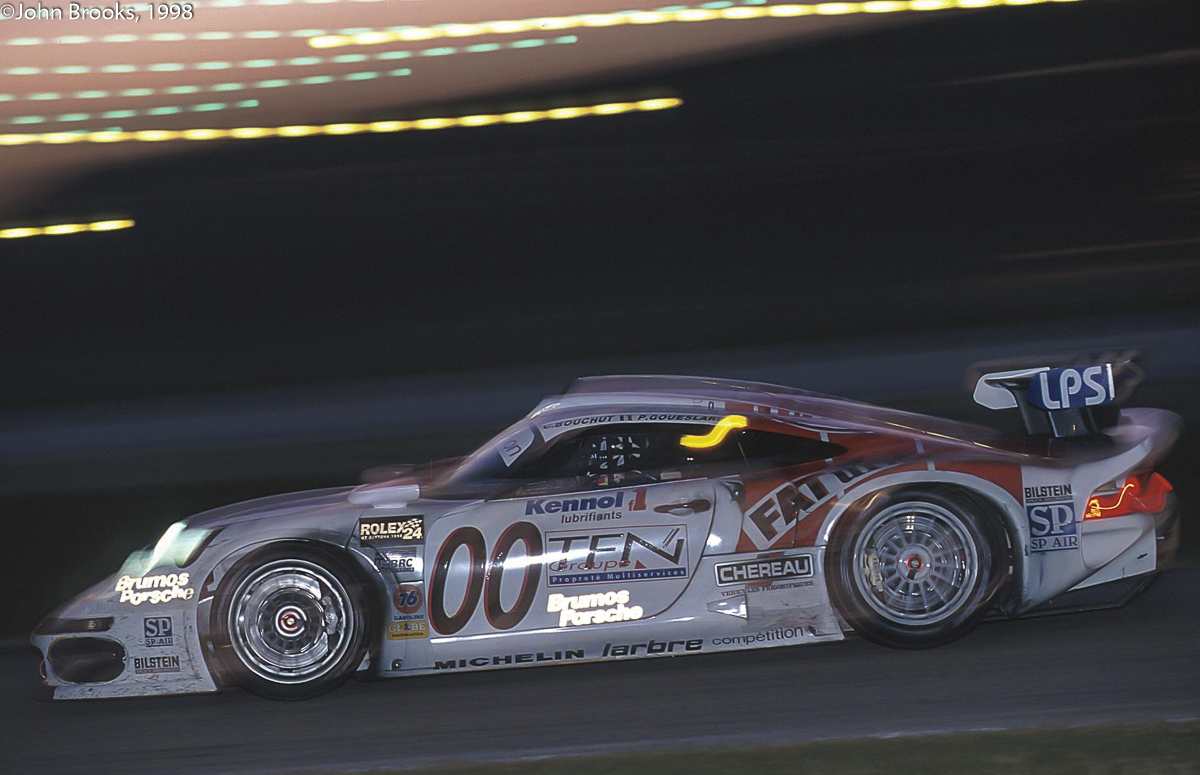

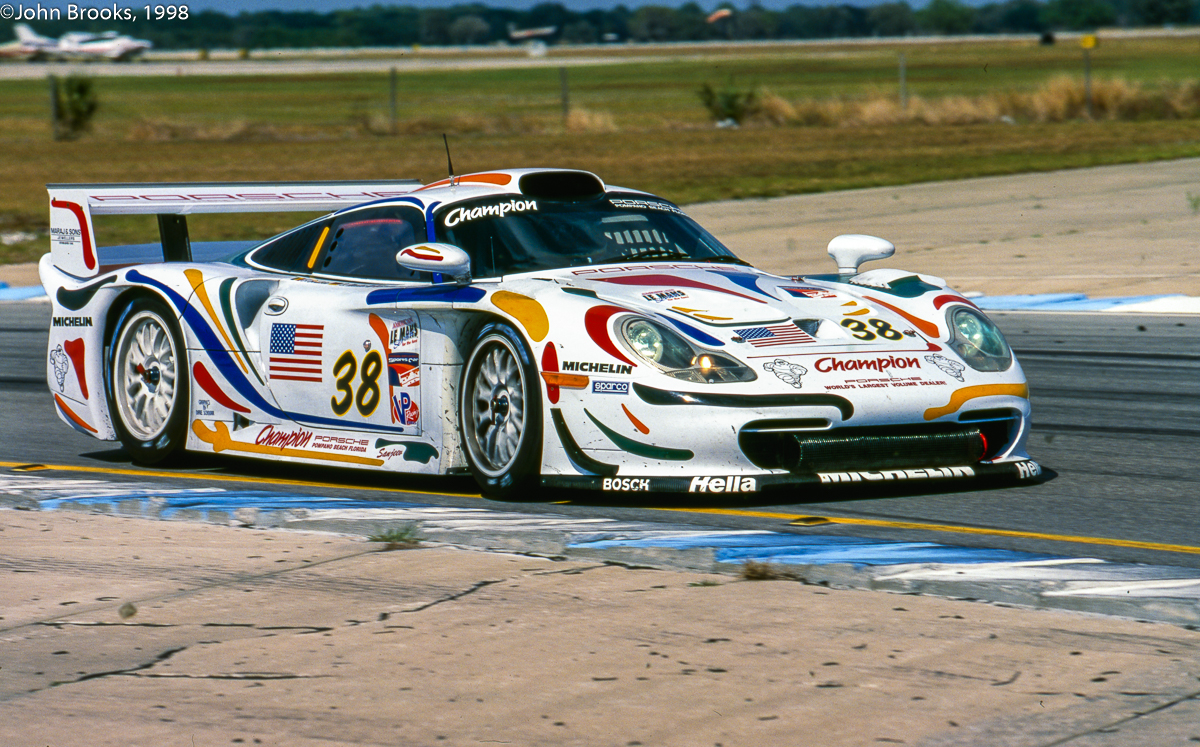

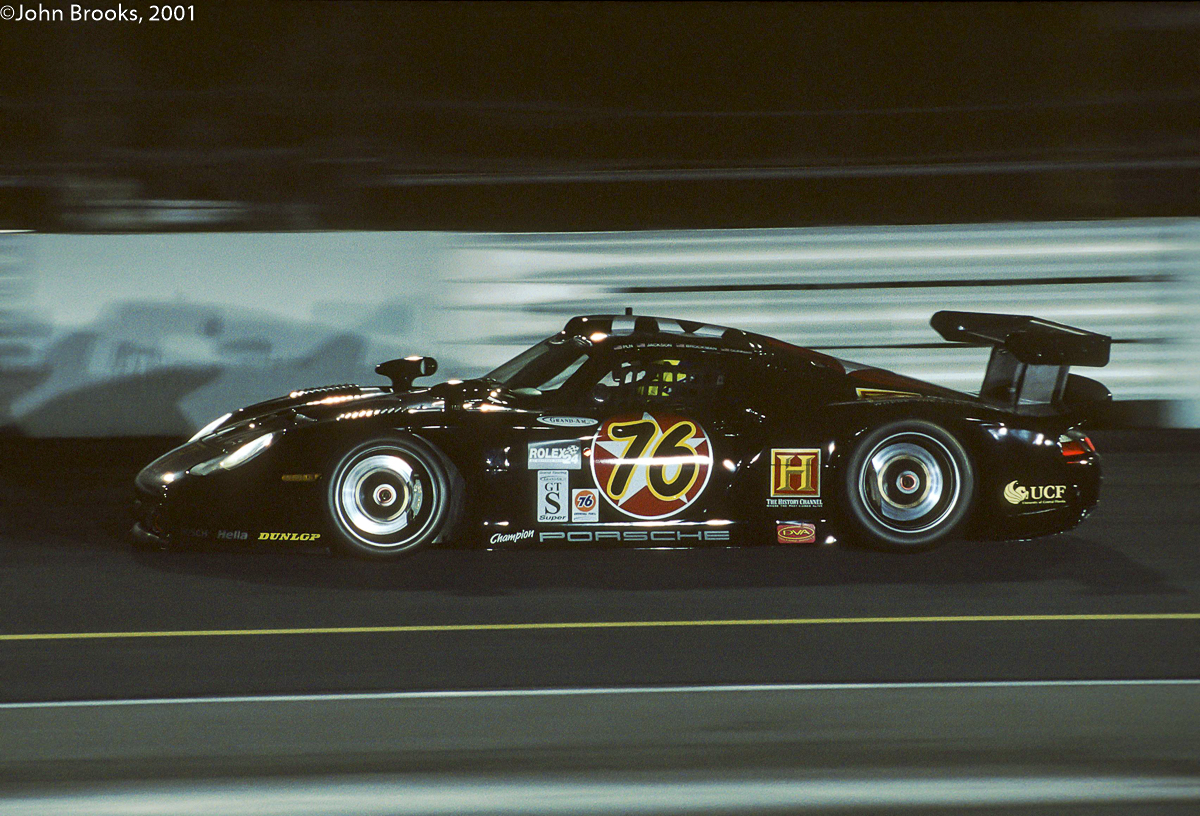

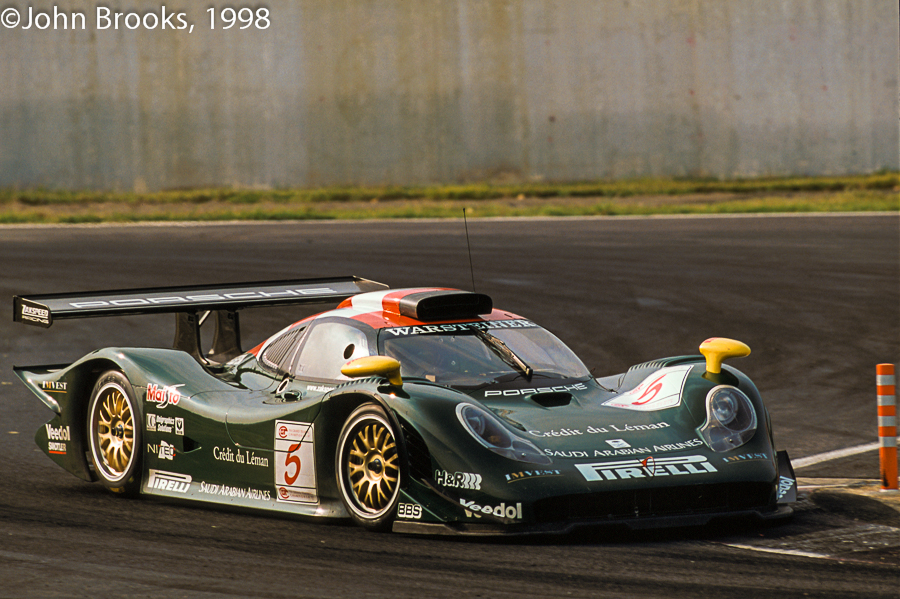

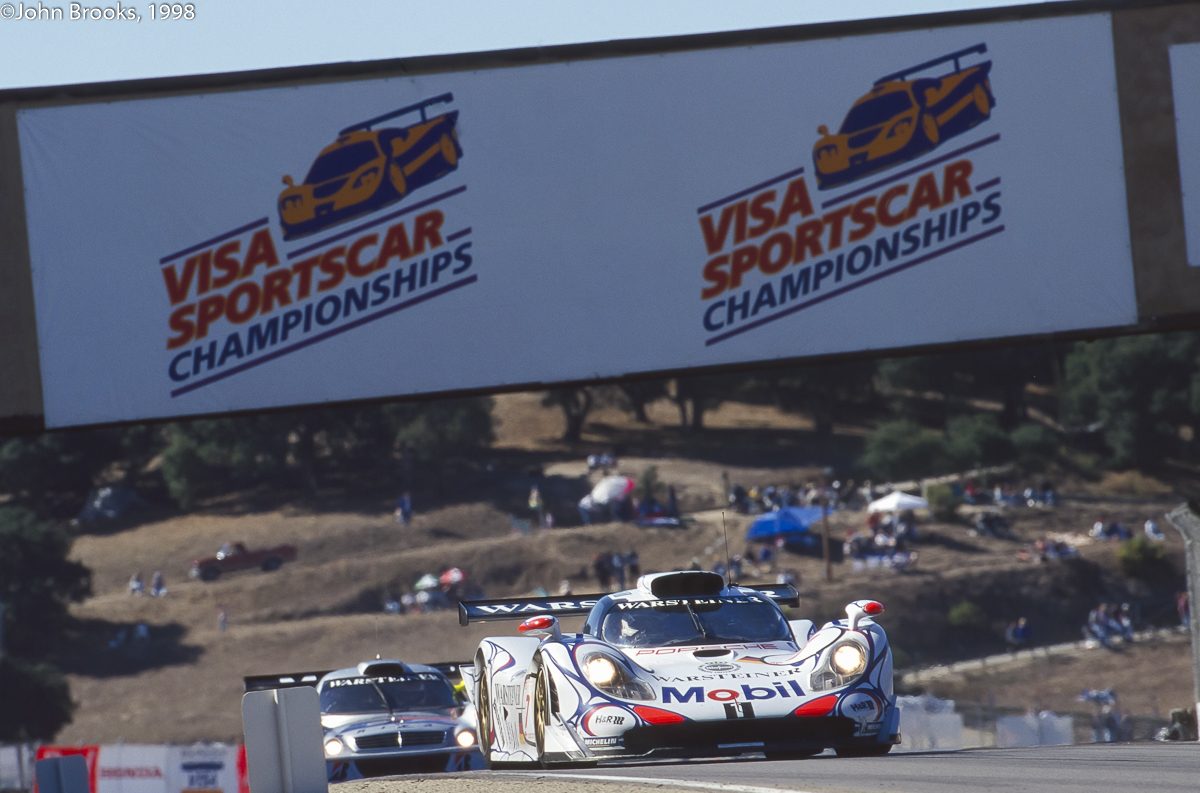

1998 was an almost perfect season for the AMG Mercedes squad. The only hiccup had come during the Le Mans 24 Hours when both cars went out early after suffering engine failure. A seal in the power-steering hydraulic pump failed and that trivial fault fatally damaged the engine. It was a most un-Mercedes moment as otherwise they were in a different league to their closest and only serious competitor, Porsche AG’s 911 GT1 98. In reality the Porsche was only a threat at certain kinds of circuits where the disadvantage of their turbocharged engines as regulated under the FIA GT1 rules package was not a factor. And even then, it was almost always Allan McNish who was able to challenge the Mercedes duo, we would grow accustomed to the electric pace of the Scot in the following decade, but it was something of an eye opener in 1998.

In reality the Porsche was only a threat at certain kinds of circuits where the disadvantage of their turbocharged engines as regulated under the FIA GT1 rules package was not a factor. And even then, it was almost always Allan McNish who was able to challenge the Mercedes duo, we would grow accustomed to the electric pace of the Scot in the following decade, but it was something of an eye opener in 1998. Adding even more spice to the contest was the announcement by Ludwig that he would retire from motor sport after the race in Monterey. His career had included three victories at Le Mans and five DTM titles, could he add the FIA GT Championship to the list? Klaus certainly was motivated, and said before the race, “Laguna Seca is one of the tracks I love the best. It’s a demanding track and an exciting track – the Corkscrew, in Europe, impossible! To win there would be very special for me.”

Adding even more spice to the contest was the announcement by Ludwig that he would retire from motor sport after the race in Monterey. His career had included three victories at Le Mans and five DTM titles, could he add the FIA GT Championship to the list? Klaus certainly was motivated, and said before the race, “Laguna Seca is one of the tracks I love the best. It’s a demanding track and an exciting track – the Corkscrew, in Europe, impossible! To win there would be very special for me.”  Ludwig was not the only one departing the GT scene, Ricardo Zonta was bound for Formula One, another Brazilian on the conveyor-belt of talent that started with Emmerson Fittipaldi and continued through Piquet, Senna, Barrichello and Massa amongst many others.

Ludwig was not the only one departing the GT scene, Ricardo Zonta was bound for Formula One, another Brazilian on the conveyor-belt of talent that started with Emmerson Fittipaldi and continued through Piquet, Senna, Barrichello and Massa amongst many others. However, there was still a Championship to be decided. Most Europeans like myself imagine that California is a place of sunshine and beaches, blondes and brunettes of either sex, all tanned, forever young. So, it was something of a shock arriving at the track in anticipation of Saturday Morning’s Qualifying session to conditions usually found at the Nürburgring or Spa, torrential rain. The first session was stopped after 15 minutes as a river of mud was blocking the Corkscrew, not quite how I imagined the weather would be on the West Coast.

However, there was still a Championship to be decided. Most Europeans like myself imagine that California is a place of sunshine and beaches, blondes and brunettes of either sex, all tanned, forever young. So, it was something of a shock arriving at the track in anticipation of Saturday Morning’s Qualifying session to conditions usually found at the Nürburgring or Spa, torrential rain. The first session was stopped after 15 minutes as a river of mud was blocking the Corkscrew, not quite how I imagined the weather would be on the West Coast. The afternoon’s conditions were much better and the advantage swung Ludwig’s way courtesy of Zonta. The Brazilian’s pole position lap of 1m16.154s was 0.434 seconds faster than Schneider’s best. Afterwards Ricardo explained. “My qualifying lap was really good but not without a problem. Because I experienced a little brake balance problem, I got off-line in the last corner where it was a little wet. That might have cost me some time.”

The afternoon’s conditions were much better and the advantage swung Ludwig’s way courtesy of Zonta. The Brazilian’s pole position lap of 1m16.154s was 0.434 seconds faster than Schneider’s best. Afterwards Ricardo explained. “My qualifying lap was really good but not without a problem. Because I experienced a little brake balance problem, I got off-line in the last corner where it was a little wet. That might have cost me some time.” In GT2 the Viper effort was reduced to one car after David Donohue crashed out on Friday. He hit the wall hard as a result of brake failure, the car caught fire and was too badly damaged for any immediate repair.

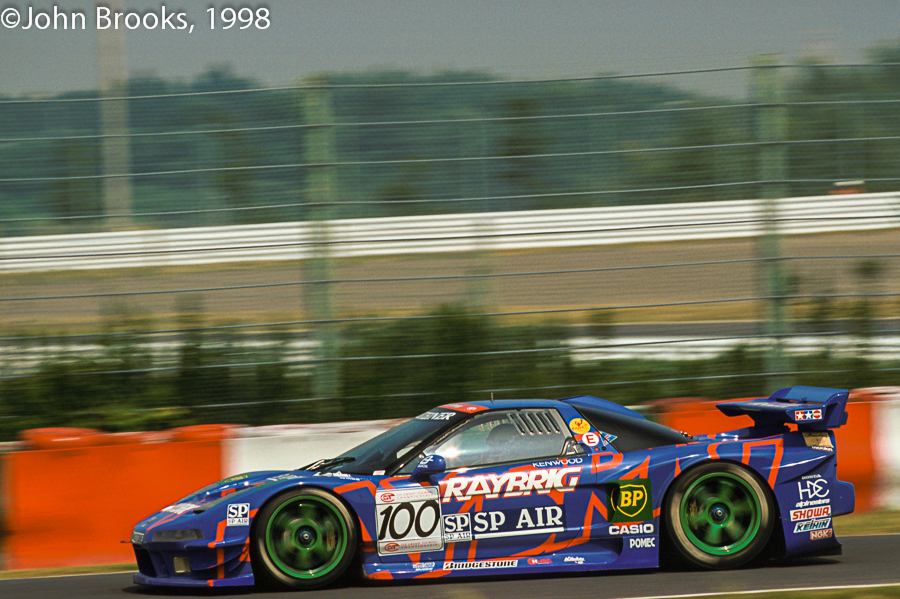

In GT2 the Viper effort was reduced to one car after David Donohue crashed out on Friday. He hit the wall hard as a result of brake failure, the car caught fire and was too badly damaged for any immediate repair. Class Pole was grabbed by a very determined Stéphane Ortelli in his Roock Racing Porsche 911 GT2 with a 1:24.851 lap, less than a tenth of second advantage over Cor Euser’s Marcos LM 600 who was fractions faster than Beretta’s Viper. This could be a race to match the GT1 battle, or so we hoped.

Class Pole was grabbed by a very determined Stéphane Ortelli in his Roock Racing Porsche 911 GT2 with a 1:24.851 lap, less than a tenth of second advantage over Cor Euser’s Marcos LM 600 who was fractions faster than Beretta’s Viper. This could be a race to match the GT1 battle, or so we hoped. After the traditional end-of-term drivers’ photo Klaus was presented with a lump of the track as a memento of his final race, it seemed a very Californian thing to do.

After the traditional end-of-term drivers’ photo Klaus was presented with a lump of the track as a memento of his final race, it seemed a very Californian thing to do. AMG Mercedes had the front row to themselves, who would emerge from Turn One in the lead, Schneider or Ludwig? Everyone held their breath but in the end the veteran got the best start and quickly pulled away from his rival.

AMG Mercedes had the front row to themselves, who would emerge from Turn One in the lead, Schneider or Ludwig? Everyone held their breath but in the end the veteran got the best start and quickly pulled away from his rival. In any case Bernd had his mirrors full of a Porsche with McNish making a nuisance of himself, even passing the Mercedes after a few laps.

In any case Bernd had his mirrors full of a Porsche with McNish making a nuisance of himself, even passing the Mercedes after a few laps. GT2 also saw a fierce tussle for the lead in opening laps before the natural order of things asserted itself with Beretta grabbing the lead. Two of the major challengers to the all-conquering Viper both retired with gearbox failure after just seven laps, that was the end of Jan Lammers in the Konrad Porsche and also Claudia Hürtgen in the 911 she shared with Ortelli. A few laps later and the Marcos was out. Also with transmission woes.

GT2 also saw a fierce tussle for the lead in opening laps before the natural order of things asserted itself with Beretta grabbing the lead. Two of the major challengers to the all-conquering Viper both retired with gearbox failure after just seven laps, that was the end of Jan Lammers in the Konrad Porsche and also Claudia Hürtgen in the 911 she shared with Ortelli. A few laps later and the Marcos was out. Also with transmission woes. Ludwig had his own dramas to contend with while negotiating his way through the traffic. William Langhorne in the Stadler GT2 Porsche was having a spirited contest with Michel Neugarten in his Elf Haberthur example, swapping positions round the sweeping track. The American was fully concentrating on the car in front so did not see Ludwig dive underneath him at Turn Three. The result was a heavy side impact that nearly put Klaus off the tarmac but somehow, he gathered himself together and raced on at full speed. Langhorne crashed out the following lap at the Corkscrew, something broke he maintained.

Ludwig had his own dramas to contend with while negotiating his way through the traffic. William Langhorne in the Stadler GT2 Porsche was having a spirited contest with Michel Neugarten in his Elf Haberthur example, swapping positions round the sweeping track. The American was fully concentrating on the car in front so did not see Ludwig dive underneath him at Turn Three. The result was a heavy side impact that nearly put Klaus off the tarmac but somehow, he gathered himself together and raced on at full speed. Langhorne crashed out the following lap at the Corkscrew, something broke he maintained. Schneider also got rid of the McNish problem around this point, the clutch failed on the Porsche stranding the Scot out on the far side of the circuit. It would be a straight fight for victory for the #1 and #2 Mercedes. Schneider then dived into the pits, fuel only, no fresh Bridgestones.

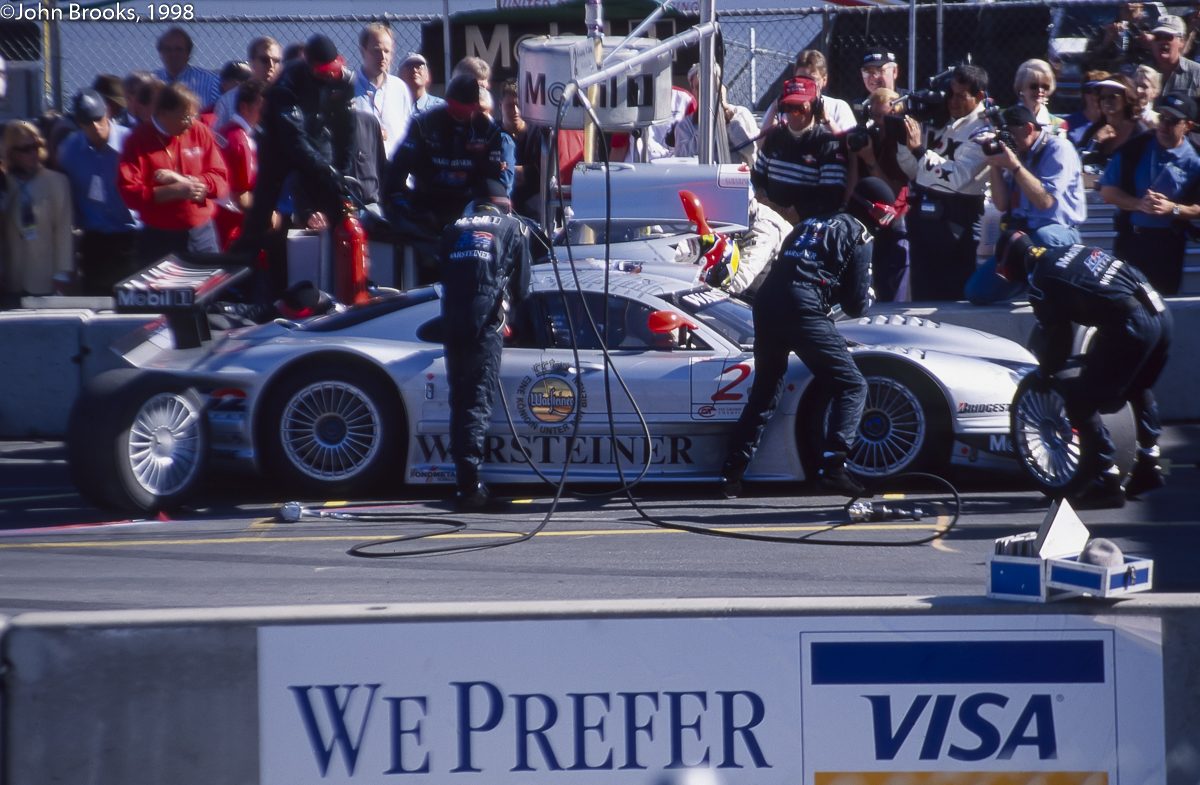

Schneider also got rid of the McNish problem around this point, the clutch failed on the Porsche stranding the Scot out on the far side of the circuit. It would be a straight fight for victory for the #1 and #2 Mercedes. Schneider then dived into the pits, fuel only, no fresh Bridgestones. A lap later Ludwig was in, then out of the car, Zonta taking new rubber. He managed to stall the CLK-LM as he left the pits, all of which gave a handy advantage back to Schneider.

A lap later Ludwig was in, then out of the car, Zonta taking new rubber. He managed to stall the CLK-LM as he left the pits, all of which gave a handy advantage back to Schneider. Bernd was looking certain to take the title but then lost a load of time stuck behind Jörg Müller in the other factory Porsche 911 GT1 98. Müller was determined to not go a lap down on the leader, hoping that the deployment of a Safety Car would give him the chance to catch up to the front. Eventually Müller ran wide at the first turn, allowing Schneider to pass, though he was furious at his fellow German. The gap was around the 12 second mark but this might not be enough to guarantee victory.

Bernd was looking certain to take the title but then lost a load of time stuck behind Jörg Müller in the other factory Porsche 911 GT1 98. Müller was determined to not go a lap down on the leader, hoping that the deployment of a Safety Car would give him the chance to catch up to the front. Eventually Müller ran wide at the first turn, allowing Schneider to pass, though he was furious at his fellow German. The gap was around the 12 second mark but this might not be enough to guarantee victory. The second stints ended and into the pits came Schneider to hand over to his Aussie co-driver who also received a new set of tyres. This would put Webber behind Zonta on the road as it was expected that his stop would be a fuel only affair and so it proved. The AMG Mercedes management had anxious moments after both of their cars left the pits for the final time. Both fell off the track at Turn Three where oil had been deposited by a back marker, both cars just missed hitting the wall by a fraction, it could have been a disaster.

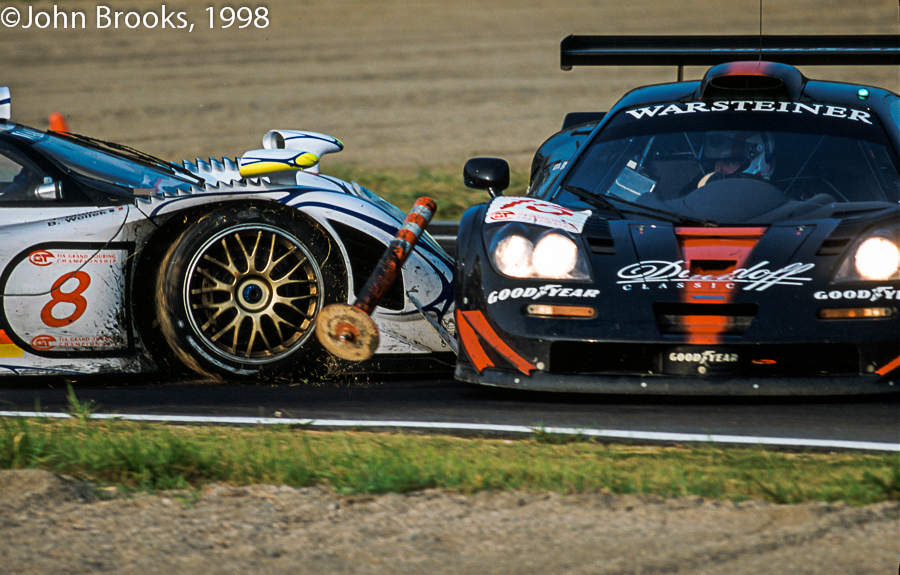

The second stints ended and into the pits came Schneider to hand over to his Aussie co-driver who also received a new set of tyres. This would put Webber behind Zonta on the road as it was expected that his stop would be a fuel only affair and so it proved. The AMG Mercedes management had anxious moments after both of their cars left the pits for the final time. Both fell off the track at Turn Three where oil had been deposited by a back marker, both cars just missed hitting the wall by a fraction, it could have been a disaster. Zonta had a lead of 16 seconds but Webber got his head down and chipped away taking a second here, a second there. The #8 Porsche intervened again, this time it was Uwe Alzen’s turn to hold up the #1 Mercedes for a lap or two. Eventually Weber dived down the inside at the first turn and once again the was contact as the Porsche was muscled out of the way but he was through and the chase was back on.

Zonta had a lead of 16 seconds but Webber got his head down and chipped away taking a second here, a second there. The #8 Porsche intervened again, this time it was Uwe Alzen’s turn to hold up the #1 Mercedes for a lap or two. Eventually Weber dived down the inside at the first turn and once again the was contact as the Porsche was muscled out of the way but he was through and the chase was back on. Webber posted a time of 1:19.094, setting a new GT record, would it be enough? The gap came down to ten seconds but the time ran out for the chasing Mercedes and Zonta crossed the line 10.8 seconds ahead – Ludwig and Zonta were Champions, the fairy tale had come true.

Webber posted a time of 1:19.094, setting a new GT record, would it be enough? The gap came down to ten seconds but the time ran out for the chasing Mercedes and Zonta crossed the line 10.8 seconds ahead – Ludwig and Zonta were Champions, the fairy tale had come true. There was no fairy tale in GT2, in fact the whole affair was something of a damp squib. The race was a walk over for Beretta and Lamy, who scored their eight class win of the season, ending up over a lap in front of the second Roock Racing 911 GT2, driven by Bruno Eichmann and Mike Hezemans. The final spot on the podium want to another 911 GT2, driven by Michael Trunk and Bernhard Müller.

There was no fairy tale in GT2, in fact the whole affair was something of a damp squib. The race was a walk over for Beretta and Lamy, who scored their eight class win of the season, ending up over a lap in front of the second Roock Racing 911 GT2, driven by Bruno Eichmann and Mike Hezemans. The final spot on the podium want to another 911 GT2, driven by Michael Trunk and Bernhard Müller. Schneider showed grace in defeat, he is, and always was, a class act. “Failing to win the title after 10 races by just 10 seconds shows how tough we raced for the Drivers’ Championship this season. Although Mark and I didn’t manage to win the Championship, I’m glad for the team. Congratulations to my old friend Klaus, who deserves to end his career as Champion.”

Schneider showed grace in defeat, he is, and always was, a class act. “Failing to win the title after 10 races by just 10 seconds shows how tough we raced for the Drivers’ Championship this season. Although Mark and I didn’t manage to win the Championship, I’m glad for the team. Congratulations to my old friend Klaus, who deserves to end his career as Champion.” Mark later reflected on the result in his excellent autobiography ‘Aussie Grit’. “So, the end result was second place in the FIA GT Championship by a margin of eight points. My disappointment was tempered by happiness for Klaus, since that was his last year in racing, but I also felt it had been a little unfair on Bernd. His partner came from Formula Ford and F3, whereas Ricardo arrived as the new F3000 champion to partner Klaus and was already getting test drives in Formula 1. I could go toe-to-toe with them most times but sometimes I struggled, partly because it was Bernd’s car, basically, and he had it set up as he wanted it, and partly through sheer lack of experience.”

Mark later reflected on the result in his excellent autobiography ‘Aussie Grit’. “So, the end result was second place in the FIA GT Championship by a margin of eight points. My disappointment was tempered by happiness for Klaus, since that was his last year in racing, but I also felt it had been a little unfair on Bernd. His partner came from Formula Ford and F3, whereas Ricardo arrived as the new F3000 champion to partner Klaus and was already getting test drives in Formula 1. I could go toe-to-toe with them most times but sometimes I struggled, partly because it was Bernd’s car, basically, and he had it set up as he wanted it, and partly through sheer lack of experience.”  Zonta had this to say after the race. “This was a real tough title fight. I had to give it my all to keep the gap to Mark Webber wide enough to make it. The fact that we both went off because of oil on the track shows how close to the limit we were. I’m really happy about the title and that I could win it together with Klaus.”

Zonta had this to say after the race. “This was a real tough title fight. I had to give it my all to keep the gap to Mark Webber wide enough to make it. The fact that we both went off because of oil on the track shows how close to the limit we were. I’m really happy about the title and that I could win it together with Klaus.” The retiring Champion had the last word. “I’m extremely happy about the Championship. This was a sensational achievement by the team, and my co-driver Ricardo is the best I could have asked for. I want to thank especially Norbert Haug and Hans Werner Aufrecht, who brought me back to AMG Mercedes.”

The retiring Champion had the last word. “I’m extremely happy about the Championship. This was a sensational achievement by the team, and my co-driver Ricardo is the best I could have asked for. I want to thank especially Norbert Haug and Hans Werner Aufrecht, who brought me back to AMG Mercedes.”